Six years ago, Frederick County, Maryland, began a major restructuring effort, involving 30,000 students and 46 schools and covering all disciplines and grades. When we decided to become an outcomes-based school system, we could only guess at the impact our undertaking would have upon student learning—to say nothing about our curriculum or our philosophies on teaching and assessment!

The first generation (1988–92) of restructuring involved five components—some were planned and some forced themselves upon us: developing student outcomes, defining curriculum, developing new assessment tasks, planning for instruction, and providing for staff development throughout the process. The good news about restructuring is you can start tomorrow. The bad news is you are never finished.

Our First Steps

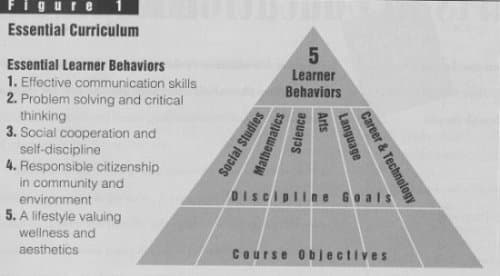

The heart of what we call the “System for Effective Instruction” is a three-part essential curriculum pyramid model that creates objectives for each course, goals for each discipline, and—most important—five integrated learner behaviors that serve as developmental and exit outcomes (see fig. 1).

Figure 1. Essential Curriculum

First, we had to define what Frederick County students should be able to do in each curricular area and how well they should be able to do it. The goal was to align our written, taught, and tested curriculum. At the top of our list was an emphasis on deep understanding and higher-level thinking skills.

- effective communication,

- problem solving and critical thinking,

- social cooperation and self-discipline,

- responsible citizenship in community and environment, and

- a lifestyle that values wellness and aesthetics.

Demonstration of Learning

Next, we had to determine what we would accept as evidence of students' learning. To that end, two of our eight high schools participated in pilot projects to develop student portfolios and senior projects to indicate whether students were, indeed, achieving the essential curriculum.

For example, a senior project to show effective communication might be an oral presentation, a written communication, or a visual display. A student could demonstrate problem-solving and critical thinking skills by defending solutions to real-life problems and situations. The ability to assess self, others, and ideas demonstrates critical thinking skills.

- interview the customer to determine storage needs, cost allowances, and preferred exterior finishes;

- develop a proposal including recommended design, exterior finish, and a basic sketch;

- write a cover letter to your customer summarizing your proposal and explaining why your firm should be hired to do the work.

In each curricular area, essential learner behaviors are supported by essential discipline goals, which, in turn, are supported by essential course objectives. For instance, a task that requires 7th graders to plan a field trip to a museum in Washington, D.C., could meet two essential course objectives: (1) collect, organize, represent, and interpret data and (2) make estimates appropriate to given situations.

These 7th grade objectives support our K–12 mathematics discipline goal: to develop mathematical skills and reasoning abilities needed for problem solving. In addition, the lesson helps students gain skills in effective communication, social cooperation, and citizenship.

Each level and grade of schooling, beginning in kindergarten, uses the foundation of individual courses and disciplines to build toward mastery of the learner behaviors at the top of the pyramid. Integrated essential learner behaviors are important for success in life. No one in the real world stops and says, “Now I am going to do Algebra I, AP Chemistry, or World History.” They just switch gears to accomplish a task.

New and Improved Assessments

What about testing? The ability to fill in the correct answer bubble is not enough for our new curriculum. True mastery requires the ability to apply what has been learned to real-world situations.

For example, an essential course objective in 5th grade language arts is for a student to read or listen to an expository selection in order to process information at the literal, interpretive, and critical levels. Our emphasis was on thoughtful mastery of important tasks, rather than thoughtless knowledge of isolated facts and skills.

Traditionally, because of ease of measurement, our assessment tasks had tended to limit instructional focus to lower-level skills and knowledge. The clear intent of the Frederick County essential curriculum was to reverse this tradition. We determined what was important for students to know and be able to do, and then we decided how to measure it. This system requires the performance of exemplary tasks that reflect the actual performances expected of students.

