Weld County School District 6 serves the cities of Greeley and Evans, Colorado, some 55 miles north of Denver. The cities' combined population of 60,000 includes large numbers of both affluent and very poor residents, reflecting trends nationwide.

The majority of low-income families are Hispanic (especially Mexican), many of whom are migrant laborers. Of the 13,500 students in grades Pre/K–12, about 65 percent are Anglo, 33 percent Hispanic, and 2 percent other. As in communities across the country, the number of disadvantaged children is growing much more rapidly than the population of affluent children, irrespective of race or ethnic background. And, as in many American communities, there has been an alarming learning gap between the two groups of children.

In 1987, District 6 decided to do something about these educational disparities. We began a major school reform effort that was centered on redesigning our assessment system. Our aim was not just to narrow the learning gap, but also to improve the academic achievement of every child.

In the next school year, we introduced a system that is based, not on grade levels, but on evaluations at various junctures in a student's schooling. Before students can proceed to the next level (for example, middle school), they must demonstrate their mastery of certain concepts and skills in writing, reading, and mathematics that are important for everyone to know. In short, it is no longer acceptable to send students from one level of the system to the next knowing they have not met minimum standards.

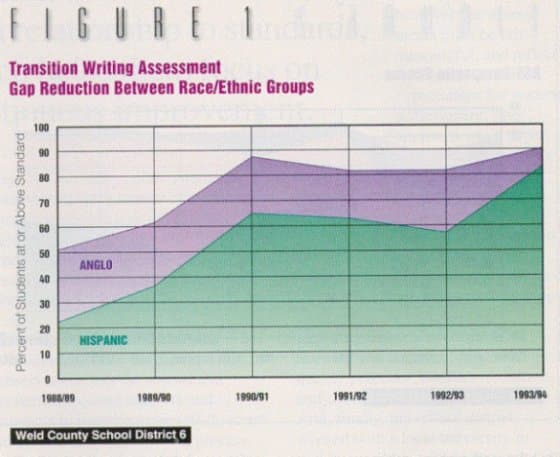

The results of our transition assessments have been impressive for every student population. The achievement gap between Anglo and Hispanic scores has decreased dramatically, while the performance of both groups has improved (see fig. 1). And this has occurred while the number and percentage of Hispanic students has increased. Our data demonstrate that it is indeed possible to achieve equity of education for all our children, without sacrificing educational quality.

Figure 1. Transition Writing Assessment / Gap Reduction Between Race/Ethnic Groups

Back to the Drawing Board

Our school reform effort began in earnest during the 1988–89 school year. We launched a strategic planning process that involved not only teachers and administrators, but also parents, students, business-people, and other community members. We believed that for a reform of this magnitude to be effective, all segments of the community had to be involved.

The Board of Education's adoption of the strategic plan triggered a great deal of activity over the next six years, all of which affected student performance. School District 6 became increasingly decentralized in decision-making; developed partnerships with the business community; and worked with community-based agencies, private organizations, and individuals to better coordinate the delivery of services needed by low-income families and children at risk.

Setting Standards

- We identified important concepts and skills that all students should know or be able to do to be well prepared for their lives after high school.

- We formed an advisory council of area employers to make sure the skills we identified were essential for successful employment in area businesses.

- We established performance criteria and standards that a range of groups accepted as evidence that graduates are well prepared.

We also identified a strategic objective—the expectation that all students would meet or exceed these standards by 1995, regardless of ethnicity, socioeconomic status, or gender.

Reading, Writing and Arithmetic

- [[[[[ **** LIST ITEM IGNORED **** ]]]]]

- The story and information components of the Essential Skills Reading Assessment (Michigan State Board of Education 1991). This test provides information about how well students construct meaning from fictional (story) and non-fictional (informative) material. The test is in multiple-choice format with long passages from well-known authors.

- The Essential Skills Mathematics Test (Michigan State Board of Education 1991). This test measures students' understanding of mathematics content (numeration, fractions, measurement, geometry, problem-solving), and students' proficiency in mathematical processes (conceptualization, computation, application, and computers). Even though a machine-scoreable multiple-choice format is used, our analysis indicated that the objectives tested were congruent with the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM) standards.

On each of these transition assessments, students receive one of four performance ratings: 4 - Advanced (superior); 3 - proficient (excellent); 2 - Essential (very good); 1 - In Progress (needs more instruction).

Rethinking Assessment

- The system must not be based on age or grade level, but on demonstrated performance at selected transition points. Students are required to demonstrate mastery of content, concepts, and skills on a transition assessment before they move from elementary to middle school, from middle school to junior high, from junior high to high school, and before they graduate from high school.

