At Franklin, Seattle's oldest high school, the annual "Preach" is always a big deal for students—and for me. Preach is slang for the end-of-year summative oral presentation, or speech. During my 14 years at Franklin teaching history, government, and American literature, I've seen how a civics and political science perspective ignites enthusiasm in all students.

Although I consider myself a semi-tough old coach, I typically need to bring a few tissues to the Preach because it's so powerful. Each June, after their final exams, my scholars take to the PreachBox (the podium) and give a formal speech that answers the question that shaped the year: What are your political views and conception of civic duty, and how have they evolved this year in response to what you've learned? Most students say that they had initially either hated or ignored politics but that the course's relentless connection of past to present got them interested. Students typically report a dramatic increase in their desire and ability to make the world a better place.

Last spring, as always, the presentations were scholarly and touching. Hannah's and Ralayzia's were particularly memorable. Hannah is one of the few white kids in the school (93 percent are students of color, and 72 percent qualify for free and reduced-price lunch). With poise, erudition, and a clearly drawn rhetorical plan, she argued powerfully for a rebirth of the Progressive Era's culture of political activism. She drew connections between Upton Sinclair's book The Jungle—which describes the tainted food, unspeakable working conditions, and corruption in Chicago's meatpacking industry during the Gilded Age—and issues facing our food industry today. She praised Teddy Roosevelt's creation of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration as well as his bold conservation measures, and she made a public commitment to intensify her civic engagement in environmental issues.

Ralayzia's speech blew the class away. Her explanation of the historical domestic and foreign policy battles that had spoken to her during the year was magisterial, like listening to the doctoral defense of a political science PhD candidate at Johns Hopkins University. The way she interwove history's lessons with the words of Abraham Lincoln and Ralph Waldo Emerson and her intense civic courage and passion for social change were stunning. When she finished, the cheering, hooting, and applause were like magic, as was the look of pride on her face.

My students know they're special—and that their voices matter. The curriculum design tells them this every day. Students relish the opportunity to "preach their game" with authenticity, honor, and sophistication. They believe it's their civic duty to share their opinions and their growing wisdom with the community. This belief is nurtured and cultivated from day one when students are handed Emerson's "Self-Reliance" and are asked to accept his invitation to "trust thyself" and speak with "words as hard as cannonballs." Few adolescents can reject this invitation.

Franklin graduates move on to all walks of life and leave the school with self-confidence and a fiery sense of civic duty. Students give back to their communities in crucial ways—like Leana, who now works at a local youth counseling agency; Veratta, who runs a shelter for homeless women as she finishes up her master of education degree; and Zenriquez, who works at Panasonic and volunteers at Franklin as a mentor and coach.