If we want students to “think with words and think with numbers,” we must emphasize the evaluation of student ability to understand and problem solve. The isolated reading passages and simple word problems found on standardized tests did not meet this need. Routine assessment of prerequisite skills has a place in our criterion-referenced evaluation system, but the relative balance is weighted in favor of critical thinking, problem solving, and communication.

As we began developing activities, we emphasized formative assessment to give teachers a way to monitor student progress on the essential curriculum. We view formative assessments not as teaching to the test, but testing what we teach.

Although initial training, feedback, and review were provided by experts like Grant Wiggins, Frederick County teachers actively developed the assessment tasks. In February 1988, when we invited teachers to apply for summer curriculum/assessment writing workshops, their response was outstanding. As one teacher said, “I don't want someone else telling me what I'll be teaching for the next 10 years.” In designating teachers for the workshops, curriculum specialists sought a balanced representation: experienced and new teachers, males and females, cultural diversity, and a range of instructional levels.

In the spring, acceptance letters went out, emphasizing the importance of the workshops and the work done in them to our school system. Planning for the summer workshops included extensive research and visits and phone calls to school systems already involved in performance-based assessment. Before we began work, we took advantage of several opportunities to plan and confer with consultants.

The Summer Workshops

Two weeks of workshops began with much fanfare that summer. More than 200 teachers from grades K–12 attended. The superintendent and the president of the board of education were there to set the tone and talk about the importance of assessments in our restructured school system. Participants with young children found child care available on the premises. A media specialist provided research materials, and on-site typists at a word processing center turned out finished products.

During the first day or two, several large-group meetings set the framework. Grant Wiggins launched the workshop series by providing an overview of authentic assessment. Then teachers and curriculum specialists worked to translate this broad perspective into real assessments for Frederick County.

We learned a great deal in our earliest workshop. As teachers created assessment tasks, their efforts touched other curriculum areas and grade levels. What developed was something unexpected and exciting—a common educational focus! However rosy a picture we paint, we admit that writing these first assessment tasks was a struggle. Teachers worked diligently to write the assessments, only to find that they were uninteresting to students, or that they did not test what we wanted them to test.

Finally, at the end of the first two-week workshop, the assessments began to jell. And when the workshops ended, each curricular area had several assessments to pilot.

As teachers were writing assessment tasks, they were also developing scoring systems for student performance at various levels. After debating the merits of different frameworks, we finally decided to use four-point rubrics for continuity across schools, grades, and disciplines. While specific rubrics are written for narrative writing, problem solving, and reading comprehension, for example, all use the same framework:

Moving from Seat Time to Mastery: One District's System - chart

4 = exemplary (fully meets criteria)

3 = proficient (adequately meets criteria)

————Mastery Line————

2 = approaching proficiency (sometimes meets criteria)

1 = evidence of attempt (seldom meets criteria)

The four points are not equivalent to letter grades. They are a method of assessing the degree of proficiency exhibited in a student's response to an assessment task. The goal is to have all students progress to the point of mastery, with the teacher functioning in the role of a coach.

Our goal for the initial year was to pilot assessments in language arts and math in grades K–8. Eventually we hope to develop essential curriculum and assessment tasks in every area. To date, we have accomplished this in language arts, math, science, social studies, art, music, physical education, and business education.

Selection of “Anchor Papers”

Once the teachers had completed their work on assessments during the workshops, our curriculum specialists spent the remainder of the summer finalizing the tasks and planning teacher training. During a day of inservice before schools opened, the curriculum specialists met with teachers in their curricular areas and presented overviews of performance-based assessments, discussed the importance of formative assessments, and illustrated tasks that had been written during the summer.

Teachers in the pilot schools worked closely with the curriculum specialists to collect examples of student work. These examples, called anchor papers, provided consistency in evaluating student work and gave us samples of mastery, as well as every other point on the rubric.

