Sometimes, when you're handed a new, many-sided responsibility, it's all about finding the right balance. I'm superintendent of the Durand School District in Durand, Michigan. As is true in many U.S. states, thanks to new legislation, Michigan's school leaders now face increased responsibility for evaluating teachers, making decisions about staffing and tenure, and demonstrating student growth.

In Durand, a rural district with four schools that serve 1,650 students, we chose to see this legislation as an opportunity to break free of old norms. We aimed to create a process that would promote real professional growth among teachers—as opposed to carrying out a compliance model based on a few mandatory observations. In working to develop a process for more intensive teacher evaluation, we discovered three important balancing acts school leaders must perform. Allow me to share some of our insights and the ways we're rising to this challenge.

Balancing Simplicity and Depth

The first challenge we faced was finding the right mix of simplicity and depth. As we researched various teacher effectiveness frameworks, we found that many were comprehensive but overwhelmingly complex, with countless rubrics and performance levels. A cumbersome instrument isn't practical in a principal's world, especially when many principals must wear multiple hats because their budgets are shrinking. So this level of complexity worried my district—and we aren't the only worried ones. A report by the Measures of Effective Teaching Project (Kane & Staiger, 2012) warned that "when observers are overtaxed by the cognitive load of tracking many different competencies at once, their powers of discernment could decline" (p. 28).

Durand wanted a framework that would allow administrators to conduct observations without becoming overtaxed, collect formative data over time to build a realistic picture of teachers' levels of expertise, and give teachers immediate feedback on classroom practice. We selected the Thoughtful Classroom Teacher Effectiveness Framework created by education consultants Silver Strong and Associates (2012), believing that the visual organization of this framework—an overview of which can be represented on one page—would address our concerns about complexity.

This framework highlights central elements of effective instruction in a way that can help any school leader shape evaluation systems for simplicity and substance, whether or not the leader adapts the additional resources associated with the framework.

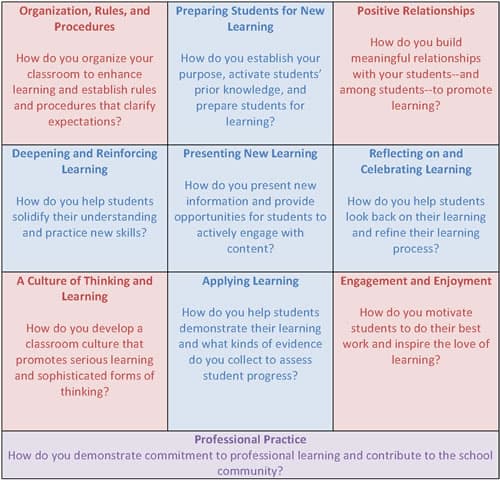

As Figure 1 shows, the framework posits four cornerstones of effective instruction (highlighted in pink). These are universal foundations of all successful classrooms. Whether a principal is observing a primary classroom or an advanced placement European history course, he or she wants to see organization, rules, and procedures; positive relationships; engagement and enjoyment; and a culture of thinking and learning. In Durand, we decided to evaluate teachers on all four of these elements.

Figure 1. The Thoughtful Classroom Teacher Effectiveness Framework

Source: The Thoughtful Classroom Teacher Effectiveness Framework by Silver Strong and Associates, Ho-Ho-Kus, NJ: Author. Copyright 2011 Silver Strong & Associates. Adapted with permission.

The framework also highlights (in purple) elements of teacher effectiveness beyond the classroom that evaluators should consider: the commitment to professionalism, to ongoing learning, and to the school community.

The five blue boxes in the center of the framework synthesize research and practice on instructional design into five broad steps that good teachers take in any extended learning sequence. They (1) prepare students for new learning; (2) present new information and help students acquire new learning; (3) help students deepen and reinforce what they've learned; (4) empower students to apply their learning in meaningful ways; and (5) encourage students to reflect on their learning and celebrate their achievements.

Good instruction unfolds in a series of such episodes. As administrators watch one class period, they may not observe all these episodes. They can greatly increase the effectiveness of their observation and the accuracy of their judgments if they know which of these five episodes the class is engaged in. If, for example, an observer recognizes that a teacher is beginning a new unit as opposed to allowing students to practice previously learned material (deepening and reinforcing new learning), both teacher and observer can be assured that the observer will focus on the relevant instructional practices. This puts observer and educator on the same page.

To help administrators move from the simple to the deep—from a commonly understood overview to a close assessment of a teacher's practice—the framework includes, for each of the five dimensions, an essential question and a set of teaching practices and student behaviors that guide observation of that dimension. For example, the essential question for Preparing Students for New Learning is "How does the teacher establish purpose, activate students' prior knowledge, and prepare students for learning?" The framework lists eight "instructional indicators" for this dimension, including

- Selecting relevant standards that are appropriate to the content and grade level.

- Unpacking standards and turning them into clear, measurable learning goals.

- Beginning lessons and units with engaging "hooks."

Our district's teachers receive training in these indicators, and principals use them to help identify observable teaching practices and student behaviors. Each dimension also includes a four-level rubric (novice, developing, proficient, and expert) so observers can turn data from formal observations into a meaningful evaluation score.

