We home-schooled our son Milo after the red, yellow, and green cards became his new identity as a 2nd grader. He was known as "The Boy on Red" and he came home and cried in his closet every night, finally escalating to the point where he screamed, "I just deserve to die. I will always be red. I want to kill myself." — Milo's mother

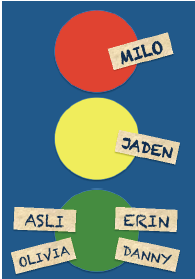

Teachers have the wonderful opportunity to teach a range of diverse learners. This also likely means they must deal with a great range of behavior. To cope with this challenge, educators sometimes use management approaches such as point, sticker, token, or the popular traffic light systems pictured below.

When a student misbehaves, the teacher might tell the student to move the clothespin with his name from green to yellow, or yellow to red indicating to the student—and the rest of the class—that he is not behaving appropriately. Students then receive further consequences such as revocation of recess.

For many well-meaning educators, these systems are intended to reward students for a job well done (green) and to help students stop and think about their behavior (yellow) before it escalates to the point of real trouble (red). However, for students who often end up on red, these systems can have negative, unintended socialemotional consequences. Milo's story above is heartbreaking but in our experience, not uncommon. We have found that student reaction to public behavior systems is nearly always shame, embarrassment, and disconnection from teachers. In fact, these systems increase challenging behavior from the students. Why? The following list highlights the major flaws in public behavior charts:

Students behave for a reason. Students behave to let us know that they are bored, frustrated, angry, hungry, depressed, or embarrassed. Simply moving a student's name on a chart does not address the underlying cause of his behavior.

It is public. Having your name listed next to red indicates to everyone (teachers, volunteers, visitors, and other students) that you are bad. It creates shame, anxiety, and embarrassment. These feelings are not conducive to learning or positive social-emotional growth.

Students are not rewarded. Students on green often feel not rewarded, but superior. If public behavior charts are connected to rewards, it buys short-term compliance, but not the intended intrinsic motivation most teachers seek.

Students with disabilities are at greater risk for being penalized by these systems. Educators are more likely to see students with emotional behavioral disorders, autism, or other behavioral disability labels as misbehaving. The unintended message to the rest of the class is that these students are bad.

It creates lasting scars. In our opening example, Milo's mom shares just how detrimental these public behavior systems can be for a child. Events like this at such a pivotal developmental stage can have a lifelong effect on self-esteem and academic success.

We have both been educators, we have both worked with students with extremely challenging behaviors, and we each now exclusively work with educators—often solving problems related to students with challenging behaviors. We know firsthand that teaching is difficult. In fact, teachers rate behavior as one of the most significant issues they face in schools. We think it is reasonable to want students to follow directions and stay on task to keep the classroom conducive to high levels of learning, especially in this era of accountability. So what might we suggest instead?

Humanistic Behavior Supports

We have several alternatives to the public behavior chart that, when practiced with kindness and compassion, can prove more effective. Using these types of supports can positively change a child's school experience.

Examine the classroom, not the student. Instead of looking for what is wrong with the student, look for what is wrong with the environment. Ask yourself, how can we help this student connect to peers? How can you give her more freedom? How can we create a more joyful learning space? How can he feel more responsibility or ownership?

Be calm and quiet. How can you calm or support a student effectively without drawing undue attention? Can you write a note? Have a private conference? Whisper to her?

Ask the student. Ask what the student needs to be more successful. In this way, we avoid doing things to the student and instead work with the student to determine a solution together.

Increase engagement and fun. Many students are misbehaving because of the nature of a task. Does the complexity of the task match the student's abilities? Can you make it more interesting or challenging? Can it be differentiated? Can you use videos, props, or humor?

Consider sensory needs. Consider your own sensory needs throughout the day. Do you need to dim the lights or stretch your legs to help you calm your mind or body? Students should have these same opportunities. Can you provide students with "fidgets"—small, silent objects with sensory appeal that students can hold in their hands and fidget with? Are there alternate options for seating (pillows, rugs, therapy balls)? Can you provide a physical change such as a dance break?

Sit together. Often when students act out, what they need is someone to hear them. Can you take five minutes to sit with her and let her talk and simply be present?

Be empathetic. Before reacting to the student, consider what it is you need when you feel out of control, bored, angry, upset, or confused. Do you talk with a trusted friend, take a walk, or cry? Providing empathetic, unwavering support for a child in need will communicate that the child belongs and is loved.

Start with love. You are a teacher because you are passionate about education and children. This child is someone's son or daughter, someone's sister, brother, or best friend. Imagine you deeply love this child—react to his behavior with patience, compassion, and acceptance.

When Milo re-entered school the following year, his mom asked the classroom teacher about the behavioral supports that would be used. His mom joyfully reports that Milo is now much happier and more self-assured. He has a positive and nurturing relationship with his teacher. He is no longer "the boy on red." Let's collectively make sure no one else ever is.