The selection of anchor papers took place at a number of painful meetings during the first four months of school. Selection was the result of serious debate, which made us look at what the standards for mastery were. For example, teachers asked, “Is this what we want the writings of a 3rd grader to look like?” or “What needs to be in a response that shows mastery?” It was very difficult to look only at responses and not focus on the effort of the student.

By looking at the anchor papers, we found that teachers could learn how to adjust instruction. After piloting the assessments and agreeing on the anchors that best illustrated the standards, we faced the task of inservicing all the other teachers! The only way we could accomplish this awesome task was to use a “trainer of trainers” model. In elementary schools, the language arts curriculum specialist met with the reading specialists and developed a training module on assessment. Each reading specialist took the module and used it as the basis for staff development in his or her school.

Variations on this procedure were used in every curricular area. Sometimes curriculum specialists worked with department chairs, team leaders, or assistant principals. These people, in turn, worked with the teachers. Of course, curriculum specialists, our testing supervisor, and staff development facilitators were available for assistance.

- write the curriculum and assessment;

- pilot the curriculum and assessment in selected schools;

- refine and adjust the curriculum and assessment;

- provide inservice for all teachers; and

- adjust, refine, and rewrite.

Improvement as a System

Next we began to develop summative evaluations, using the same procedures used to write essential curriculum and formative assessments. The formats of formative assessments and rubrics are similar to those used in the summative evaluations. However, the summative evaluation gives the school and the school system information about how groups of students, rather than individual students, are achieving. This information helps us adjust as a system. If students do poorly in 3rd grade mathematics across the school system, we know we need to analyze our curriculum, instruction, and/or assessment procedures. Formative assessment helps us adjust for a student; summative assessment helps us adjust as a system.

In our school system, yearly progress reports are published so that our public can view the results of these assessments. Our community is informed each August of the percent of students who have mastered the essential curriculum, with the results disaggregated by gender, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status.

Teachers in different classrooms and schools must agree on the performance standards for students. Samples of student responses to the summative assessments are selected from a variety of schools so that teachers can “anchor” their evaluations of student work. The published set of anchor performances is available to all teachers in all schools, and yearly “checks” of scoring consistency help us to adjust staff development programs.

What We've Learned

After six years of hard work, we realize the key role staff development plays in the restructuring process. Teachers need to learn how to assess students' knowledge and also how to teach the higher-level behaviors required by the performance tasks. Performance-based assessment requires students to perform at a higher level than do multiple-choice assessments. The change from multiple-choice testing to teaching that emphasizes problem solving and higher-order thinking cannot be assumed. It must be planned.

Another lesson is that the development and scoring of assessments is labor-intensive. Time is needed to write assessment tasks and to train teachers how to give and score them. We have found it very profitable to combine resources with other districts in order to develop assessments and share training of staff. During the summer of 1991, 16 Maryland school districts worked together to develop assessments, rubrics, and anchors for language arts, mathematics, science, and social studies in grades K–8. The result was three volumes of assessments, which would have taken each of us years to develop! The assessments are now part of a computerized database, which is accessible to the staff upon request. The Maryland Assessment Consortium, an ongoing entity, represents all 24 Maryland school districts.

While much attention has been given to the written curriculum and assessments, if assessment is to increase learning, it must be directly integrated into daily teaching. Only when teachers learn to analyze the assessments will they be able to coach students in the higher-level behaviors.

What Lies Ahead

The second generation (1992–97) of our restructuring process is already under way. A videotape and accompanying brochure have been provided to all schools to assist parents and the community in understanding “Teaching and Testing for the 21st Century.”

The original design of the System for Effective Instruction emphasized building the foundation of the essential curriculum pyramid. The second generation will focus more directly on the original reason for moving from seat time to mastery: ensuring that all students reach high standards of understanding and application. Developmental and exit portfolios will eventually provide the evidence of integrated mastery required for success as productive adults and lifelong learners.