A teacher's first year on the job is often difficult. According to research, student achievement tends to be significantly worse in the classrooms of first-year teachers before rising in teachers' second and third years (Rivkin, Hanushek, & Kain, 2005). The steep learning curve is hard not only on students, but also on the teachers themselves: 15 percent leave the profession and another 14 percent change schools after their first year, often as the result of feeling overwhelmed, ineffective, and unsupported (Ingersoll & Smith, 2003; Smith & Ingersoll, 2004).

Surveys and case studies offer compelling insights into the areas in which new teachers commonly struggle. By effectively addressing these areas, schools can help new teachers improve their skills more quickly, thereby keeping them in the profession and raising student achievement.

Struggling with Classroom Management

The biggest challenge that surfaces for new teachers is classroom management. A 2004 Public Agenda survey found that 85 percent of teachers believed "new teachers are particularly unprepared for dealing with behavior problems in their classrooms" (p. 3). A separate survey of 500 teachers found that teachers with three years or fewer on the job were more than twice as likely as teachers with more experience (19 percent versus 7 percent) to say that student behavior was a problem in their classrooms (Melnick & Meister, 2008).

When interviewed, many beginning teachers say their preservice programs did little to prepare them for the realities of classrooms, including dealing with unruly students. "A bigger bag of classroom management tricks would have been helpful," one first-year teacher confessed (Fry, 2007, p. 225).

New teachers universally report feeling particularly overwhelmed by the most difficult students. One Australian first-year teacher interviewed for a case study observed that having a disruptive "student in my classroom is having a significant impact on my interaction with the remainder of the class … As a first-year teacher, I don't have the professional skills to deal with this extreme behavior" (McCormack, Gore, & Thomas, 2006, p. 104). Often, classroom management difficulties can prompt new teachers to jettison many of the research-based instructional practices they learned in college (such as cooperative learning and project-based learning) in favor of a steady diet of lectures and textbooks (Hover & Yeager, 2004).

Burdened by Curricular Freedom

Another concern that new teachers commonly raise is a lack of guidance and resources for lesson and unit planning. In a recent survey of more than 8,000 Teach for America teachers nationwide, 41 percent said their schools or districts provided them with few or no instructional resources, such as lesson plans. When classroom materials were provided, they were seldom useful; just 15 percent of the respondents reported that materials were of sufficient quality for them to freely use (Mathews, 2011).

Although such curricular freedom may be welcomed by veteran teachers, it appears to be a burden for new teachers, who have not yet developed a robust repertoire of lesson ideas or knowledge of what will work in their classrooms (Fry, 2007). Case studies have observed novice teachers struggling "just trying to come up with enough curriculum" and spending 10 to 12 hours a day juggling lesson planning; grading: and the myriad demands of paperwork, committees, and extracurricular assignments (Fry, 2007, p. 225).

It's worth noting that many schools that have successfully raised low-income students' achievement have taken a distinctly different approach. Rather than letting new teachers sink or swim with lesson planning, they provide binders full of model lesson plans and teaching resources developed by veteran teachers (Chenoweth, 2009).

Sinking in Unsupportive Environments

The sink-or-swim nature of many first-year teachers' experiences frequently surfaces as another significant challenge. New teachers often report difficult interactions with colleagues, ranging from "benign neglect" of administrators (Fry, 2007, p. 229) to lack of cooperation or even hostility from veteran teachers.

One first-year teacher, for example, said a colleague flatly refused to share his lesson plans, which was "unfortunate my first year, sinking down and getting no help" (Hover & Yaeger, 2004, p. 21). Another teacher reported that a veteran member of her department came into her classes, propped his feet up on her desk, and disrupted her teaching by throwing out historical facts. "It was so degrading," she said (Hover & Yeager, 2004, p. 20).

More than anything else, novice teachers often appear to yearn for, yet seldom receive, meaningful feedback on their teaching from experienced colleagues and administrators (Fry, 2007; McCormack, Gore, & Thomas, 2006). Regrettably, teacher mentors, ostensibly assigned to provide this support, were sometimes part of the problem, dispensing little guidance, if not bad advice (Fry, 2007). In the words of one new teacher, "Some of the teachers who are mentors shouldn't be. They're not nurturing people; they've just been here the longest, and they want [the mentor position]" (Hover & Yaeger, 2004, p. 20).

How Schools Can Scaffold Success

New teachers bring energy and enthusiasm to their classrooms, but also a specific set of needs. Whereas experienced teachers might bristle at receiving classroom management tips, model lesson plans, and constructive feedback on instruction, new teachers appear to long for such supports. School administrators should recognize that, like students, new teachers need scaffolded assistance. This support should go beyond merely assigning them a mentor, a practice that only reduces five-year attrition rates by one percentage point, from 40 to 39 percent (Smith & Ingersoll, 2004).

If, however, school administrators provide mentoring and guidance, schedule common planning periods to plan lessons with colleagues, and reduce new teachers' workloads by providing an aide in the classroom or fewer preparations, they can cut the attrition rate of their beginning teachers by more than half—down to 18 percent (Smith & Ingersoll, 2004). This early investment in time and resources may result in long-term gains by shortening new teachers' often-perilous journeys from novice to experienced professional.

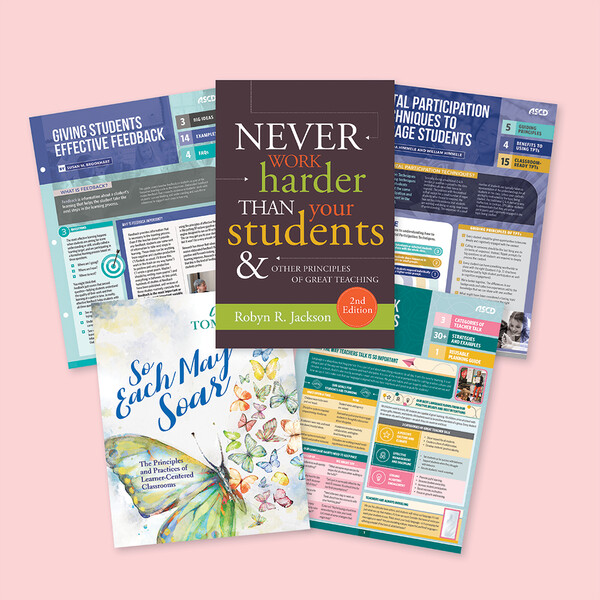

The New Teachers Collection

Whether teachers are just starting out or have been teaching for a few years already, these resources will position them for success.