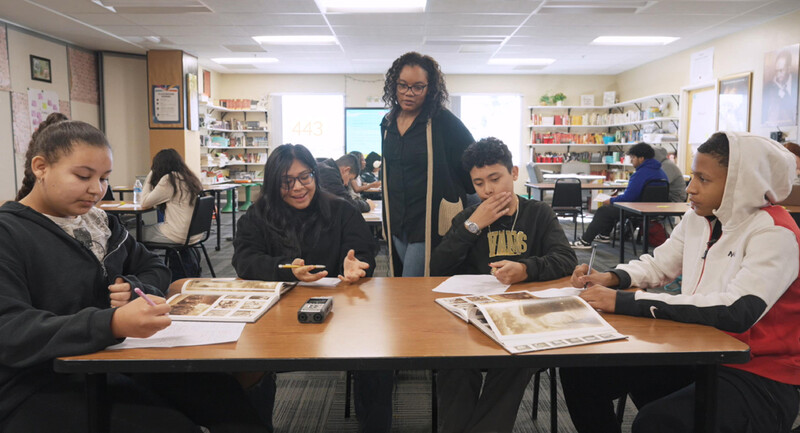

Most reading that is incorporated into the science classroom is nonfiction. Handing out an article or textbook can make students want to shut down, but passing out a novel in science class will have them sitting up and asking questions: Why are we reading a novel in science? Don't we just read textbooks? Reading fiction is for English class, right?

Students will be engaged before they even open the book. Many young adult books feature strong science concepts and can be offered as extra credit or used for a whole-class novel study. Fiction draws students in to both the narrative and the science behind it.

For example, when reading Eye of the Storm by Kate Messner, my 6th grade students were entranced by the descriptions of the massive tornadoes caused by global warming and the main character's journey to try to dissipate them. Pairing the book with videos of tornadoes really brought the concept home. I could have easily given them an article to read, but from past experience, I knew they would not be as interested. Reading the book gave them a desire to learn more about tornadoes.

Finding Books That Work

There are several places that teachers can look for science-themed literature. Librarians and media specialists can help teachers choose books that are aligned with science content standards. Another excellent resource is the "Outstanding Science Trade Books" list, a yearly compilation of K-12 fiction and nonfiction books produced by the National Science Teachers Association. Teachers can also browse local bookstores or seek out English teachers or reading coaches for ideas.

I have used titles from Carl Hiaasen, like Hoot and Scat, as well as Jean Craighead, whose books effectively touch on ecological science concepts. Gail Hedrick's Something Stinks allows students to see the scientific method in action as the main character tries to solve the mystery of fish dying in a local river.

Putting It into Action

There are several ways to read these novels in class. If the teacher chooses to read the book aloud, it would help to give students something to listen for. When reading Something Stinks, for instance, have students identify the steps of the scientific method that are being used.

A second option is to form book clubs within the classroom, either with just one title or with multiple titles on a similar topic. Students can answer discussion questions in groups after reading certain chapters (providing these beforehand will help them navigate the text). Discussion questions for novels are often available on authors' websites, or teachers can come up with their own.

A third option is simply to have students read the book on their own, either at home or during self-sustained reading. Again, the teacher wants to give students a goal to keep in mind when they are reading. If students are reading independently, the teacher can assign a project or offer extra credit by having students connect the science concepts to the reading in a book report.

Even with these activities, nonfiction texts do not need to be omitted. Teachers can bring in supplemental resources from textbooks, the Internet, newspapers, and magazines to add depth to the science concepts that are covered in the book. Nonfiction can help students relate to the fiction in a more informed way; students will be able to make more connections to real-life situations.

One Size Doesn't Fit All

When assigning a book to read in the classroom, it is important to consider students' reading levels. This can also come into play when deciding how students will read the book. If teachers are reading books aloud, they can pause and ask questions to check for understanding and discuss difficult vocabulary terms. When having students form book clubs, teachers can differentiate through grouping or book selection. Another way to differentiate would be to give students a list of discussion questions and let them choose a certain number to answer. Students could also choose from a menu of projects to complete. Presenting students with options gives them more control and leads to a greater investment in their learning.

I have found that in my science classes, students prefer reading fiction over nonfiction. They are much more engaged in the learning and tend to ask more questions. Instead of shutting down with nonfiction articles, my students want to know more. Switching it up develops both their critical literacy skills and their science knowledge.