Because oral-communication skills—specifically capability in discussing substantive issues—aren't assessed on high-stakes tests, they're often overlooked in schools. But these skills are just as important as reading, writing, and mathematical skills for success in college, career, and life. They are vital in almost every job and civic role, and for the health of every family. Individuals, families, and communities usually talk about issues they're concerned with, solutions to difficulties, or new opportunities before they write them down or act on them. Problems are solved through honest, productive dialogue that leads to innovative solutions and impactful action.

Young people need to become skilled at such dialogue. If students cannot express themselves clearly and effectively by the time they leave high school, when do we assume they'll develop those skills?

Even in schools where discussion is common, classroom conversations are often dominated by a few students, while other students remain silent or disengaged. All students deserve rich opportunities to develop their verbal communication skills, and it is an equity imperative for us to make sure their thoughts and voices are heard in schools.

So how do we ensure that all students acquire the ability to express ideas with clarity, precision, and eloquence? How do educators ensure that students engage deeply to understand multiple perspectives and grapple with difficult issues collaboratively? How do we empower all students to have a voice in the conversations that will shape their lives and their contributions to the world?

Great Discussion as a Gateway to Success

Schools connected to the EL Education (formerly Expeditionary Learning) network are deliberate about building students' discussion skills. EL Education supports more than 150 public schools nationally, as well as several large school districts that use our open-source English language arts curriculum. As EL Education leaders and former teachers and school leaders ourselves, we've seen firsthand how explicitly teaching discussion skills is integrally connected to promoting students' sense of belonging and agency.

At Casco Bay High School for Expeditionary Learning in Portland, Maine, for example, discussion is prioritized as a gateway to success for all students. Through intentionally designed advisory, classroom, and whole-school meeting structures, students regularly lead courageous conversations in which they discuss issues of concern, such as immigration, transgender rights, white privilege and racism, and mental health. The conversations often echo broader national and global debates, but they are also urgent and personal for students.

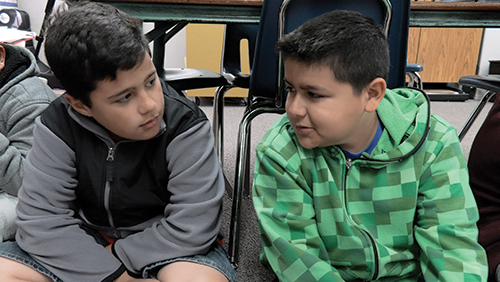

Juniors at Casco Bay High School in Portland, Maine, discuss segregation in their school and community. Photo courtesy of EL Education.

These conversations are more than an exercise in practicing communication skills, says Casco Bay principal Derek Pierce. They model "what a functional society can look like. That's the goal. So that [students] can experience here what community can really be, so that they can build communities that are just as effective, as loving, as compassionate wherever they go." (To see more about these courageous conversations, see Casco Bay's video "Brave and Honest Communication in Crew" at https://vimeo.com/356118214.) Casco Bay's commitment to these kinds of conversations is not a trade-off with creating successful academic outcomes for students. Just the opposite: It's a foundation of the school's success in academics. Casco Bay is an award-winning public district school, and since it opened in 2005, 98 percent of its graduates have been accepted to college. Many Casco Bay students are the children of refugees, and many alumni are first-generation college students with a wide range of home languages and sometimes gaps in their schooling. For these students especially, participating fully in courageous conversations is at the core of Casco Bay's commitment to equity and to building all students' agency and positive identity.

By creating opportunities for students to bring their whole selves into discussions of difficult topics, Casco Bay teachers support students to become not just effective learners, but also ethical individuals who contribute to building a more just, equitable world. With the right scaffolding and attention to school culture, this kind of conversation can happen in any school. Classroom routines that emphasize both empathy and accountability make it possible for students everywhere, in all grades, to discuss sensitive topics passionately and respectfully.

Making Time for Courageous Conversations

The first step toward fostering strong discussion skills is carving out meaningful time. At Casco Bay, and in other schools throughout the EL Education network, school leaders make space for courageous conversations through three regular structures that impact every student in the school.

