- Why is the change necessary?

- How much change needs to occur?

- Where should the change occur?

- Who will participate in the change process?

Just as new stop signs won't necessarily improve drivers' behavior, reforms that don't change students' learning strategies won't boost achievement.

Too often, schools and districts implement restructuring efforts that go as planned, yet fail to improve students' learning. After hearing many stories about reforms that weren't successful despite significant energy and resources spent, we conducted a thorough review of the literature on reforms in schools. We found clear patterns when we contrasted reform initiatives that failed to affect student performance with initiatives that effectively improved learning.

Our counterintuitive conclusion: The levers that can change schools most efficiently are often the least effective at improving student learning. This conclusion challenges deeply held beliefs about school improvement. To understand why it's true, let's consider the complex relationship among four important questions about change:

Aligning the answers to these four questions in a manner that improves student learning is surprisingly difficult. It's also among the most important work that a school leader must do.

The first question, Why are we doing this? is powerful. When people share an understanding of why they're engaging in certain actions for change, they can align their efforts toward the crucial goals. The amount of effort people exert—and where they direct that effort—looks different when their goal is to comply with an external mandate than when their goal is to change a key process to improve student learning. Being clear about why is essential; the answer becomes the premise for the other three questions.

How much change is needed? asks how much effort people need to invest to move things forward. We've identified three magnitudes of change: maintaining the status quo (meaning existing beliefs and processes are carried forward); transactional change (meaning incentives and requirements drive changes in processes); and transformational change (meaning individuals develop new beliefs, insights, and skills that result in entirely different conceptions of themselves).

Where should the change occur? asks where we should invest efforts to raise student achievement. In education, we've found that virtually every initiative seeks to address one of five areas of leverage: structure (such as schedules and logistics); sample (such as grade configurations and student grouping practices); standards (expectations for quality); strategies (teachers' instructional strategies and students' learning strategies); and conceptions of self (what students believe about themselves as learners and what educators believe about teaching). By understanding the advantages and disadvantages associated with these areas of leverage, educators can better prioritize their efforts.

Who will participate in the change process? seems to be the easiest question to answer, but it may be the most elusive. If educators engage in a significant change process but students don't notice any difference in their opportunity to learn, have we implemented meaningful change?

Allow us to use an analogy to clarify the challenges and opportunities associated with aligning why, how much, where, and who. Suppose that rather than serving your community as an educator, you're its director of traffic safety. You and your crew work hard every day to ensure and improve safety. What might happen if you don't thoughtfully consider these questions?

Some change efforts simply maintain the status quo; they leave structures, standards, and strategies in place, but deploy them in a slightly different context. With this approach, Why change? isn't really about improvement, but about reducing any variance in existing practice. Maintaining the status quo can include rolling over dates to establish the next school year's calendar, providing orientation to new teachers, or teaching a lesson to a new group of students using the same strategies as in the past.

To maintain the status quo as director of traffic safety, you'd ensure that existing stop signs were properly installed and visible at every intersection. Your crew would diligently trim tree branches that obscure stop signs, apply new reflective paint, or replace old poles. If this maintenance didn't occur, the results would be catastrophic—confusion at intersections and accidents. But as long as your crew maintains the intersections and assures proper signage, drivers will take this work for granted. They'll use a familiar set of strategies: Stop, look in both directions, and go.

Ensuring that existing structures are preserved and practices are consistent is an essential management task. Without it, chaos would ensue. However, no matter how much effort is put forth to maintain the status quo, these efforts are not about improvement. In schools, they don't improve standards or strategies. To the contrary, they ensure that those who are already served by the system can continue to use the same strategies to obtain the same results.

Other reforms lead to transactional change. Here, Why change? is driven by compliance. Organizations create new incentives, adopt new structures, or modify processes so individuals can efficiently use existing strategies to yield different results. In education, transactional changes could include deploying a new grading scale, modifying the schedule to increase student contact time, or adopting a template to align existing curriculum to new standards.

When examining how transactional change relates to school improvement efforts, it's crucial to understand who needs to change for the initiative to be implemented. Consider this traffic safety scenario.

A government agency creates new safety standards, mandates you to follow them, and deploys safety score measures and incentives to monitor results. Key components include taller, larger stop signs. Some stop signs will require solar panels to power a flashing red light.

