Schools need to go beyond the traditional models to make connections with low-income communities and bring parents in as partners. We present here three successful approaches: An elementary school takes tutoring and parent meetings right to the home turf of students living in a housing project. An ethnically diverse school creates a full-time parent center with a bilingual staff. And administrators from schools in rural West Virginia and Missouri describe how they revived home visits.

Meeting Students Where They Are

Christopher D. Wooleyhand

At Hillsmere Elementary School in Annapolis, Maryland, we have successfully reached out to the community that many of our low-income students call home. Twenty-five percent of Hillsmere students live in a public housing community called Robinwood, developed as part of the urban renewal program in 1970. Robinwood's 433 residents face many challenges, including increasing crime, sporadic violence, and generational poverty; all of them live at or below the poverty level. Hillsmere has taken a three-tiered approach to addressing the needs of students living in Robinwood.

Going Beyond the Schoolhouse Walls

Courtesy of AACPS Schools

Betty Ann Weekly, director of Robinwood Recreation Center, reviews Hillsmere Elementary students’ work at the after-school homework program located at the center.

Since September 2005, staff members at Hillsmere have volunteered during the school week to assist students with their homework at the Robinwood recreation center. Although this may seem like a simple gesture, it has created a positive climate within the school and community. When students see their teachers in their neighborhood on a regular basis, they receive a powerful message that the teachers' commitment goes beyond the walls of the schoolhouse.

This outreach program has provided more than instructional benefits. Parents often come to the recreation center to meet with teachers and confer about their concerns. Parents who have difficulty finding transportation to the school are now included in important decisions regarding their children. In essence, the recreation center has become a hub for communication between parents and teachers. Teachers who are unable to volunteer know that if they need to speak with a parent, they can arrange for a meeting at the center.

The school holds formal parent-teacher conferences for students from Robinwood at the recreation center. If certain parents fail to show up, teachers have been known to knock on doors and hold conferences right in students' homes.

Partnerships and Mentoring

In January 2007, Northrop Grumman Corporation contacted Hillsmere Elementary with an offer of assistance. After meetings with Hillsmere staff to discuss our needs, Northrop Grumman employees have enthusiastically provided physical resources for Robinwood and nurturing relationships for its students. During the summer of 2007, the company financed a complete renovation of the computer lab, Head Start room, and kitchen at the recreation center. Students from Robinwood now have three state-of-the-art community facilities.

In September 2007, Northrup Grumman formed a mentoring program for black boys living in Robinwood who attend Hillsmere. This program seeks to establish meaningful relationships between black men employed by Northrup Grumman and boys who often lack significant male role models. Mentors and boys meet twice a month at the school and sometimes attend field trips or school events together. A key element is the company's recognition that this must be a long-term commitment rather than the kind of short-term outreach poor children sometimes experience, especially around holidays. Beginning in 2008, Northrup Grumman plans to sponsor parenting classes for Robinwood families using the renovated technology room.

Insight Into Poverty

Teachers at Hillsmere, who are mostly white and middle class, have formed study groups to gain a better understanding of the specific needs of students living in poverty. Reading Ruby Payne's A Framework For Understanding Poverty and Glenn Singleton's Courageous Conversations About Race has led to spirited dialogue. These groups create opportunities for staff members to reflect on how their life experiences influence their relationships with students. Insights teachers have gained have helped them make more meaningful connections with students.

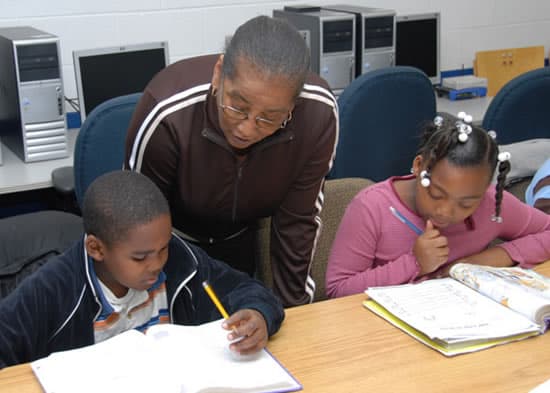

Courtesy of AACPS Schools

Hillsmere Elementary staff members work with students at the Robinwood housing project.

Early Evidence of Success

Although it's too early to gauge the success of Hillsmere's approach, the school has seen a decrease in discipline concerns since the advent of these efforts, with suspensions decreasing from 46 between 2003 and 2005 to 23 between 2005 and 2007. Sixty percent of students who received regular homework help at the recreation center scored proficient on the 2007 Maryland School Assessment. The Anne Arundel County School district encourages other schools to emulate the Hillsmere model and has set a goal to increase partnerships with community organizations. The district now requires all schools to hold at least two activities or meetings in their communities each year.