Casco Bay students circle up to address community issues. Photo courtesy of EL Education.

Crew Meetings

At every grade level, students start every day by circling up in an advisory period with a small group of peers to which they've been assigned. The "crew" often stays together for two to four years. Students get to know and care about one another through honest and courageous dialogue about issues that impact them personally. They push and support each other to be better students and better people. Many students describe their crew as their school family.

Powerful Schoolwide Conversations

At Casco Bay, students across the school convene monthly in their crews to discuss a topic chosen by a "cabinet" of student leaders. Student leaders provide a common lesson plan that is often facilitated by a student leader in the crew. For example, in a conversation about race, students used a fishbowl protocol in which students of color discussed the prompt first while white students listened, then the groups switched. The protocol provided a structure for students to engage their peers with mutual curiosity and respect.

Other EL schools hold weekly, monthly, or quarterly community meetings in which students gather with grade-level peers (or in some schools, with students across multiple grades) to discuss, debate, celebrate, and affirm their shared values. Often community meetings are planned and facilitated by a small group of students. Students decide on the meeting's topic, create rituals and activities to honor peers' accomplishments, and even address conflicts or breaches of school norms through conflict resolution discussions.

In 2017, Casco Bay student Atak Natali was both informed and empowered by these schoolwide conversations, which served him well in a painful situation. As a freshman, Atak and some friends, all students from refugee families, were walking to their bus stop when they were attacked by a stranger who used racist language and physically assaulted them. Although no one was badly injured, the boys were humiliated and frightened. The incident compromised their safety and sense of belonging in the community. After Atak told his crew about the incident, teachers didn't just expect him to move on or "get over it." They made a deliberate decision to set aside the regular schedule and hold courageous conversations in Crew groups. Crew leaders facilitated a dialogue about how hateful actions impact individuals and the community, and about what students could do to respond productively. Students' suggestions were brought forward to a cabinet of student leaders. They ultimately organized a school march downtown, where every student and staff member stood up to racism in support of their students and peers.

A student leader, Farhiyo, explained, "I don't think we would have had a very effective courageous conversation that Monday or responded the way we did if we were not prepared through other conversations that we've had." The school received a state human rights award for how it responded to this incident. (The story of the school's response is captured in the video "Walking in Solidarity," viewable at https://vimeo.com/234881786.) Frequent Classroom Discussions

Teachers in all classes at Casco Bay create opportunities for students to connect their learning to their life experience. Using discussion protocols and holding students accountable to shared norms for speaking and listening with respect and compassion helps make the interactions safe for students.

Protocols provide a step-by-step process and time limitations for students to participate equitably in conversation. Students who typically hold back have a designated entry point and a safe way to contribute their ideas. Students who tend to dominate a discussion must share the air with peers, and listening is valued just as much as speaking.

Essential Steps for Fostering Courageous Dialogue

Develop "Shared Commitments" for Discussion

Students at Casco Bay hone their speaking and listening skills by exploring tough issues with curiosity and compassion. Teachers scaffold these skills intentionally, first by developing conversation norms with their students. The norms are not rules passed down from the teacher. They are generated by the students themselves, in response to questions like, "What would someone look like if they were listening to you respectfully?" "What words would you use to show that you really want to hear their perspective without judging them?" The conversation norms that result are posted in the classroom so that students (and teachers) can revisit and reflect on them. For instance, the "Oops and Ouch" norm holds that if a statement feels hurtful, the injured person lets the group know by saying "ouch" and explaining why. The peer who inadvertently made the hurtful statement can say "oops," apologize, and rephrase or explain her perspective without the hurtful words.

