Many children who attend school have or will experience some type of trauma that may affect cognition, behavior, and relationships (Van Der Kolk, 2014). According to the National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN, 2016), difficulties that accompany trauma can also include poor social skills, increased aggression, an inability to trust, dysregulation, fearfulness, anxiety, and avoidant behaviors. What can we do to help support these students in regaining trust and decreasing anxiety? Rather than trying to normalize what they're going through, we should educate them in self-awareness.

Portraits of Student Trauma

The school we work in, Beijing Haidian Opportunity School, is the first alternative school in China and has been in operation for 65 years. Our school mainly accepts students who were expelled from ordinary primary or middle schools, those with mental and behavioral disorders, learning difficulties, and those who have committed minor crimes. Many students have suffered various childhood traumas such as emotional and physical neglect, natural disasters, or school and community violence. Wang, a 7th grade student at our school, has experienced family violence since birth. He is very active in class and often disrupts sessions and destroys classroom materials. At the same time, he has a serious tendency toward violence and easily fights with others. Zhang, Wang's classmate, has long lacked the care of his parents. He is silent and does not like to talk. In the classroom and on the playground, he has a hard time initiating play with peers and shows indifference to the people and affairs around him.

Like many children who have experienced traumatic events, Wang and Zhang view the world as a dangerous place and are more vulnerable to stress, which can sabotage their ability to manage emotions and use coping mechanisms that can help to regulate their behavior. When children live in a constant state of fear and are not supported in the regulation of their emotions, they can become highly impulsive (Herman, 2018). Experiencing trauma in early years can create a highly reactive stress response that is difficult to control when there is a perceived threat. Chronic stress or fear raises cortisol and adrenaline hormone levels in young children, which can cause them to be constantly on guard and makes them vulnerable to anxiety, panic, hypervigilance, and an increased heart rate (Katie Statman-Weil, 2015). Wang and Zhang have different personalities, but they have something in common: they are often frustrated with their lives, which affects how they behave in class.

Supporting Students with Nonviolent Communication

In trauma-sensitive spaces, teachers can support children by creating positive self-identities (SAMHSA, 2014). To make classroom environments ripe for communication, we have found nonviolent communication very effective. This includes clear, empathic communication, consisting of four areas of focus: observations, feelings, needs, and requests.

Observations: The facts (what we are seeing, hearing, or touching) are distinct from our evaluation of their meaning and significance. When teachers combine observation with evaluation, students are apt to hear criticism and resist what teachers are saying. Instead, a focus on observations specific to time and context is recommended. When the teacher observes Wang's playfulness in class, he should not directly point out what he is doing. He should instead observe and evaluate the overall situation of the entire class and remind particular students to stop playing with toys without directly pointing them out. Instead of saying, "Wang, stop playing your toys. Why don't you ever listen well?", try saying, "I see some students listening and some being off task …"

Feelings: Feelings reflect whether we are experiencing our needs as met or unmet. Identifying each other's feelings allows us to more easily connect. If teachers point out students' problems directly, those students may feel uncomfortable and exhibit rebellious behavior. Teachers can instead encourage students who are performing well. Instead of saying, "Some students are deliberately acting against the teacher. Standing in a neat line is basic behavior!", consider saying, "I have observed that some students are standing in line. Maybe others should learn from them …"

Needs: It is posited that "Everything we do is in service of our needs." When Zhang does not want to participate in other students' activities, the teacher can take the initiative to ask him if he has any needs, or offer him some help, so that he feels cared for. Instead of saying, "Zhang, don't be in the corner by yourself. Go join the activities!", consider saying, "I see you are not playing with other students. Do you need any help?"

Requests: Instead of demands, which are often triggering as an attempt to force the matter, a request empathizes with what is preventing the student from saying "yes," before deciding how to continue the conversation. It is recommended that requests use clear, positive, concrete action. Instead of saying, "I suggest you all take part in the spring outing organized this weekend, it will be very interesting!", consider saying, "We want to organize a spring outing this weekend. If anyone doesn't want to go or has a better idea, please let me know!"

Methods of Support

Though we recognize teachers are not licensed therapists, there are ways schools can support students with special activities. Especially in those cases where therapists may not be available. Our school has developed a handbook and training at the beginning of each semester for all teachers, written by our school's psychological counselors. The handbook includes instructions on how to communicate with students and how to observe and understood students' emotions. Counselors receive feedback from the teachers every week to help them solve problems they encounter in the implementation process.

Based on Martin Seligman's work around increasing happiness using six virtues and 24 strengths (Seligman et al, 2005), we have summed up 52 Positive Quality Words (PQW) that meet the development needs of students. In order to instill these qualities in students' minds, we have activities that encourage happiness, well-being, and positivity.