One benefit of any powerful framework for teacher effectiveness (of which the Thoughtful Classroom framework is just one) is that when faculty study it together, they develop a common understanding about good teaching. The essential questions driving each dimension of this framework have become the basis for a common language in Durand about teaching, learning, and how to improve both.

Balancing Formative and Summative Evaluation

The second balancing act—between formative observation and summative evaluation—highlights two distinct roles that administrators must play when it comes to enhancing teacher effectiveness. They are both an instructional coach who works with teachers to improve their practice and an evaluator who makes high-stakes decisions. We've found that developing protocols for our principals to use in observation helps achieve this balance. Our protocols are relatively easy to implement, but they yield good information about teaching and learning.

Using the Four Ps

We've adopted and refined two protocols to help our school leaders coach teachers: a procedure to generate high-quality feedback on teachers' practice that we call the Four Ps, and guidelines for pre- and post-observation discussions.

Whenever an administrator observes a classroom, he or she adheres to the Four Ps: (1) provide specific evidence that explains your observation notes; (2) praise teacher behaviors that positively affected student learning; (3) pose questions that encourage teachers to reflect on their decisions and the impact those decisions had on student learning; and (4) propose ideas to help the teacher improve. Principals not only use these Four Ps to give feedback after informal observations, but they also use them as they write formal evaluations. This process ensures that our written evaluations are more than simple summaries of what an administrator observed.

We encourage teachers to use the Four Ps in their learning clubs to help one another improve their instruction. Many teachers use this protocol in their classroom to give students better feedback on their work.

As part of our formal observation process, observers meet with the teacher in question both before and after each observation. Tenured teachers are formally observed once each year and nontenured teachers twice each year; the district also suggests that school leaders do up to three informal visits or brief walk-throughs each year for each teacher.

To help principals conduct better pre- and post-observation conferences, we provided our administrators cognitive coaching training (Costa & Garmston, 2002), which trains school leaders to help teachers expose their thinking, explore the implications of their classroom decisions, and refine their practice. We established a set of questions that administrators pose to teachers in pre- and post-observation conferences. For example, in the pre-observation conference, administrators ask five driving questions:

- Where are you (the teacher) in your overall learning sequence?

- What are the learning goals for the lesson I'll be observing?

- How will you assess student learning?

- What learning activities and instructional techniques will you use to achieve your learning goals?

- What questions do you have about the lesson? What do you want me to look for?

The fifth question not only invites teachers directly into the observation process, but it also helps them answer questions about their own practice that are often difficult to see without an outside perspective.

Other elements we've adopted to maintain our focus on a formative process that promotes improvement include a teacher self-assessment process and a professional growth plan, which teachers use to set individual goals and track their progress toward these goals.

Fitting in Observation

To address the other side of this balancing act, we've created an evaluation system that uses multiple measures of teacher effectiveness.

By setting up a reporting and weighting system for all schools in the district, we made it relatively easy for principals to build an evaluative score for each teacher by reviewing data from classroom observations (which count for 50 percent of the overall score); assessing the teacher's effectiveness beyond the classroom (15 percent); and factoring in student performance data as reflected in both standardized test results and local assessments (25 percent). Each teacher's professional growth plan counts for 10 percent of his or her overall score. Plans are not scored according to their quality or according to whether each goal is fulfilled; teachers receive the full score just for making a plan and setting professional goals. This ensures that teachers commit to developing a plan. It also empowers teachers by giving them more control over their evaluation results.

Combining all these weighted scores yields an overall score on a scale of 1–4. We provide merit-based pay rewards for those who have high student growth scores. We have been using this system for a year in Durand, and so far teachers have responded well to the process.

Balancing Evaluation and Common Core

The third balancing act involves how to align our work in teacher evaluation with that other challenging national initiative: Common Core State Standards. In Durand, we felt it was essential to view teacher evaluation and Common Core as united around the larger idea of teacher effectiveness, instead of splitting our attention in two directions.

The Thoughtful Classroom Teacher Effectiveness Framework helped in this regard. Its indicators are aligned to key themes of the Common Core, such as reading more rigorous texts and evaluating and using evidence. Beyond just aligning indicators, we wanted to be sure our evaluation system measured the specific ways in which our teachers were helping students meet the new standards. So we're currently building new local assessments around the Common Core standards (students' scores on these assessments now count as 25 percent of every teacher's overall rating).

For example, vocabulary is a crucial component in the standards, which recognize that students' academic success rests heavily on their ability to remember, understand, and communicate with key vocabulary. Three of the six anchor standards for English language arts deal directly with vocabulary. So we decided to deal directly with vocabulary as well. Our teachers developed pre- and post-tests measuring specific vocabulary terms that are essential for success in each discipline. We'll be using these pre- and post-tests to assess how well students are mastering essential vocabulary and how well our instruction is advancing students' understanding of that vocabulary.

We're also working to assess student growth in key thinking and literacy skills, such as the ability to read and comprehend rigorous texts and reflect on learning. Thus, our teacher evaluation system is helping make Common Core real for our teachers, compelling them to rethink long-standing practices and look for ways to help all students meet these new standards.

Durand's journey into measuring teacher effectiveness in a way that drives teacher growth has only begun. But we've found that schools can best prepare for this journey and increase their likelihood of success by attending to these crucial balancing acts.