Wordless picture books tell a story or relate information through illustrations rather than words. As Serafini (2014) notes, wordless picture books “require readers to slow down and pay close attention to the details of the illustrations and the rendering of the visual narrative.” Readers apply their background knowledge and vocabulary to the images in the picture book and make inferences as the story progresses. As they interact with these books, readers make predictions, think critically, and make meaning.

Of course, wordless books sometimes contain a few words, but the text is not the major way information is conveyed. Richey and Puckett (1992) noted that many wordless or nearly wordless books contained some dialogue, labels, symbols, or onomatopoeia as a framing device at the beginning and end of the book. These features help develop students’ understanding of the ideas in the text and build their literacy skills. When used for instruction, books that maximize images and minimize text build verbal reasoning—especially inferencing, rather than decoding, skills.

Introducing Wordless Books

Wordless books are typically found in preschool and primary classrooms. When preparing to teach with wordless books, Lefevre (2018) suggests first starting with simple images and using the following strategies:

Model for students how to use descriptive language for the images.

Invite students to share their verbal descriptions of images.

Discuss how to add more detailed and descriptive vocabulary.

Transition to adding student-generated words, phrases, and sentences to match the images using sticky notes, with the teacher modeling first.

Invite students to add words to images using sticky notes to share with classmates.

Repeat the process with sequential images prior to progressing to wordless picture books.

When wordless picture books are introduced to the class, teachers first model the process of looking at the images and then taking mental note of the details. Teachers can also think aloud about the various aspects of the images, discussing those they believe are key ideas or important details that make the story cohesive. Then, teachers invite students to explore the pictures and talk about what they are seeing.

As students develop in this type of thinking, teachers can ask them to identify what they see in the images. This can start with noticing the things (nouns) and actions (verbs). For example, while sharing Mark Teague’s book Fly (Simon & Schuster, 2019) with students, a 1st grade teacher we observed paused on a page and asked students to share what they saw. They used terms such as branch, worm, sky, clouds, nest, and hop to talk about the pictures. The teacher then prompted students to add descriptions (adjectives) to their terms, such as light blue sky or brown bird and red bird.

Books that maximize images and minimize text build verbal reasoning—especially inferencing, rather than decoding, skills.

Students should also be encouraged to move beyond labeling and vocabulary development to talk about what is happening in the story. On a page from Fly, the students realized that the bigger bird wanted the smaller bird to come out of the nest to get the worm. One student said, “Look, the baby is bigger now. Before, it was smaller in the nest.” Another responded, “Yeah, it has feathers now. The baby wants the worm, but the mom won’t give it.”

These students’ comments demonstrated their verbal reasoning by making inferences about the characters’ motivations. This process continued through the reading of the book as students discussed what they saw and what their observations meant. If students miss important details, teachers can play “I spy” to encourage students to look more closely at the details in the images.

Finding the Purpose

The selection of a specific wordless book should align with the purpose of a lesson. Sometimes, the purpose of the lesson is to develop oral language and vocabulary. Other times, it may be to foster comprehension skills such as predicting, inferencing, or questioning. Still other times, the purpose may be to attend to the sequence of events. Given the range of reasons for using wordless picture books, these resources shouldn’t be limited to primary grade classrooms (Cassady, 1998). In fact, there are many sophisticated wordless books for older readers and multilingual students that can help them build background knowledge, technical vocabulary, and comprehension skills.

Readers of all ages need a range of experiences that build their vocabulary, verbal reasoning, and critical thinking.

One of our favorites for middle and high school students is Shaun Tan’s The Arrival (Scholastic, 2006), a 128-page wordless graphic novel filled with startling artwork that portrays the experiences of an immigrant father as he tries to make a life in a new land for his family. The book is divided into six chapters that challenge students to understand the plight of refugees fleeing from an unsafe country. Notably, the book has won several awards, including the American Library Association’s award as a Best Book for Young Adults in 2008.

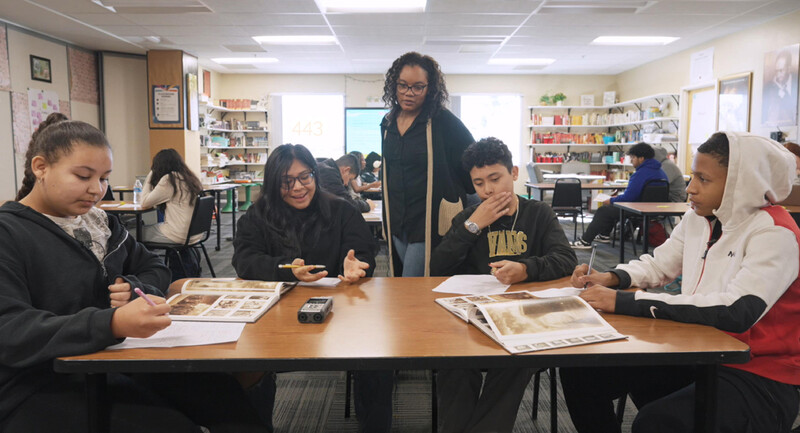

In the video that accompanies this column, high school English teacher Marnitta George uses a collection of wordless picture books to focus on writing dialogue. Her students are working in groups to analyze a wordless picture book. Their task is to construct dialogue that conveys the meaning of the story. In her class, the students first talk about what they are seeing and what the dialogue could be before committing it to writing. They negotiate meaning, engage in critical thinking, use their comprehension skills, and practice expressive language.

Books that have no words are useful across grade levels. Putting them in the hands of students for discussion builds essential comprehension skills. Readers of all ages need a range of experiences that build their vocabulary, verbal reasoning, and critical thinking so that words make more sense as they read print. Lessons that include wordless picture books support a range of purposes and readers, both of which are worthy goals for classrooms.

Show & Tell / Teaching with Wordless Books