Imagine a hotel ballroom filled with teachers and administrators. They listen intently as three primary-level classroom teachers and their principal defend their school's mission, educational goals, assessment tools, and improvement plans. This staff is in the "fishbowl," a simulation activity through which 15 teams are being trained to interview staff, examine documents, and observe schools in Montana's new, voluntary accreditation process.

After nearly an hour of responding to probing questions, the defenders seek advice from their interviewers: How would you approach this problem? Would this assessment tool be useful at your school? Both sides gain new perspectives through the dialogue. Finally, the interviewers unveil a preposterous-looking trophy: the Super Mighty MISTA. The simulation ends with relief, laughter, and applause.

Empowering Schools

Montana Improving Schools Through Accreditation (MISTA) is a pilot program that empowers schools to attain accreditation through their own visions of improved student learning. The process itself is called "Performance-Based Accreditation" (PBA).

Montana is among several states that have tied state accreditation to school improvement. Lauree Harp of the National Study of School Evaluation estimates that nearly 1,000 schools nationwide are engaged in at least one step of a school improvement process tied to regional accreditation. Iowa, for example, has mandated a process similar to Montana's voluntary approach. In Oregon, about 100 schools are involved in the School Improvement Process for regional accreditation with the Northwest Association of Schools and Colleges. The Southern Association of Schools and Colleges is granting accreditation through the Tennessee School Improvement Planning Process, which was mandated by the Tennessee Board of Education.

Montana schools now have the option of either letting their accrediting agency tell them what is best or participating in a process that helps them discover their own ways to improve schools. Because PBA is optional, it may have the advantage of "flourishing in a sandwich," Pascale's (1990) concept of striking the right balance between pressure from below and consensus from above. From the field, Montana felt pressure to develop a more meaningful way to accredit schools, one that considered the quality of programs and processes instead of numbers of students, teachers, and administrators. From the top, PBA represents a consensus among the regional accrediting agency, the state education agency, and the board of education.

But as Michael Fullan (1993) says, "You can't mandate what matters." So Montana agencies are providing professional development to the 18 pilot schools and are turning leadership over to steering committees at each school.

Develop a student/community profile.

Develop a school mission statement that reflects a locally derived philosophy of education.

Identify desired learner results (exit performance standards).

Analyze instructional and organizational effectiveness.

Develop and implement a school improvement plan.

In addition, each school is subject to a comprehensive on-site review. (Using the strategies demonstrated in the "fishbowl," teams are currently conducting on-site visits for one another.)

These five steps transfer the responsibility for accreditation review from the state education agency to school district and community representatives. The required on-site visit goes far beyond a paper-and-pencil report, engaging the school's entire staff and a team of peers. PBA also recognizes that each school's road to improvement may differ. By balancing the five-step process with on-site review, PBA offers both local control and statewide influence.

Launching MISTA

Initially, Montana's accreditation officials feared that PBA would open a floodgate of petitions to waive standards. As anticipated, the first inquiries focused on the last sentence of the standard: "Accredited schools electing this formative process may petition the Board of Public Education to waive existing standards except those that are required by law." Public meetings about performance-based accreditation and the user's manual (Montana Office of Public Instruction 1996) clarified the scope and rigor of the work. Only schools truly committed to improvement and ready to make substantive change joined MISTA.

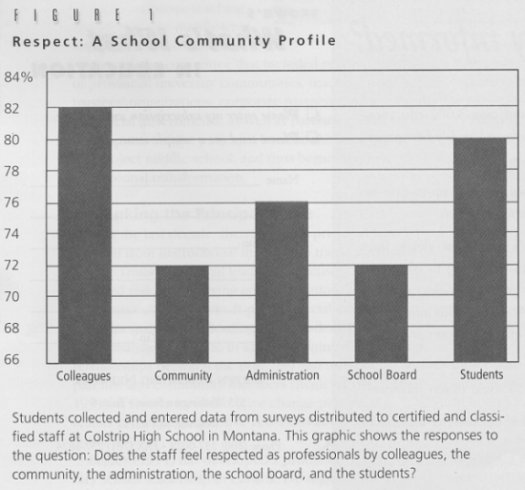

MISTA schools began work in September 1996 with two days of training that focused on how to involve the public, conduct successful meetings, and develop the student/community profile. Participants found that developing a profile of the school and community generated pertinent, concrete, and often surprising information. After three months of work, they also reported a high level of community participation, some frustration with the slow nature of gathering and displaying data, and a new appreciation for the ideas and skills that students can contribute. For example, high school computer students were asked to compile data on the school/community profile and create information displays, giving their work authentic purpose (see fig. 1). The debate about how much data to collect and what is useful still arises, but participants agree on the key criterion: Can we use the information to improve student performance?

