When I first stepped into Lyn Jobson's school in Melbourne, Australia, and saw the open classrooms, I must admit that I flashed back to some bad memories of my own school days in the 1970s, when our "open classrooms" had wide breezeways into shared space instead of doors and were separated by thin, movable walls. What I recall most was the noise, distracting outbursts from other classrooms—and carpenters turning up circa 1980 to reinstall the doors.

Yet Jobson's K–8 public school, Alamanda College, was different.

I had arrived shortly after lunch, during daily independent learning time. In every class, I saw students working diligently on individual tasks drawn from learning progressions posted on classroom walls. You could hear a productive din across the school, but far from being distracted, the students were focused on accomplishing self-guided tasks. They were eager to complete those tasks, show them to their teachers, and move on to the next challenge in their self-paced learning. The teachers were mostly young, but enthusiastic and adaptable—which was fortunate because the new school had mushroomed from 160 students to 1,000 in a single year.

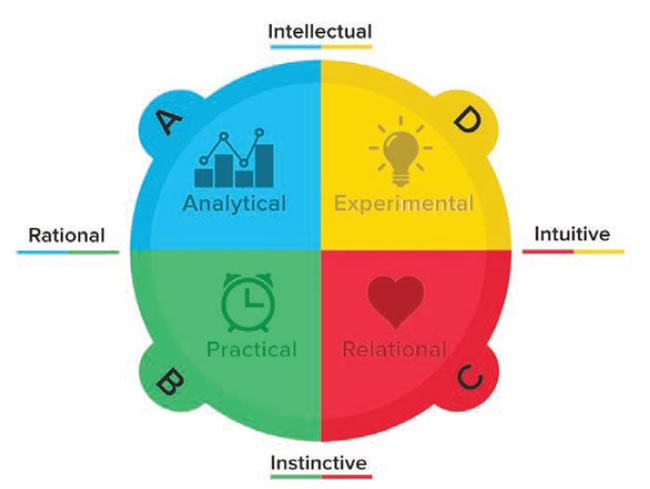

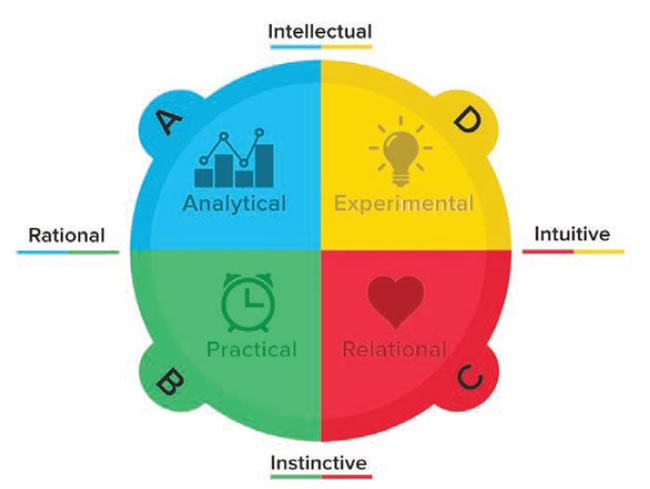

Change is never easy, but rolling out an innovative teaching approach atop massive influxes in enrollment? How did they manage it? Lyn gave an intriguing answer: She spent a lot of time thinking about her teachers' thinking preferences. In response to my raised eyebrows, she pointed to a four-colored wheel on the wall of the teacher lounge: the Herrmann Brain Dominance Instrument. The instrument's framework for whole-brain thinking categorizes individual thinking preferences into the four domains of analytical, practical, experimental, and relational (see fig. 1). Figure 1. Herrmann Brain Dominance Instrument

<ATTRIB> Source: Herrmann International, www.herrmannsolutions.com. Copyright © 2016 Herrmann Global, LLC. Used with permission. </ATTRIB> What Are Thinking Preferences?

