As Jean Robillard drives through the midday traffic, her thoughts are on a recently vacated downtown store. After operating it for two decades, the owner liquidated his inventory and closed the business. Now the community must decide which new business will occupy this choice location across from the town square.

Robillard is neither a member of the town planning department nor a real estate developer. She is vice president of a merchandising firm who is on her way to a 2nd grade classroom. As a volunteer consultant for the Junior Achievement Elementary School Program, she is teaching these youngsters about the economics of the local community. Jean is one of 12 volunteers, each of whom is presenting a grade-level theme to a class at Jones Elementary. Accompanying her today is Ralph Garcia, a marketing executive, who is teaching the "Our World" theme to 6th grade students.

Jean and Ralph are eager to discover how the students will respond to the day's activities. Jean is teaching about jobs, work, productivity, and the role of government, along with other economics and business concepts. Today promises to be particularly interesting for her, because the children will consider the problem of which new business to locate in the vacant store. Down the hall, Ralph's class will engage in foreign trade and currency exchange.

Launching the Program

Providing an economics and business education curriculum to elementary school students is not a new endeavor for Junior Achievement. Students in the upper elementary grades have taken part in our Business Basics program since 1978. Junior Achievement introduced the Elementary School Program in 1992. The new program was an ambitious one. It featured sequentially integrated themes for kindergarten through 6th grade. Schools across the nation received the program enthusiastically; by the 1994-95 school year, more than one million elementary school students were participating.

The Theme. Jean Robillard's class is working on the "Our Community" theme. Used largely in 2nd grade classrooms, it is one of seven themes in the Elementary School Program (see fig. 1). Each theme helps students to understand how they can contribute to society as workers, citizens, and consumers.

Figure 1. Elementary School Program Themes

Starting Early: Junior Achievement's Elementary School Program - table

| Kindergarten | "Ourselves" |

| Grade 1 | "Our Families" |

| Grade 2 | "Our Community" |

| Grade 3 | "Our City" |

| Grade 4 | "Our Region" |

| Grade 5 | "Our Nation" |

| Grade 6 | "Our World" |

The Consultant. The business volunteer—called a consultant—presents the learning activities. These activities are hands-on—students often work in teams to develop communication skills, apply concepts, and assume leadership roles. Local Junior Achievement staff members who have been trained at the National Headquarters in Colorado Springs, Colorado, are responsible for training the consultants.

The Consultant-Teacher Team. Each consultant is encouraged to visit the class before presenting his or her first lesson. This gives the consultant a chance to meet the students and tell them a little about what they will be doing during subsequent visits. In turn, the teacher (who may be seeing the consultant and working with the program for the first time) can prepare the students for the program.

Judith Lee Swets, a 2nd grade teacher at Hall Elementary School in Grand Rapids, Michigan, recalls her introduction to the Elementary School Program: A few weeks after learning that the Junior Achievement program would be in my class, Theresa King, my consultant-to-be, introduced herself to the students and me. She was pleasant, soft-spoken, and well mannered. "Whoa," I thought, "these kids aren't going to listen to her." But I was wrong. Before the first lesson, I prepped the kids: We went over the rules about being courteous and polite, and I promised them a reward if they made me proud. Theresa started the lessons by talking about her job; I could see some students becoming restless. Then she pulled out a large, colorful drawing of a community and placed it on the wall, and the students became intrigued. She gave the children their own copies of the drawing, and they became more interested and curious. After receiving colored stickers showing different people and jobs, they were hooked and ready to participate.

The Evaluation Plan

The same year Junior Achievement introduced its curriculum, it also commissioned the Western Institute for Research and Evaluation, in partnership with Utah State University, to develop a three-phase evaluation plan. This ongoing evaluation includes formative, summative, and longitudinal studies. Students, teachers, parents, school administrators, volunteers, and Junior Achievement staff members comprise the study's multiple sources, or stakeholders. Data collection methods include stakeholder surveys, objective-referenced tests, classroom observations, individual and focus group interviews, and alternative assessments (direct assessments of students' performance). Our study will extend through the 1998-99 school year, so we can examine the cumulative impact of the program on a group of students as they progress from 1st through 6th grade.

The Formative Study. During the first year of the evaluation, our team worked to identify problems with the program. We surveyed teachers, principals, consultants, students, and parents, and found they valued the real-life applications of the program. We discovered that the curriculum was appropriate for urban and suburban children, for both genders, and for a diverse array of ethnic groups.

We also discovered that the consultants needed better training and the teachers needed to be involved in that training. For example, consultants wanted help on classroom management, and teachers asked for ways to integrate the program into the general curriculum. In addition, we learned that certain activities in some themes needed a clearer focus.

We continued to gather implementation data during the 1993-94 school year. We found that nearly half the consultants surveyed went beyond the five core activities and made more than six classroom visits. Both teachers and consultants said they wanted more activities. Several recommendations resulted from this formative phase of the evaluation (see fig. 2).

Figure 2. Formative Evaluation Recommendations

Establish a school liaison to facilitate communication among the teachers, consultants, and Junior Achievement staff.

Encourage consultants to make an observation visit before presenting the first activity to a class.

Emphasize effective classroom management and instructional practices in consultant training sessions.

Encourage teachers to take a more active role in supporting the consultant.

Recognize the efforts of consultants and the support of their immediate supervisors.

Summative Findings. During the 1993-94 school year, we also began to gather data on the program's impact on student achievement. To get information from a large number of program sites and to generate in-depth information from selected sites, we divided Junior Achievement areas across the nation into two tiers.

Tier 1 sites were chosen from cities that had piloted the program during 1992-93. Thirty-six cities participated at this level. Volunteer consultants and teachers in these cities completed survey instruments.