Figure 1. Respect: A School Community Profile

Profiling can involve the whole school community. According to Colstrip High School Principal Carol Wicker: Sharing the leadership with people outside your field is often a scary process—for you and for them. About halfway through the profiling step, one of the community representatives observed, "We would never think of allowing community members to come in and help us make decisions in my line of work. But if it worked as well as this has, it certainly would increase community buy-in; and it might make our jobs much easier."

As the profiling continued, MISTA schools held community meetings to explore their values and beliefs, which led to writing or revising their mission statements. These steps were extremely time-consuming, but without them, the schools could not have generated the "accurate picture of reality and compelling picture of the future" that Peter Senge (1990) deems essential to building creative tension and effecting change.

Standards and Strategies

Although state standards may be based on research and public consensus, the state education agency must learn to trust innovation from the local level. As MISTA schools look at current standards, they may be translated into strategies for a school improvement plan. For example, a standard limiting class size in a writing class might become a strategy for achieving the goal of improving students' written communication skills. At MISTA's Billings Senior High, Vice-Principal Barbara Ostrum explains part of the school's improvement plan:Our profiling revealed a general dissatisfaction with student tardies, which were robbing students of learning time. After much discussion, teachers suggested that increased passing time [between classes] in conjunction with not allowing students out of class during the hour [in class] might solve the problem. After a month of using a schedule with passing time increased by three minutes, the overwhelming response from faculty is complete satisfaction. Our teachers are making statements such as, "I'm able to start teaching when the bell rings. Last year I generally had to wait five minutes before I could begin." This effort has improved the climate at Billings Senior. . . . A feeling of hope pervades our school—hope that improvements are possible.

Professional Development

Under older accreditation models, neither regional agencies nor state departments offered much staff development. Training amounted to "orientations" on how to fill out forms and conduct visits. But an accreditation system based on school improvement requires focused professional development to succeed. The 18 MISTA schools shared a total of $25,000 per year from the state; plus they received help from the Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory, which provides about eight days of regional training each year.

MISTA schools have made connections with their communities, strengthened relationships among teachers, and formed a network across schools. The lively discussions that take place within each MISTA school committee are continued and expanded at training sessions. The development of these groups is a key to the change process. To quote Fullan again:[Teacher] isolation is a problem because it imposes a ceiling effect on inquiry and learning. Solutions are limited to the experiences of the individual. For complex change you need many people working insightfully on the solution and committing themselves to concentrated action together (1993, p. 34).

Currently, MISTA schools are analyzing what is preventing them from fully achieving their educational goals. In some cases, this analysis has become a painful experience. Discovering that deep-seated cultural beliefs may create barriers to student success has forced one school to explore new approaches to attendance problems. Teachers at another school believe they aren't meeting the needs of students with different learning styles. Yet another school will experiment with block scheduling in an attempt to foster more project-oriented instructional methods. With the support of information gathered through profiling, a shared mission, and educational goals identified by stakeholders, these groups are "getting to the heart of school improvement" (Sergiovanni 1992).

Studies promoting networking often point out the unfortunate truth "that people in schools don't talk to each other about serious educational matters very much: nuts and bolts—yes; educational issues—no" (Roberts 1992, p. 28). In the MISTA schools, conversations have shifted. At Havre High School, staff members say, "At meetings, we take time to talk about teaching and learning." At Billings Senior, "Discussions at lunch and in the faculty workroom indicate a heightened awareness of a school moving as one toward a goal." Principal Carol Wicker reports:Sometimes the most meaningful by-products of any process or project are not the most visible. As we have worked on our mission statement . . . a vocabulary change has occurred. The staff is understanding the critical tie between what and how they present to the learner and the results we have identified. Those who traditionally taught their content through lecture are saying, "We must become facilitators because there is too much information in the world of the '90s to ever hope to cover it all." . . . Some teachers have even talked of eliminating some of their favorite topics to teach because they cannot see where they fit into our mission with any clarity.

Faculty, students, and parents who devote countless hours to performance-based accreditation are engaged in a rigorous process to do what is right for children. According to Thomas Sergiovanni, people are driven not only by self-interest but also by emotions, values, beliefs, and social bonds. Motivators include "a sense of achievement, recognition for good work, challenging and interesting work, and a sense of relationship on the job" (1992, p. 60). These characteristics of a learning community are evident in the MISTA schools. All share a sense of optimism about the futures they can create.

As MISTA schools move through the next steps of the process, they will be among the first in the nation to earn accreditation through a method that involves an entire school community, focuses on qualitative measures, and is based on an individual school's vision of how to help students reach higher levels of achievement. These schools and their accrediting agencies are rethinking leadership by turning responsibility over to those who see, firsthand, the results of their decisions. As one of the fishbowl participants put it, "We now have teachers actively learning about our school, making decisions about what students are learning and what needs improving. . . . We are empowered."