In the months that followed, I began noticing four element thinking preference frameworks all over—just as a new word seems to appear everywhere after you learn it. A Colorado school administrator told me his district was using one such framework, called Emergenetics. McREL's human resources director, recently arrived from Accenture, brought with her the DiSC assessment—a four-letter acronym for, you guessed it, four thinking styles. I also recalled that the Gallup organization groups its strengths framework into four main domains. Although these frameworks use different terms, they all generally advance the same theory: that people respond differently to challenges depending on their dominant thinking preferences. Those thinking preferences relate to the left hemisphere versus the right hemisphere of our brains and to fast thinking (which is automatic, frequent, emotional, stereotypic, and subconscious) versus slow thinking (which is effortful, infrequent, logical, calculating, and conscious) (Kahneman, 2011). Put left-right and fast-slow together, so the theory goes, and you get these four thinking preferences:

1. Thinkers (analytical, logical). Our left brains are home to logical analysis; thus slow, left-brain thinking is objective and analytical. People who demonstrate this thinking preference often press for clarity before proceeding. Others may accuse them of "paralysis by analysis."

2. Doers (sequential, action-oriented). A thinking preference for fast, left-brain functioning reflects a preference for sequence and routine. People with this thinking preference are pragmatic and action-focused; others may accuse them of being hasty, judging, or compliance-driven.

3. Energizers (imaginative, big-picture). Our right brains are home to big-picture synthesis. People who default to slow, right-brain thinking are creative and love ideas. However, they can annoy others by glossing over details or moving from one idea to the next without taking action.

4. Connectors (interpersonal, social-oriented). Our right brains are also considered the source of empathy—the result of automatic, emotional thinking that sizes up others' nonverbal cues. People with a fast, right-brain thinking preference are likely to grasp undercurrents in group dynamics and seek to preserve group cohesion.

Why Does Complex Change Sometimes Falter?

What do thinking preferences have to do with leading change? Perhaps quite a lot. Years ago, a team of researchers at McREL conducted a large meta-analysis of research on school leadership (Marzano, Waters, & McNulty, 2005). The biggest takeaway was that better school leadership (as defined by 21 key behaviors) was linked to better student achievement.

But one perplexing finding also emerged. A few outlier studies among the dozens included in the meta-analysis actually found that some principals who appeared to demonstrate all the right leadership behaviors did not lead schools with high levels of achievement (Goodwin, Cameron, & Hein, 2015). The researchers wondered whether a possible explanation for this paradox might be that some leaders could be perfectly capable of managing incremental improvements (and thus regarded as good leaders), but ineffective at leading complex changes.

In a follow-up survey of 900 principals, the researchers sought to tease out (among other things) whether the kinds of change schools experienced—relatively routine, incremental, first-order improvements versus more complex, second-order changes that often feel like the wheels are coming off—had any bearing on the perception of leadership effectiveness. They found that when mired in complex change, leaders often appeared to come up short in these areas:

1. Input. People felt excluded from important decisions about the change effort.

2. Order. People felt the school lacked standard operating procedures or routines.

3. Communication. People required greater clarity and more dialogue with leaders.

4. Culture. People felt a diminished sense of personal well-being and group cohesion.

Connecting the Dots

Consider those previous lists for a moment: four thinking preferences that affect how different individuals experience change, and four leadership behaviors that suffer when schools undergo complex, transformative change. It's far from airtight, yet we might theorize this pattern when we connect the dots:

1. Analytical, logical thinkers want to be convinced of the necessity of the change. They need to be certain that it's absolutely the right course to take, and that it's not an illogical break from the past. They may resist change if the leader doesn't provide opportunities for input so they can participate in decision making and understand the logic of the change.

2. Sequential, action-oriented doers are often the first to act, but they need to understand exactly what they're being asked to do and to feel confident that they have the skills and knowledge to do what's being asked of them. They may resist change if the leader does not help them re-establish routines and order.

3. Imaginative, big-picture energizers need to understand where things are going and to believe the change is consistent with their ideals. They may resist change if the leader doesn't provide two-way communication to assure them that the leader shares a vision with them.

