To help teachers formulate their own definitions of understanding, I typically ask them about their deepest interest or intellectual passion, something they feel particularly articulate about, are in control of, and are good at. Most teachers are able to define a set of ideas, a theme, or a particular event they say they genuinely understand, not just know about. It is toward such understanding that all teaching should be aimed—toward something students can hold on to beyond the Friday test, the final exam, and school itself.

- Students helped define the content.

- Students had time to wonder and to find a particular direction that interested them.

- Topics had a “strange” quality—something common seen in a new way, evoking a “lingering question.”

- Teachers permitted—even encouraged—different forms of expression and respected students' views.

- Teachers were passionate about their work. The richest activities were those “invented” by the teachers.

- Students created original and public products; they gained some form of “expertness.”

- Students did something—participated in a political action, wrote a letter to the editor, worked with the homeless.

- Students sensed that the results of their work were not predetermined or fully predictable.

So how do we begin to create a classroom that allows for these experiences?

Finding the Overarching Goals

Most teachers begin their planning by asking themselves, What do I most want my students to take away? What do I pay attention to all of the time, come back to again and again? The answers to these questions help form our overarching goals.

Some of these overarching goals may be oriented toward particular skills or habits of mind. For example, among the goals I might set for a secondary school history course are that I want my students to be able to use primary sources, formulate hypotheses and engage in systematic study, be able to handle multiple points of view, be close readers and active writers, and pose and solve problems. At the end of my class, students should be able to develop a historical narrative and understand that history is created by the decisions people make and don't make.

Some goals might be related and recurrent. For example, I would also want students to understand the unfinished nature of American democracy, the ongoing struggle for equity, the connections of past and present, and that each of us is a historian.

I might even put all my goals on the board to assure that my students and I can measure what we do against them. One teacher I have observed who does this regularly asks students to question him about anything they discuss, “What does this have to do with understanding more about ...?”

To help meet my goals, I would make sure that divergent primary sources were available for almost everything we study. Getting materials together would be one of my principal tasks as a teacher. I would also leave room for student choices, for inquiry, for interpretation, for role-playing.

Finding the Essentials

Having outlined goals, I might then consider what content to address within my subject matter by asking, What one topic would I surely pursue? and What two additional topics or concepts must be addressed in this subject area? I could continue this process until I had a fully developed course. In this way I have begun to formulate generative topics—those ideas, themes, and issues that provide the depth and variety of perspective that help students develop significant understandings.

Implicit in the formulation of generative topics is a belief that some ideas have more possibilities for engaging students than others. Democracy and revolution in history, evolution in biology, patterns in math or music, and personal identity in literature are generative topics. Questions of fairness and topics that have recurring qualities (such as immigration) are generative. Slavery has more potential as a generative topic than the military events of the Civil War because its effects are still present. Topics related to technologies are generative because they connect to so many aspects of a culture.

Given my goals in the the history course, I would be likely to have units on the Constitution, the Amendments and the Courts, Civil Rights, Women's Suffrage, and industrialization, as well as units that revolve around patterns of immigration, discrimination, violence, and peacemaking.

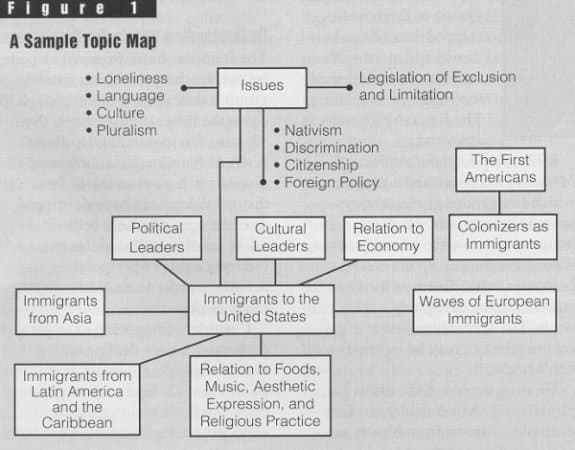

Insights Through Mapping

As a way to think about a topic's generative potential, I would tend to map the topics that emerge from my questioning (See fig. 1). In general, the bigger the map, the richer the topic. After viewing the map, I would focus on some—but not all—of the ideas. The old idea that it is better to pursue fewer topics more deeply has returned to education. For example, the message of The Coalition of Essential Schools that “less is more” is taking hold in more settings. And groups such as the National Research Council of the American Academy of Sciences also recommends that schools focus on fewer topics.

Figure 1. A Sample Topic Map

To choose which of the mapped topics to pursue, I would ask, Which of the topics is most likely to engage my students? Is the topic central to the field of inquiry under study? Is it accessible as well as complex? To the degree that a topic invites questions that students have about the world around them and taps the issues that students confront, it has a generative quality.

“But how,” ask many of the teachers we encounter in our project, “do I interest 28 different students? How do I manage in the face of the unprecedented racial, linguistic, ethnic, and cultural diversity of students?” Mapping the topics provides a graphic representation of the many connecting points within a topic and reveals many different starting points for students. Having a variety of entry points is important for student choice and for engaging students at all levels in work they can honor.

Another concern teachers often raise is how to work within existing district curriculum guides and scope-and-sequence directions. Within a district's scope and sequence, it is possible to generate a topic that engages students' energies and can be pursued with reasonable depth. As an example, a district I know requires a two-week unit on immigration. I can imagine doing the unit using the stories of several individuals, or by studying a single town or a single industry, or by learning family stories across several waves of immigration to see the contrasts and similarities.

In most places, we have found that district guidelines haven't kept teachers from doing what they felt was most important. In an extreme case, several teachers in a southern state with heavy state mandates and tests did understanding-oriented teaching work Monday through Thursday and devoted Friday to what they called “Caesar's work.” Such a path might be worth considering.

A Word on Assessment

For generative topics to help develop students' understanding, ongoing assessment is critical. The 1990s' language of assessment is familiar: authentic assessment, performance assessment, documentation, exhibitions of learning, portfolios, process folios. All of these practices grow from a belief that much that has stood for learning does not get close enough to students' growth, knowledge, and understandings. Assessment activities that do not inform teaching practice day in and day out are misdirected and wasteful, doubly so if they do not help students to regularly make judgments about their own progress as learners.

Movement toward authentic assessment, performance assessment, and portfolios, however, must include serious reappraisal of the instructional program, the organizational structures, and the purposes that guide curriculum. If coverage remains the goal, performance tasks tend to be too limited. If snippets of knowledge dominate the day-to-day activities rather than longer-term projects that produce real works, portfolios become folders of unmanageable paper. If students are not regularly writing across a variety of topics and in a variety of styles for diverse purposes, then promoting self-evaluation has limited value. Further, if students do not have opportunities to complete work they can honor, performance itself loses its importance.

Powerful ideas, powerful curriculum, and different modes of assessment are linked ideas. Without a growing discourse about curriculum purposes, student understandings, and ways teachers can foster student learning, assessment measures such as portfolios and exhibitions will not have a very long or inspiring history.

We need to assure an empowering education for everyone attending our schools. Our students need to be able to use knowledge, not just know about things. Understanding is about making connections among and between things, about deep and not surface knowledge, and about greater complexity, not simplicity. We cannot continue a process of providing a thoughtful, inquiry-oriented education for some and a narrow skills-based, understanding-poor education for most. We obviously have more to do.