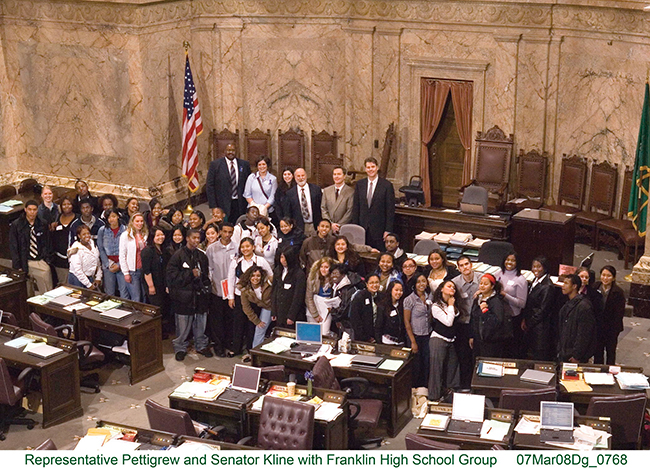

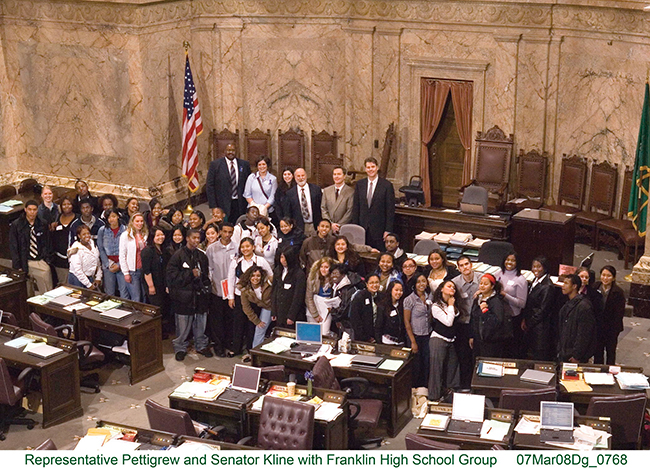

Photo courtesy of Audra Rutherford

The Threats to Civics Education

Whether students go straight into the work world or earn the title of college graduate, all students must be groomed for the most honorable title in the land—that of citizen. However, according to former Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O'Connor, America has a "crisis on our hands when it comes to civics education" (Dillon, 2011, p. A23). Her alarm was prompted by the 75 percent of teens who failed the 2010 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) civics test.

Standards-based education seems to be civics-bereft education. The teach-to-the-test imperatives of No Child Left Behind, Race to the Top, and the common core state standards dominate our schools. According to Ted McConnell, who works with O'Connor as the executive director of the Campaign for the Civic Mission of Schools, "We're failing to educate the next generation in civic knowledge, civic skills, and the disposition to participate [because] kids are being drilled to death in math and reading" (quoted in Resmovits, 2011). The words civic and civics don't appear in any of the common core state standards that have been adopted in 45 U.S. states.

The crisis in civics education is a reflection of the profound economic, social, political, and spiritual malaise that our nation and our children are enduring. With 1.3 million students dropping out of school each year (Wingert, 2010) and adolescent suicide rates on the rise (Baker, 2007), a substantial proportion of our young people seem to be grappling with a meaninglessness and hopelessness in their lives.

This is our society's greatest moral problem, but it's also an opportunity—because meaning and hope are just a lesson plan away.

The Benefits of a Civics-Infused Curriculum

Harvard professor Michael Sandel, famous for his "Justice" course and 2009 book, suggests that a robust civics curriculum can help bring "moral clarity to the alternatives we confront as democratic citizens" (p. 19). Whether it's the study of tax policies in math class, burqa laws in French class, or global warming in science class, raising moral and ethical questions by teaching civics across the curriculum offers several benefits.

First, students experience increased relevancy in subjects in which they struggle. For example, civics connections in math and science classes often leverage student interest in current events, such as the March 2011 tsunami and nuclear catastrophe in Japan. Second, it reduces the likelihood that students will drop out; 83 percent of at-risk students surveyed said that service learning made it less likely that they would drop out of school (Bridgeland, DiIulio, & Morison, 2006). Third, research has shown that teaching civics across the curriculum results in gains in cognitive achievement, student effort and attention, and the amount of homework completed (Billig & Klute, 2003). Finally, such an approach creates a common instructional language and experience among all departments and classrooms. Both teachers and students benefit from the increased interdisciplinary connections.

In the Classroom …

Last spring, many of my students lobbied district leaders to give all high school students in Seattle a civics-rich curriculum experience like theirs. Their idealism inspired me to create the Civics for All model (see www.civicsforall.org). Before a packed school board audience, past and present students attested to the value of the initiative, which proposes the integration of civics-based lessons across all K–12 classrooms and academic disciplines in Seattle public schools. Zenriquez, a 2003 graduate of Franklin's public service and political science academy, testified that the civics education he received there "changed my life and could arguably change the lives of hundreds of kids around this city." All students thrive when political analysis of current events helps them understand the relevance of history and literature to their lives, their country, and their world. In the Civics for All model, students are called on to debate such questions as, What is the common good? How do governments get and keep legitimacy? Do citizens have a duty to actively participate in their government? Students frame their responses to these essential questions through an ongoing review of the old-fashioned political spectrum, a continuum that spans from right-wing reactionary to conservative to moderate to liberal to left-wing radical. Kids love using the framework to understand issues because their mastery deepens with each year's study of the philosophical and theoretical roots of conservatism and liberalism; they learn how to classify a variety of topics—whether in history, literature, or current affairs—on the spectrum.