4. Interpersonal, social-oriented connectors want to preserve group norms. They may fear that change is eroding the group's social harmony or their own social status, and they may resist the change unless the leader works to restore well-being and cohesion to the culture.

Although these connections may be compelling, we should interpret them with caution. For starters, thinking preference research has its critics, who point to the lack of independent peer-reviewed studies to validate it (Allinson & Hayes, 1996) and to the fact that neuroscience doesn't show that brain activity occurs neatly in one side or part of the brain (Hines, 1987). A bigger concern may be that people don't always fit neatly into a single category; most of us engage in all four types of thinking at some point, so we ought to think of preferences as hats that we all wear, even though we may be more comfortable in some than in others. Finally, truly connecting these dots will require future studies to align people's thinking preferences with their reasons for resistance and impressions of leaders during times of change.

Leaders Must Be Out of Their Minds

Nonetheless, we might safely draw this point: Leading change is not a one-size-fits-all proposition. Just as teachers need to differentiate instruction, leaders need to differentiate leadership. That requires getting out of your own head—or switching hats—long enough to appreciate that others may not respond to change the same way you do.

For example, a leader who's an analytical thinker may assume that people appreciate his conscientiousness and caution in making sure the school is choosing the right path; yet followers who don't have this preference may be eager for him to try something, anything, to see whether it works. Another leader, who's an action-oriented doer, might assume that others appreciate her decisiveness and clarity; yet some followers may question her logic or wonder where they're going and whether they're going too fast. A leader who's a big-picture energizer may assume she can captivate and inspire people with her vision and let the details sort themselves out; yet followers may need specifics to feel confident in moving ahead. Finally, an interpersonal connector may assume that others appreciate his efforts to maintain the culture and create group cohesion; yet some followers may fear they're on a complacent sinking ship that needs some shaking up.

In the end, perhaps the biggest lesson leaders can take from this knowledge of thinking preferences is that when leading change, they need to address the whole mind—which, as it turns out, maps nicely onto what leadership theorist William Bridges (2009) described as the 4 Ps for managing change. Bridges asserted that when people experience change they feel a loss of control, which leaders can restore in four ways: by giving people input to logically understand the purpose of the effort; restoring a sense of order by describing clear next steps, or a plan, for getting there; creating opportunities for communication and dialogue to see the big picture; and attending to a disrupted culture and restoring well-being by showing everyone the part they can play.

What Works with Teachers Works with Students

Educators aren't the only ones with individual learning preferences that affect how they respond to new challenges. As I think back to Lyn Jobson's school in Melbourne, Australia, the magic of those classrooms seemed to be that they gave students control over their learning—the ability to see where they were going, understand the purpose of their daily work, talk to teachers about their progress, and work with classmates to get the job done. Perhaps if my school back in the 1970s had considered all of those needs when attempting to implement the open classroom model, we might have been spared the carpenters.

<P ID="el0616-goodwin-video"><!-- Start of Brightcove Player goodwin videohttp://bcove.me/q06bb86uhttp://video.ascd.org/services/player/bcpid4724779752001?bckey=AQ~~,AAAAAmGjiRE~,escbD3Me8-zUoJnK8aeQaP9MrJoLVV7m&bctid=4901491291001--><!--div style="display:none"></div--><!--By use of this code snippet, I agree to the Brightcove Publisher T and C found at https://accounts.brightcove.com/en/terms-and-conditions/. --> <!--<iframe src="https://players.brightcove.net/10228042001/default_default/index.html?videoId=4901491291001" style="position: absolute; top: 0px; right: 0px; bottom: 0px; left: 0px; width: 100%; height: 100%;"></iframe>--><!-- This script tag will cause the Brightcove Players defined above it to be created as soonas the line is read by the browser. If you wish to have the player instantiated only afterthe rest of the HTML is processed and the page load is complete, remove the line.--><!-- End of Brightcove Player -->