Shared commitments give students a common language for asking questions and agreeing and disagreeing respectfully. Phrases like "I acknowledge," and "from my perspective," and "what I hear you saying is" allow all students to participate and feel safe and respected during discussions. (See a video example of Casco Bay students creating class norms at https://vimeo.com/124448656.) Build Trust and Empathy

Teachers also create a trusting environment for discussion by modeling honesty and vulnerability themselves. For example, when a teacher apologizes to students for a mistake that impacts them, students learn that apologizing is hard for everyone, and that it's the way we begin to repair our community. Even the youngest students can learn this key discussion skill. Morgan Grubbs, a teacher at Capital City Public Charter School in Washington, D.C., closes each day with her 1st graders by making space for them to appreciate or apologize to a classmate. "Friends seeing other people being vulnerable helps them to do it too," she explains. "That vulnerability sends a powerful message that it's okay not to be right all the time. We can all grow and change our minds and our behavior."

Modeling and redirecting students to use "I statements" ("I was upset when you …" instead of "You are acting like a …") also builds students' skills at open discussion. When teachers model addressing conflict directly rather than complaining about a person, students learn that honest communication is brave and effective. "It's okay to be uncomfortable when you're having a courageous conversation, because that's part of the growth and learning," says Arria Coburn, principal of The Springfield Renaissance School in Springfield, Massachusetts. The combination of shared discomfort, honest perspectives, and deep listening nurtures students' empathy and deepens their understanding of complex issues (as evidenced in an Edutopia-created videoclip on the Springfield Renaissance School, "Building Perspective Through Meaningful Discussion," available at https://youtu.be/TkghOJgSTlg. Use Protocols to Provide Equal Time and Access

Protocols honor multiple perspectives and give students "guard rails" so that they can take risks to participate without fearing that what they say will be laughed at or ignored. For example, students in EL Education schools often use the 4A's protocol to prepare for a discussion on a controversial claim. They record one assumption the author makes, one thing they agree with, one thing they want to argue with, and one question they want to ask. Then students each begin the discussion by sharing one of their "A" statements. This gives every student a choice and a voice.

Protocols and conversation norms also support students in talking about their own personal experiences, even their biases, within the context of academic content so that academic discussions are more meaningful. This doesn't mean students are excused from rigorous academic or evidence-based thinking. Instead, they are asked to examine and think critically about all the evidence, including their own experiences. They see that "evidence" includes many kinds of sources, and every source—from personal experience to expert testimony, photographs to textbooks—contains some level of bias.

Discussion should never be a pop quiz or "gotcha" activity. It's important to give students questions in advance and allow them time and support to reflect on and gather their evidence from their reading before asking them to discuss. Reading and synthesizing information before discussing sharpens students' thinking.

In elementary school, this might mean examining photographs or close reading short texts to gather facts relevant to the discussion. Older students can take on more complex topics with significant historical, political, and social implications. Seniors at Codman Academy in Boston, for example, spent months digesting the United States Department of Justice's report on its investigation of the Ferguson, Missouri, police department and discussing police violence in communities of color (See a video on the project at https://vimeo.com/147860127.) That's a challenging task for students who can't yet vote, but it also empowers them to be informed, motivated civic actors who are more likely to vote. Fifth graders at Conway Elementary in Escondido, California, Share their stories in connection with a study on human rights. Photo courtesy of EL Education.

Creating Changemakers

The seeds of building community and building bridges between communities are planted in conversations students have with each other every day. When those discussions are intentionally respectful and relevant to students' lives, students become changemakers—public speakers, oral historians, writers, politicians, community organizers, and scholars. They don't have to wait until they're grown up to make a positive difference in the world.

As Casco Bay's Pierce notes, "The sum of those structures and the million everyday actions of people in those structures are what lead to kids having the convictions and courage to bring their full voice to the world." That conviction shines through in the voice of Atak Natali, reflecting on his experience being targeted and how to address hate in our nation:

Schools should have courageous conversations like Casco Bay does. If they gave the same support as I and my friends got, then it might influence … others not to do what that young adult did. And that would just make the world a little bit more peaceful.

Reflect & Discuss

➛ A leader quoted in this article says he wants discussion to spread through his school to give youth "a sense of what community can really be." Watch the video of "Crew" conversations at this school, linked on p. 40. What do you see in the video that reflects a strong community?

➛ Have any students at your school been targeted or threatened in an incident like the one described at Casco Bay? How could you have made student discussion more a part of your response?