For example, on one end of the spectrum, they might compare the Occupy Wall Street movement with social unrest in the 1960s. Moving to the other side, they might trace the roots of fascism all the way back to ancient Rome through Nazi Germany and hear its echo in the immigration policies of some European countries today. Students are eager to spar on the issues, arguing about whether they agree with a given policy direction (like the Vietnam War) or the political angle of an author (like Tim O'Brien's book about that war, The Things They Carried [Houghton Mifflin, 1990]). Finally, students are expected to illuminate personal connections between the timeless issues of the past and present.

Photo courtesy of Brandon Watts

And at the Legislature

The political spectrum frames the engaging and challenging annual Olympia Project. This four-week service learning project in February requires juniors to research the annual crop of bills on the state legislature's website; find bills of personal interest; track those bills; lobby the community to support or oppose the bills; testify in a mock legislative committee hearing in front of distinguished citizens (including parents); and finally, journey to the state capitol in Olympia to lobby for their bills. Students can spread the word about the cause they're championing or challenging by creating YouTube videos and using social media, such as Facebook, Twitter, and blogs.

Ever-recurrent issues—such as the death penalty, abortion, and gun control—are always discussed, as are bills that speak to students on a personal level. For instance, last year one of my pupils, Justin, who regularly places in local salmon fishing tournaments, lobbied his legislators on a fisheries preservation bill. For his senior project, he waded into the congressional war over the Pebble Mine, the proposed largest open-pit mine in North America. Why? Because the mine would be in the headwaters of Alaska's Bristol Bay, home to the world's greatest remaining salmon fishery.

Before going to Olympia, all students are required to amass at least 300 signatures to submit to a legislator. Students compete to get the most signatures and make the hottest Olympia flyers, which they post around school and the neighborhood. Clipboard in hand, they go about the business of being a citizen and engaging others in that business. As students advocate for or against their bills around the community, they actively teach their fellow citizens not only about current political issues, but also about the political process itself. From school hallways to basketball games, from the corner store to their places of worship, students are expected to "preach" the merits of their position.

In 2007, my students helped pass SB 5098, a guaranteed low-income scholarship program. The students became such experts on the various provisions of the bill, including tax policies and scholarship funding formulas, that the state Higher Education Coordinating Board spent 90 minutes reviewing the bill with 60 student "experts." The students convinced the board to increase the grade point average eligibility requirement from 2.0 to 2.5 because they thought a 2.0 was "a handout." The bill, with its revised minimum grade point average requirement, passed into law, and many of their siblings, relatives, and neighbors are enjoying the benefits of this program right now.

Or consider what my juniors took on last spring, when Congress moved to slash Franklin's federal Learn and Serve outreach coordinator position. They wrote letters, sent tweets and e-mails, and gathered more than 3,000 petition signatures to send to President Obama to save the position. They produced this blizzard of political action in less than a week.

Federal- and state-level service learning activities like these build bridges between students and their elected representatives—a win-win situation for everyone involved. Over the years, I've had classroom visits from school board members, state representatives and senators, the League of Women Voters, and education policymakers from the state capitol. The best way to build bridges to the outside world is to give your students the skills and guidance to invite outsiders to your classroom or school.

A Bold Proposition

Civics education is everyone's responsibility and everyone's opportunity for growth and gratification. Nevertheless, infusing a K–12 civics lens into all classrooms is a bold proposition that will require a major retooling of the standards movement and some focused teacher professional development—and, especially, the will to make it happen.

Like all change, such an approach will encounter resistance. Educators should recall the legacy of Louis Brandeis, the first Jewish Supreme Court justice. In a 1927 decision, Whitney v. California, Brandeis wrote that "the processes of education" require "more speech, not enforced silence" and that our country's founders knew that "public discussion is a political duty."

So let's engage in that discussion and let our students' voices be heard.