Mood Weather Report: Learn More About Your Students

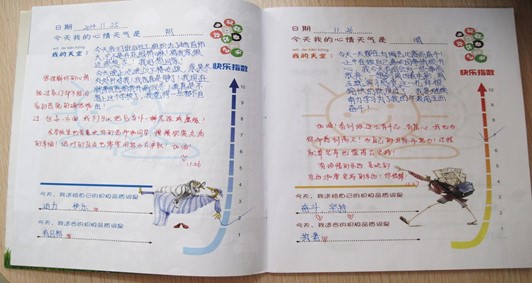

Childhood trauma survivors are more likely to feel insecure about their surroundings. Therefore, it is important to record their daily psychological state. To build up confidence and face life every day actively, our school asks students to record their "Mood Weather Report" every day.

The content of the report includes five parts: Mood report (comparing their mood to a certain weather state, e.g., sunny, windy, cloudy etc.); Colorful sky (describing the events of the day); Happiness index assessment (a score from 1–10), positive quality words (PQW) describing their day, and PQW describing their ideal future self. To encourage students to establish positive emotions, they should be aware of their feelings and behaviors from a positive perspective and affirm their positive psychological qualities.

The mood weather report has two specific versions: "Happiness version for middle school students" and "Happiness version for high school students." According to the "PQW describing my day" and the "PQW describing my ideal future self," students refine and recognize their positive psychological states for one day. If students' writing is not comprehensive enough, teachers will further refine according to the specific events and feelings students describe and reply with PQW to everyone's mood report, recognizing students are heard.

Figure 1. Positive Quality Words and Mood Weather Report

| Positive Quality Words | Mood Weather Report |

|---|

| Basic Level | Curiosity: Being open to new experiences Love to study: The desire for knowledge Creativity: Solving problems in different ways Love to think: Ask why to everything | Date:_____ Today, my mood weather is:______________________ What happened in my sky:______________________ Positive quality words describing my day:______________________ Positive quality words describing my ideal future self:______________________ Happiness index assessment (1-10):______________________ |

| Advanced Level | Bravery: Face your fears and move forward Perseverance: Persist in and achieve goals Honesty: Not lying, being honest with yourself and others. Integrity: Daring to act and take responsibility. | |

| High Level | Generosity: Being willing to share with others Fraternity: Getting along well with others and helping each other Politeness: Respecting others and being good at listening Gentleness: Being warm and kind in character | |

As students write their mood weather reports every day, teachers and psychological consultants pay attention to: 1) How they communicate with students and guide any general negative psychological emotions when first discovered; 2) If students have serious psychological confusion, psychological teachers offer individual training courses, generally 3–10 class hours; 3) For students with particularly serious psychological problems, the school sets up growth support groups. Psychological teachers, together with class teachers, psychological counselors, parents, social workers, and peers, provide positive psychological support in the form of growth support communities and hold case assessment meetings regularly to diagnose and implement correction.

Last year, Zhang wrote the weather of his day as "cloudy" for a week and didn't want write any positive quality words. When the teacher asked him why, he said his parents scolded him almost every day because he had broken his fathers' motorbike. The teacher comforted him and contacted his parents for a conversation about how he was struggling and how they could all support him.

Sandplay Therapy: Understanding Growth

We also encourage students who have experienced trauma to carry out sandplay activities. Sandplay has two main purposes in order to observe the changes of students' mental processes: to understand students' current psychological states and to detect possible psychological anxiety problems also found in their daily MWR. This is also a way to observe students' psychological growth over a period of time (e.g., a semester).

The students are free to choose which toys to incorporate into the tray and arrange them in any way that they want. The teachers and therapist mainly serve as observers and rarely interrupt. It is thought that the students are able to create a world that represents their internal struggles or conflicts. After sandplay, the teachers and students often discuss what students created: why they chose specific toys and their arrangement, any symbolic or metaphorical meanings, and a name for their completed sandplay.

Zhang made seven sandplays, including the one pictured above, with names like "Deserted Island," "Isolated Concert," "Night Communication," and "I Wish." Because we tracked sandplay over time, we witnessed Zhang's internal growth from inner inferiority to finding his own strengths, from inner loneliness to being able to communicate with others with an open attitude, from inner resistance to tolerance and acceptance of himself and others, illustrated by what he chose to capture in his sand play.

A Plan for Improvement

What matters most in developing positive and supportive learning environments that are responsive to the needs of students who have been affected by trauma is offering them unconditional love, support, and encouragement. Schools who wish to do the above should establish an effective Nonviolent Communication mechanism first, observe the psychological states of students in a timely manner, and have them better communicate with peers and teachers through interactive activities that allow them to find a more positive way of daily life and a more hopeful future.