Eager to comply, your community adopts these standards. You work with your purchasing manager to acquire dozens of new poles, signs, and panels. Your crew even engages in days of professional development to learn how to install the complex solar panels. The signs require a new type of cement to ensure stability. Your crew is working more hours than ever, and although some crew members are thriving, others express frustration and talk of the good old days when they could get their jobs done by trimming branches or applying fresh paint.

A year later, you receive your new traffic safety scores. You're shocked to see there have been no improvements. To understand how your crew could work so hard, yet your safety scores stay the same, you hold a focus group with 12 citizens. Most of the drivers barely noticed the new, larger signs; only a few noticed the blinking lights. They report using the same strategies they had in the past; stop, look, and go.

You leave the focus group deflated. Despite the efforts of your crew, the community seems mired in the status quo. Driving the well-worn path between city hall and your house, you approach a familiar intersection and glance in both directions. As usual, there's no traffic. You slow down—but don't stop—and roll past one of the new stop signs. Then it hits you; for the drivers, nothing has changed.

The irony of transactional change is that our best efforts to adjust and comply can still maintain the status quo for those we serve. Whether installing new stop signs or responding to education mandates, leaders need to guide change to ensure compliance. However, we can't assume that our efforts—no matter how significant—will change students' beliefs or help them adopt new learning strategies.

For example, to comply with new evaluation requirements, teachers are often asked to identify the standards they're addressing in each lesson by posting them in their classroom. The intent is to ensure that the new standards aren't placed on a shelf and forgotten. The assumption is that if teachers post the standards, students are more likely to meet them.

But how will complying with this transactional requirement yield different results if lessons are taught no differently than in the past? If posting of the standard isn't accompanied by new strategies that help students establish learning goals, self-assess, and monitor their progress, then for students, nothing will change.

Transformational change occurs when individuals are empowered to engage in work differently because new beliefs about their capacity support the development of new skills. Such change for a teacher may occur when he realizes the value of providing students with meaningful feedback—as opposed to just grades—after teaching students to use standards to monitor their own progress toward learning goals. A student may realize such a change when she pursues new leadership opportunities after developing self-confidence and new skills in a public-speaking class.

When transformation occurs, the why runs deeper than compliance. The drive to do the same work only better is replaced with the understanding that the work itself must change. As a result, the role of the learner must change as well.

Suppose you decide to identify the intersections where the most accidents occur so you can take action to improve your safety metrics. After analyzing reams of data, you identify six intersections and decide to install stoplights. The stoplights require significant restructuring; intersections must be widened, electricity rerouted, and trees removed. Politics ensue, but eventually the plan gets approved. You restructure your department, establishing an electronics team and a heavy equipment team. The teams go through extensive training and emerge with new skill sets.

After months of effort, the new lights are installed. For your crew, this experience has been transformational; they've developed new skills and view their capacity and roles differently.

In the first few months, accident rates decline moderately. But the accidents that do occur are more serious because people drive faster through the new, larger intersections. At your request, a new ordinance is passed that doubles fines for speeding. Ironically, increased police presence at these intersections results in the documentation of more infractions than before, lowering your safety score.

After a few months, drivers in your community fall into familiar routines. Rather than stopping and looking—as they'd done in the past—they aren't even attuned to the traffic. If the light's green, drive; if it's red, stop, wait, and then go. At times, drivers have to sit at a red light for 30 seconds although there are no other cars near the intersection.

You've restructured your department. Your streetscape looks entirely different. Professional development has transformed the capacity of your staff. However, for drivers, the new stoplights have merely resulted in transactional change. Drivers deploy existing skills through slightly different processes, under the threat of new consequences.

A transformed organization may only yield transactional change among those it serves. Switching to block schedules, smaller schools, or one-to-one technology requires dramatic restructuring and hours of professional development. But who develops new strategies to participate in such changes? Too often, students—who should benefit most from the change—engage in different processes, but they have the same learning experiences as in the past.

Imagine that you invest significant time, effort, and energy in purchasing and training teachers to use new technology, but teachers deploy the technology in a manner that yields the same curriculum, instruction, and assessment as before. Or you invest time developing supervisors' understanding and skills associated with a new teacher evaluation framework, but the framework is used in a way that teachers merely view as more visits, different forms, and new deadlines.

The end results in these scenarios are counterintuitive. The organization has been restructured. The individuals implementing the change are transformed. But the individuals using the system simply experience a transactional shift. They play the same role and use the same strategies as in the past.

