Recently I was standing in an airport boarding line and a voice behind me said, "Ms. T, you may not remember me, but I want to say hello."

I've taught long enough that my former middle school students are well into adulthood. The girls are confident managers of complex lives. Their frames are no longer spindly. The boys' voices are deeper and more solid. I did not recognize the deep voice that spoke to me, nor the mature and attractive face from which the voice came. Its owner was well over six feet tall.

Once he told me his name, however, I could see the young adolescent I had taught in his eyes and his smile, and we had a conversation that was at once easy and troubling. We talked about the middle grade years we shared, about his parents, and about his own family. And then I asked him what he was doing these days.

His eyes went to the floor, then back to me, then back to the floor. "This might surprise you," he said, "but until very recently, I was a teacher." He explained that he'd studied engineering in college, but found his post-college work as an engineer to be less than engaging. It was too repetitive for him and too detached from people, and so he got a job as a science teacher.

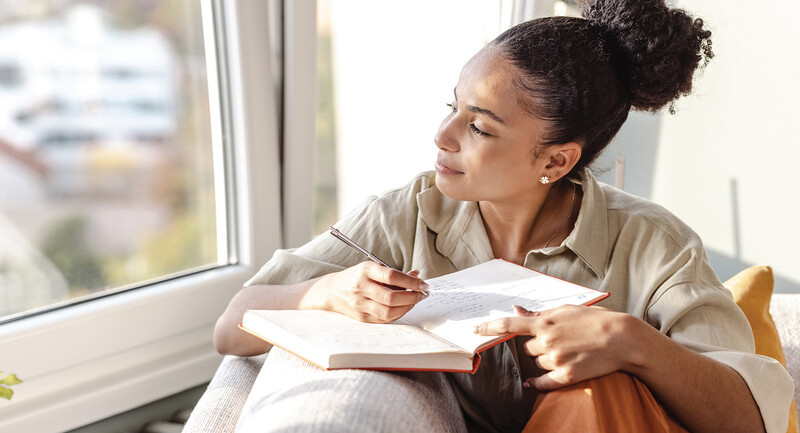

"I got up every day with a purpose," he said. "I loved that job." And then he paused and reconsidered. "I loved working with the kids. I wanted to make a difference, and I could see clearly that I was making a difference to them."

He stopped teaching, however, he said, because he sadly came to understand that teaching was a "dead-end street." My mind tried to process what "dead-end street" might mean—particularly to a young man who clearly loved his years as a teacher. I wondered about the salary, working conditions in his school, the demands of a teaching day—but before I could draw a conclusion, he explained it to me.

"There was no room for creativity in my work," he said, "really, almost none." He had little say in what he taught, and even in how he taught. "Everything was about covering information that might bulk up my students' test scores," he said.

He had wanted to show them the wonder of science, why it matters. But that wasn't an option. He began to feel robotic in his work. He could sense his own ingenuity diminishing and, worse, he could see his students losing touch with their creativity. He looked for ways he could influence the system and reverse the trends he saw all around him. But finally, he concluded that the system would bend and break him before he could bend it.

He is now working for an engineering firm again, and he still longs to make a difference.

Promises to Make—and Keep

I've thought about that conversation many times over the past few months. I wish I could say to my former student, and to all beginning teachers, "This job you're about to sign up for is really tough. It will require your best energies. Most days, it will require more than you have to give. That's OK, though, because there is no more significant work than shaping the minds and attitudes of young people. And you'll find schools to be places that nurture and support you in the work of helping young people discover and realize their promise."

In actuality, my former student drew a conclusion that has the ring of reality to too many promising teachers. Many of them work in places where there are too many students, too few resources, and salaries that are threateningly low. Some learn to live with those realities. Some do not. My student was taxed but not dissuaded by those conditions. What extinguished the light in him was a second, and arguably more crushing, reality: the pressure to raise student test scores.

In his school, curriculum and learning became highly prescribed, essentially meaningless, and devoid of joy. Dictated schedules no longer contained time for teachers to collaborate with students or colleagues, for students to play or talk with peers, or for teacher planning and reflection. Mandates were handed down almost daily that seemed designed to make more and more of the day "teacher proof." In the end, my engineering friend found it less painful to return to a job that seemed repetitive and "flat" than to continue in one that was extinguishing his creativity, personhood, and humanity—and that had a similar impact on the students in his care.

I'd like to believe—need to believe—that governments and schools would understand the meaning of the shrinking teacher pipeline and the stunning exodus of new teachers from the profession, and would do something about it. I'd like to believe—need to believe—that increasingly, the following promises to teachers could come to define and typify our schools:

- We will value the work you do in ways that reflect our awareness of its true worth.

- We will do all we can to ensure that schools have visionary leaders and that those leaders want to remain in place for the time necessary to cultivate an excellent school experience for each student in their care.

- We will create school climates that foster growth, collaboration, and joy in teaching and learning.

- We will pay you at a level that dignifies the teaching profession, the art and science of teaching, and the young people you teach.

- We will not confuse education and compliance.

- We will never reduce your students to a test score or you to a checklist.

- We will consistently ask you to challenge the habits and patterns of your teaching and will always give you the kind of intelligent support you need to achieve quality practice.

- We will give you the kind of voice every professional should have, and we will listen to and amplify your voice so that parents, policymakers, and the broader community can learn with you and from you.

- We will always value and nurture your creativity and will expect you to use it to create better curriculum, more engaging instruction, and better solutions to the many problems inherent in teaching the young in a complex world.

- And we will do these things because we understand that our support of and investment in teachers directly bears on the quality of life of our young, future citizens, and society as a whole.

Can we not agree on these basic professional assurances? After all, repairing, or even replacing, a leaky teacher pipeline is far less expensive than the costs of continuing neglect.