Schools must respond to the challenge of educating students from poor backgrounds. This responsibility cannot be shrugged off or outsourced. All children can become lifelong learners, if caring people meet them halfway.

Providing Parents with a Comfort Zone

Debbie Swietlik

In 1999, few parents were visible at Annandale Terrace Elementary School in Fairfax County, Virginia. There was neither a volunteer program nor many opportunities for parents to become involved. Today, parents are visible and active all over the school. Why the change? Because Annandale Terrace's teachers and administrators valued the cultural diversity of the school's families and committed energy and resources to getting parents involved.

Annandale Terrace has a student population of 670, with more than 30 different languages spoken at home. Sixty percent of students qualify for free or reduced-price lunch. Approximately 50 percent of are Hispanic, and there are also large numbers of students from Korea, Vietnam, and Middle Eastern and North African countries.

With such a diverse population, teachers knew that increasing parent involvement would be a challenge. So they used Title I funds to create a half-time resource teacher position to strengthen parent involvement, a position I held for six years. The school created a parent center, where parents learn about the school, form relationships, and volunteer. Although this parent center is only one part of Annandale Terrace's comprehensive parent involvement program, it is an essential part, especially for immigrant parents.

Snapshot of the Parent Center

Courtesy of Fairfax County Public Schools, Randy Wyant

Ten to 20 parents a day, many of them recent immigrants, visit Annandale Terrace’s parent center.

The parent center is open daily during school hours. Every day 10 to 20 parents visit, most of them immigrant parents. Many come to see one of the center's four cultural liaisons, who serve the Hispanic, Korean, Farsi, and Vietnamese communities. Liaisons give parents information about the school, provide oral and written translations, and offer emotional support.

The center is comfortable, with coffee brewing and a sofa where parents sit and talk. Shelves hold books with cassette tapes, math games, and dual-language books that parents can borrow to enjoy with their children at home. The school provides three computers for parents' use.

The school's volunteer program is a key element in involving immigrant parents: More than 25 parents now assist regularly in a classroom, the library, the cafeteria, or the art room. Another 50 parents frequently help with office tasks at the parent center. Parent center staff members find a place for any parent who wants to volunteer. Parents can also drop in to the center any time to make learning materials for teachers, who leave instructions and supplies. This enables parents who do not speak English or do not feel comfortable in a classroom to contribute to the school.

The center's Parent Coffees have been essential to developing a core of regulars. Every Friday morning 25 to 30 parents gather for an hour-long presentation on a relevant topic, such as reading instruction or college planning. Translators in the parents' main languages provide simultaneous translations.

These parent regulars became my teachers when I decided to learn more about why parents came to the center and how their attendance affected their children. I surveyed 31 parents who frequent the parent center. I used an open-ended written survey, which the cultural liaisons translated into Spanish, Korean, Vietnamese, and Farsi. Parents wrote responses in their home language, and the liaisons translated. To gain a more in-depth understanding of their responses, I also conducted four oral interviews with parents.

Why Parents Come—and What Happens

I had speculated that parents frequented the center mainly for social reasons. But as I analyzed my data, I realized parents were getting far more than friendship out of their time in the center and that what they were learning there significantly affected their children.

Learning About School and the Parents' Role

Most parents indicated that they came, initially, to learn about the U.S. school system and programs at Annandale Terrace. In the process, parents realized that they play an important role in their children's education. Many families immigrated to the United States primarily so their children could get a good education. But some came from countries in which families are neither welcomed nor valued as partners in schooling. Once they understood that parent involvement is encouraged in the United States, they became active. One commented, I was informed through the parent center how the American school teaches my children. I am constantly learning how parents' influence is important to the children.

Another parent told me that because of what she learned at a Parent Coffee, she now enforces a structured time for homework and limits her child's television viewing.

Cross-Cultural Support

A majority of the regulars said they come to the parent center specifically to speak to a liaison, and most said they would not come if the center were not staffed with a liaison who speaks their language. One parent noted, It's very important to have the guidance of a person who speaks both languages. … The parents have more confidence and trust.

Parent liaisons are the first point of contact for most immigrant parents, and the quality of their outreach is important. They must be compassionate and helpful and establish relationships that help parents feel confident about participating in school.

Parents often stay and talk for hours after the parent coffees, sharing ideas on raising children. Although most parents socialize with others who speak their language, sometimes cultures mix. One Sudanese parent (who speaks English) often joins a group of Hispanic parents making learning materials. Occasionally, the Hispanic parents speak English so the Sudanese mother can join the conversation. At some Parent Coffees, parents present information about their countries and cultures, including sharing distinctive foods.

Courtesy of Fairfax County Public Schools, Randy Wyant

Parents from different cultures work together at the parent center.