As traffic safety director, frustrated by the lack of change in driver behavior, you take a step back and consider the scenario from the drivers' perspective. While you've focused on safety, drivers care about getting through each intersection quickly. Instead of asking, How can I get drivers to stop? You ask, How can I help drivers get to their destination quickly and safely?

You read about a strategy that eliminates intersections: roundabouts. In communities using roundabouts, the rate of serious accidents decreases by 90 percent, whereas the number of vehicles passing through each intersection per hour increases. You're concerned that you may engage in another restructuring effort that yields no meaningful change. So you contact a colleague in a nearby community who's an advocate for roundabouts. You share your concern about the ability of drivers in your community to change: Given their ambivalence in the past, will they develop a different set of strategies?

"I was concerned about that, too," replies your colleague. "Then I realized that I'd never really asked drivers to change. I was so busy training my crew and restructuring that I assumed drivers would change as well. But we can't expect the outcomes to be different than in the past unless we empower drivers to see their role differently and develop new behaviors."

A roundabout differs from previous restructuring efforts because it requires—and supports—use of different driving strategies. The new structure is based on a different set of assumptions (there is no intersection). It requires new strategies (the center circle requires drivers to make an active response). It's simpler (rather than looking both ways, drivers need only look to the left) and yields different processes (rather than stopping when no traffic is approaching, drivers are free to proceed through). Finally, it empowers each driver as the active agent in the process.

What might a school restructuring effort that empowers students as the most critical component in the learning process look like? Implementation of new standards would begin with the premise that students should be taught to be the primary users of the standards. Teaching students to establish their own learning goals and monitor their own progress through formative assessments would become part of the curriculum. Students would be taught how to design activities that guide their own progress toward each standard. A shared language of quality among teachers and students would be seen as essential. As students learned skills and strategies that empower them to be active agents in the learning process, their engagement, commitment, and learning would grow.

Viewing change through the eyes of those who are intended to benefit from that change clarifies the areas of leverage most likely to improve results. All learning, and all change, is personal. Meaningful change occurs when students shift their conceptions of themselves because they've been empowered to use new strategies that guide them toward new standards. This can occur independently of the structural changes typically associated with reforming schools.

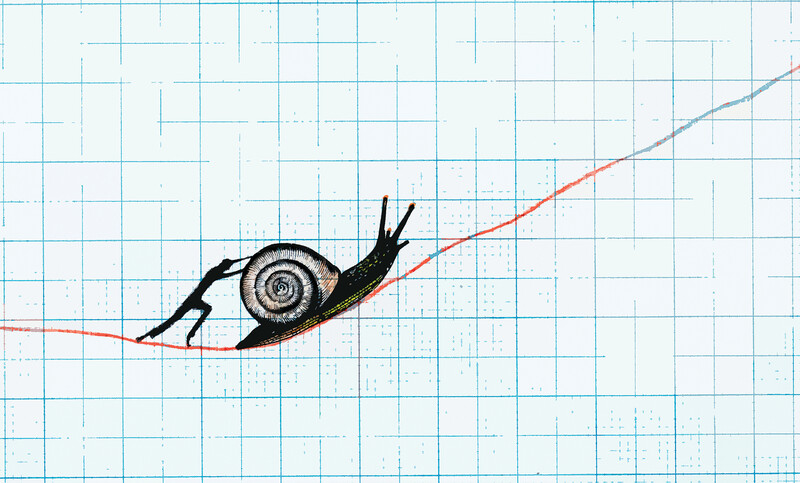

Structural changes are enticing because they're tangible (We had a large high school; now we have four small high schools). Yet too often, these changes are the equivalent of taller stop signs. The people who control the system engage in significant change efforts, but those who use it utilize the same beliefs and skills they applied in the past. Restructuring schools is hard work—but not always the right work.

Aligning the reason for change, the magnitude of change, the area of leverage where the change should occur, and the people who participate in that change is challenging. But it's the only way we know of to ensure that the changes we make will support the outcomes we seek.

End Notes

•1 Frontier, T., & Rickabaugh, J. (2014). Five levers to improve learning: How to prioritize for powerful results in your school. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

•2 Marzano, R. J.,Waters, T., & McNulty, B. A. (2005). School leadership that works: From research to results. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.