During the past decade, perhaps no psychiatric disorder has inspired as much controversy within the mental health profession as Juvenile Bipolar Disorder, also called Juvenile Manic Depression. Only in the past few years have clinicians become willing to accept this diagnosis. As a result, educators are just beginning to hear about Juvenile Bipolar Disorder and about treatments aimed at ameliorating its often devastating consequences.

Defining Juvenile Bipolar Disorder

Bipolar illnesses are a subset of mood disorders, of which Major Depressive Disorder is the most common. Adults and children with Major Depressive Disorder suffer from periods of persistently low and hopeless moods characterized by apathy, poor energy and concentration, sleep disturbances, and thoughts of suicide. These depressive symptoms represent one side of the bipolar spectrum. An individual suffering from Bipolar Disorder experiences dramatic fluctuations of mood—from depressive symptoms to manic or hypomanic behavior involving pathological mood elevations characterized by grandiose thoughts and behaviors, promiscuity, recklessness, agitated and sometimes incoherent speech and thoughts, and a profoundly decreased need for sleep.

Although Bipolar Disorder is much less common than Major Depression, with only 1–2 percent of the adult population affected, it is even more devastating. People with untreated or poorly controlled bipolar disease may bounce from depression to mania many times throughout the year and suffer enormously as a result of their mood changes.

Symptoms experienced by children and adolescents with this disorder only partially conform to the classic symptoms of adult sufferers. Instead, children and some adolescents display a much greater percentage of mixed symptoms, expressing both depressive and manic behaviors at the same time or in rapidly fluctuating moods. For example, children may feel irritable and hopeless and yet exhibit increased recklessness and agitated thoughts and behavior at the same time. In addition, bipolar children are prone to intensely angry and sometimes physical outbursts, going from a calm demeanor to absolute fury in a matter of seconds. The 10-year-old boy with Bipolar Disorder who becomes so enraged at having run out of apple juice that he shouts obscenities and throws plates and silverware represents a striking and unnerving aspect of this syndrome.

Not all children with Bipolar Disorder have violent outbursts, however, and the expectation of physically explosive and dangerous behavior has to some extent stigmatized these children. In addition, critics question whether this syndrome of behavior can really be a Bipolar Disorder if it fails to conform to the symptoms that have long been accepted for adults.

Proponents of the Juvenile Bipolar Disorder diagnosis stress that many of these children have strong family histories of the same diagnosis, suggesting a heritable aspect of the disorder and the possibility that as these children age, their behavior will increasingly mimic the more classic form of the illness. In fact, interviews of adults with bipolar illness find that their childhoods were often troubled by the exact behavior that researchers describe as Juvenile Bipolar Disorder, and longitudinal studies suggest that the symptoms of children appear more like those of adult Bipolar Disorder as the children enter late adolescence.

In addition, medication treatments that are effective for adult Bipolar Disorder are often also useful for children, suggesting that the adult and juvenile forms of the illness are similar biologically. Finally, we should remember that until about 20 years ago, most believed that Major Depressive Disorder did not occur in children. As the mental health community realized that depression in children could be diagnosed and treated, children suffering from depression benefited enormously. In a similar fashion, the emerging acceptance of Bipolar Disorder in children and adolescents has led to a vast increase in options and treatments for those who suffer from this extremely difficult condition.

Treatment for Juvenile Bipolar Disorder

Clinicians have used medications—such as Lithium, Tegretol, and Depakote—with some success to help child sufferers with their mood fluctuations. Children using these medications, however, require frequent blood tests to monitor the medications' levels and their effects on such organs as the liver, kidneys, and bone marrow system. Clinicians may also prescribe anti-depressants to combat the depressive episodes, although antidepressant treatment in the absence of a mood stabilizer may generate manic behavior in both children and adults with bipolar illness.

Antipsychotic medications—such as Risperidone, Zyprexa, Seroquel, and Geodyne—have been effective in quickly reining in the violent outbursts that go along with Juvenile Bipolar Disorder, significantly “lengthening the fuse” before further emotional explosions ensue. A common misperception is that the use of these antipsychotic medications must indicate that these children are psychotic. Children with Bipolar Disorder in rare cases may be psychotic, but the explosive behavior and mixed depressed and agitated moods are much more common characteristics.

Children and adolescents with Bipolar Disorder also benefit from counseling and behavioral therapy in both individual and group settings. The explosive moods of bipolar illness can make the inevitable frustrations of growing up extremely difficult. Add to this challenge the frequent co-occurrence of such learning problems as Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, nonverbal learning disorders, and auditory processing difficulties, and it is no wonder that children with Bipolar Disorder often feel demoralized and misunderstood. The combination of an empathic counselor and medication is almost always the best approach to helping children with Bipolar Disorder.

In the Classroom

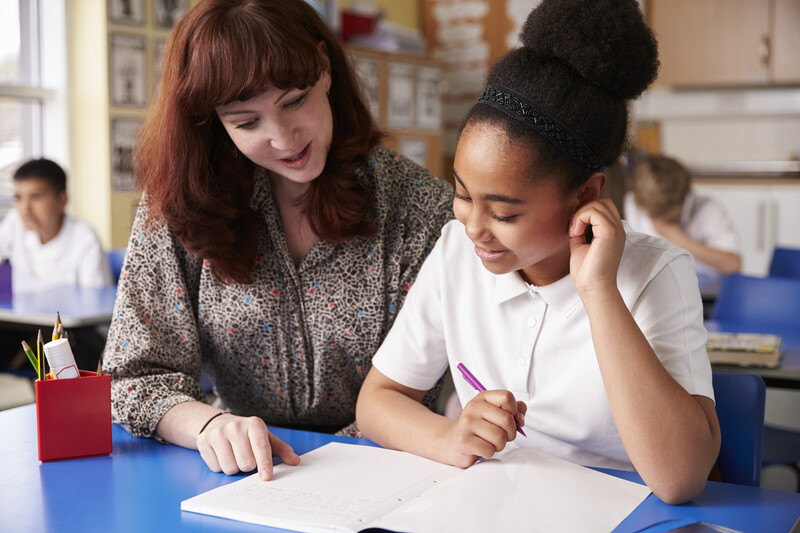

Children and adolescents with Bipolar Disorder can be particularly disruptive in the school environment. Mood swings and emotional volatility, coupled with the possibility of major emotional outbursts, make learning at times difficult for the entire class. For this reason, accurate diagnosis is extremely important. The implementation of appropriate treatment will substantially improve learning, and teachers who suspect any mood disorder should not feel shy about alerting school counselors or nurses. In addition to a clinical examination, children with suspected bipolar disease benefit from neuropsychological testing to identify potential learning disorders.

Students who continue to have a difficult time managing their frustration may need special arrangements so that they do not severely disrupt other students. One effective strategy is to discreetly provide some space outside the classroom to allow students to calm themselves before returning to their studies. This option obviously only works when students do not abuse the opportunity to leave class, and it works best once a student has begun working with a clinician and can better predict when feelings are about to get out of control. In my own practice, some students with bipolar illness have run laps around the school when they have felt emotionally overwhelmed. Such books as The Explosive Child (Green, 1998) and SOS! Help for Parents (Clark, 1996) can help clinicians, teachers, and parents learn ways to cope with the trials of a bipolar child.

Juvenile Bipolar Disorder can be extremely disruptive. It derails development, strains friendships, and stifles learning. As clinicians and educators come to understand the diagnosis of Juvenile Bipolar Disorder, however, the children who suffer from this problem have a much greater chance of success than was possible even a few years ago.