Working Together "As Family"

Parent comments indicated how important volunteering is to becoming part of the school community. Almost all parents volunteer occasionally, and many work on projects regularly. Parents say that coming in to help with projects makes them feel productive. If they didn't volunteer, they would be home alone. One parent commented, "In this way, we work together as family."

Immigrant families and families in generational poverty often feel marginalized in school settings by their lack of knowledge and information. When schools help a parent feel accepted and needed by the school community, parents become team members rather than invited guests.

Author's note: Online guides to setting up a parent center are available through the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction (http://dpi.wi.gov/fscp/pdf/fcsprntc.pdf) and the National Network of Partnership Schools ().

The Difference Home Visits Make

Linda Kight Winter and Mark W. Mitchell

It's our job as educators to provide positive school experiences that significantly affect the lives of students. Part of making school experiences significant is connecting them to students' lives—and that requires knowing something of what home is like for students. In our years as administrators in low-income areas, we discovered that setting up ways for teachers to visit students' homes is essential to making that connection.

Linda Winter's Experiences

I administered an alternative high school program for students in Kanawha County School District in West Virginia from 1983 to 2001. The program served up to 1,000 youth who were unable to make it in the county's high schools. Students struggled with circumstances ranging from teen pregnancy to drug addiction: All of them struggled with poverty. Teachers conducted regular home visits to get a feel for the reality of students' lives and, when possible, bring in parents as education partners.

I recall one visit to the home of a student who was frequently late to school. When we arrived at the student's home at the scheduled time, in the late afternoon, we had to knock several times to awaken his mother. As we sat in the living room, I noticed a multitude of prescription bottles on the coffee table. The more we talked, the more I could see that this mother had personal issues which prevented her from providing the support her son needed. Armed with this information, the school gave the student an alarm clock and reported his family's situation to the local protective services agency. This sent a message to both mother and son that we cared about him and would monitor his success in school. I'm not sure whether this student's family life improved dramatically, but his punctuality definitely did.

One high school principal in Kanawha County instituted a powerful way of introducing his teachers to the school's community. This school served many "creeks and hollers" where coal miners and factory workers had lived for generations. At the beginning of the school year, the principal loaded his entire faculty onto a school bus and gave them a guided tour of the attendance area. Because he was a local, during this tour he could make teachers aware of whose father had been disabled in the mines, for example, and which grandmother was raising her grandchildren. This tour revealed to teachers such realities as the long distances between bus stops, the crowding and substandard conditions of many students' homes, and the state of the roads.

Although teachers should not let the kind of information revealed by home visits lower their expectations of students, such glimpses can help teachers understand why a student doesn't have supplies for the science fair, for example, or appears sleepy at school. When teachers know the obstacles many students have to overcome to get to school, they can reach these learners more empathetically.

Mark Mitchell's Experiences

The importance of home visits was clear to me long before I became an educator. As a child, I accompanied my mother, a home economics teacher, on visits to her students' homes throughout our rural area of Missouri. Although the stated purpose of these visits was to check the progress of the students' sewing and canning projects, there was much more involved. Almost all of the families were very poor. By being in their homes and talking with them, my mother could see—and meet—families' needs for books, paper, pencils, and even basic food items. Parents told my mother that without these visits and the relationships they developed with her, many of them would never have come to the school because they would have felt intimidated.

I saw the benefits of outreach firsthand as school superintendent in Neosho, Missouri, a rural area with many Latino students and in which a majority of students received free and reduced-price lunch. Until I retired in 2006, I worked with principals to encourage regular home visits. Home visits became widespread among Neosho's elementary teachers, and parents grew to expect it.

I remember visiting the classroom of one 3rd grade teacher on parent-teacher night at Central Elementary in Neosho. I sensed an excitement in the room and a feeling of community. This teacher had taught this group of 24 students for two consecutive years and visited each of their homes many times. As I watched her interact with the parents, I noticed she knew the names and significant life events of everyone in the family.

Before working with this teacher, only six of these 24 students had tested on grade level in reading and only four on grade level in math. After two years in her class, 19 of them tested on grade level in reading and 20 did so in math. The teacher attributed this improvement to the home-school connection her visits had nurtured: I have a relationship with each of these children and their parents. We have developed trust and communication, and they believe that they have responsibility for and ownership of their children's education.

The Benefits of Home Visits

Home visits were once a staple of public schools. For a variety of reasons—from the shift of schools away from residential neighborhoods to the increase in two-working-parent families—home visits have waned. However, research suggests that such visits would help teachers connect to low-income families. Ninety-two percent of high-poverty parents surveyed in Florida said that home visits would better help them support their children's education (Reglin, 2002). Home visits have been shown to raise achievement for at-risk students in several case studies (Acosta, Keith, & Patin, 1997; Feilor, 2003). We believe schools should revive this practice.