Six cities were selected to participate as Tier 2 sites. These sites qualified for the comprehensive evaluation because their programs operated at every grade level and in every classroom. Each of these sites also included a substantial at-risk student population. And collectively, they provided an ethnically, geographically, and socioeconomically diverse student population. The Tier 2 assessment included surveys of key stakeholder groups, on-site visits by the evaluation team to administer student tests and attitude scales, and interviews with stakeholders.

We compared our findings from the project schools, which used the Junior Achievement program in the whole school, with findings from control schools. These schools had not implemented the Elementary School Program, but were comparable to the project schools in other ways (for example, socioeconomic status and ethnicity of students, test performance, and type and size of school).

During the first year of the summative study, we conducted interviews with local Junior Achievement staff members, four to six teachers, three to five consultants, and the school principal at each site. We administered objective-referenced tests to all classes, grades 1-6, at each project school, and in two classes at each grade in each control school. We held focus groups for consultants and teachers at three sites. And, we asked students and teachers in the project and control schools to complete attitude surveys.

Because we found no existing instruments that measured concepts and skills comparable to those included in Junior Achievement's theme, we developed, piloted, and validated a separate test for each grade level. These tests ranged from 17 items for the 1st grade "Our Families" theme to 36 items for the 5th grade "Our Nation" program. A total of 3,820 students from project and control schools took part in the study. More than 3,200 students in the project schools also completed attitude surveys.

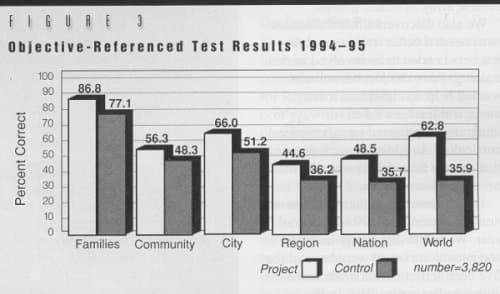

During the first year of summative evaluation, we found that the Elementary School Program was having a significant impact on students. Our evaluation during the 1994-95 school year reinforced these findings (see fig. 3). At each grade level, the difference in students' scores was both statistically significant and educationally meaningful.

Figure 3. Objective-Referenced Test Results 1994–95

The Longitudinal Study. Last year, we extended the summative evaluation to look at the long-term effects of the program. At the same time, we expanded our data collection methods to include alternative assessment. We identified 2nd grade students at each Tier 2 site who were participating in "Our Community" and who had completed "Our Families" the previous year. Across the six sites, 251 youngsters became part of this third phase of the study. We will track the achievement of these students during the years they participate in the program.

We tailored the exercises developed for the alternative assessment to help students synthesize their knowledge, apply it to solve problems, and think critically about economic concepts. (For example, in one exercise, 3rd graders worked in groups of five to plan a city by placing buildings, parks, and homes within zoning sites.) The assessment at each grade level from 2 through 5 consisted of two or three such exercises. We used only one, more complex, exercise for the 6th grade assessment. We did not develop alternative assessment items for 1st grade students because most children at this age cannot understand the conceptual distinctions necessary to carry out such activities.

Results of the alternative assessment show that students who participate in the Elementary School Program are not only learning concepts and skills, but they also are learning how to apply them to new situations. We know the project school students are much more effective at performing tasks that demonstrate understanding of economic principles than are students who are not participating in the program.

For example, Junior Achievement students were quite adept at creating and analyzing assembly line production methods (Activity 1, "Our Community") and designing a city using a zoning map (Activity 1, "Our City"). They also demonstrated excellent knowledge and skills in "applying for a job," and showed that they understood the principles of "operating a business" better than did students not participating in the program (Activities 1 and 2, "Our Nation").

The largest difference between the project and control groups occurred with the "Our World" theme. Junior Achievement students demonstrated that they were better able to manipulate multiple currencies and understand the basic principles of exchange and global trade than were their nonparticipating peers.

A closer look at the alternative assessment, however, indicated that participating students in the lower grades exhibited essentially the same ability to think critically about problems as the control group students did. For example, we asked 2nd graders to generate multiple solutions to a problem and list the advantages and disadvantages of each solution. Although this was similar to an activity in "Our Community," their ability to carry out the exercise was not significantly better than that of their counterparts in the control classrooms.

Using the Evaluation Data

The curriculum department at Junior Achievement's National Office has used our findings to build a higher-quality program. For example, many sites have established a school liaison (generally a teacher or principal) to facilitate communication among local Junior Achievement staff members, teachers, and consultants.

As a result of the summative study, evaluators were able to identify weaker activities—those that did not help students grasp the content or develop the desired thinking skills. For example, in the "Our City" theme, each activity was reinforced to illustrate the relevance of education to the careers that people pursue. Virtually every activity in each grade-level theme was modified, if only minimally, to enhance its effectiveness. And the curriculum staff developed additional activities for each theme. In addition, consultants are receiving more intensive training with those activities designed to foster problem-solving skills.

Back at the Office

As they return to work after their classes at Jones Elementary, Jean Robillard and Ralph Garcia are still excited about the day's events. Ralph is impressed with the enthusiasm of the students and the facility with which they imported and exported goods using different national currencies. Jean reflects on the ideas that her 2nd graders developed in response to the issue they faced.

Their efforts are particularly rewarding for Ralph and Jean because the Jones students are an ethnically diverse group. They come from families that are hard working but of modest means. As a group, these students do not display high levels of academic achievement. Yet, the students appear to thrive on the challenging array of activities presented. And, as evaluation helps to shape and sharpen the focus of this curriculum, there is every reason to believe that it will be even more effective in the future.