- The system must reflect what we know about the variability in learning rates among students. That is, it must enable students to demonstrate that they have mastered required content, concepts, and skills when they are ready, rather than waiting until the traditional end-of-the-year testing period. If students sometimes need more than one opportunity to demonstrate successful learning, the system must accommodate this need. The highest priority is to assure that all students meet standards before moving to another level.

- The system must immediately relay assessment scores to students and teachers. This real-time data allows early and continuous improvements in the instructional process.

- The information on student achievement must be disaggregated across student subgroups. In other words, assessment reports contain graphs that reflect differences in achievement between boys and girls, Hispanic and Anglo students, and students from families of different socioeconomic levels (we use the mother's educational level as a proxy variable). This is done because huge disparities in student performance are common to all school systems, but it is only when test data are disaggregated that the staff and the public see the magnitude of the disparity. (The initial disaggregated data was a shock to everyone in District 6!)

- Instruments must measure student performance in relation to a standard rather than compare students to other students or to a national norm.

- Student performance on our new standards-based instruments must correlate with an acceptable standardized, norm-referenced test. This is necessary to determine the effect our curriculum and instruction are having on district students in comparison to their counterparts across the country.

This last provision made it possible for us to obtain a waiver from the State Board of Education's standardized testing program. Colorado requires all students in grades 4, 7, and 10 to be tested on a standardized norm-referenced test at a specified time each year. In lieu of this test, we conduct a study linking our standards-based transition assessments to norm-referenced data on the Comprehensive Tests of Basic Skills, 4th Edition (see Burger and Burger 1994).

High Marks for the New System

Since the introduction of the standards-based measures for writing, reading, and mathematics, there has been a dramatic increase in the percentage of students who have met or exceeded the performance standards (the Essential level or higher) in each assessment area.

In 1991–92 and 1992–93, there was a slight decrease, which we believe was a consequence of introducing the new reading test. As teachers concentrated on reading skills, they paid less attention to writing skills than they had in previous years. Performance on the reading assessment improved dramatically in 1991–92, however, and again in 1992–93.

In 1992–93, the new math tests were introduced. Although they, too, required additional time and attention of teachers, we were better prepared this time and so did not lose our focus on writing and reading. By 1993–94, both teachers and students were familiar with the standards and the expectations of the reading, writing, and math assessments.

Overall, our progress has been encouraging and exciting. Each year, more and more students are moving to the next level with the skills required to be successful. Teachers report that new classes of students are better prepared than ever. And as student performance continues to improve, teachers expect more of all students.

Narrowing the Gap

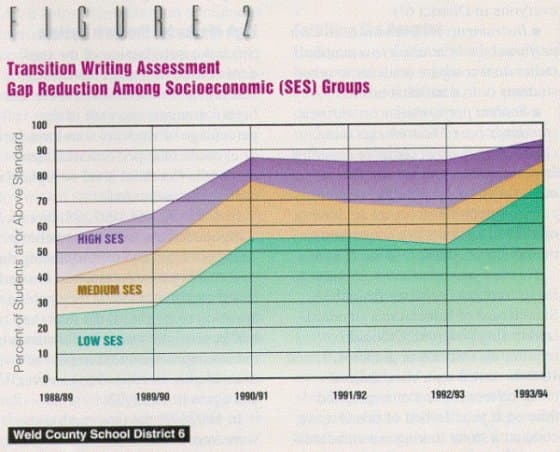

Figure 2 presents a promising picture of across-the-board strides in writing. As mentioned earlier, we have based socioeconomic status (SES) on the mother's level of education. Research and our data reveal that socioeconomic status is a more powerful predictor of achievement than race and ethnicity, and students coming from low SES homes present the greatest educational challenge.

Figure 2. Transition Writing Assessment / Gap Reduction Among Socioeconomic (SES) Groups

Mothers of low SES group students have had no formal education or have not gone beyond elementary school, mothers of medium SES group students have gone beyond elementary school but not beyond high school, and mothers of high SES group students have gone beyond high school.

Both Figures 1 and 2 show that while student performance improved significantly within one school year of implementing the standards-based writing assessment, the gaps among ethnic and socioeconomic groups were most markedly reduced in 1993–94. That year the district took an important step in providing achievement data to teachers and students within two weeks of the assessment. The results enabled teachers to make timely decisions about preparing students to go beyond the district's Essential standard.

Also in 1993–94, we increased the frequency of assessment tests from four times a year to once a month (in 1988 frequency had been increased from once a year). Students may, however, elect to pass up the scheduled test or take it over again if and when they and the teacher decide they are ready to demonstrate mastery of the content, concepts, and skills.

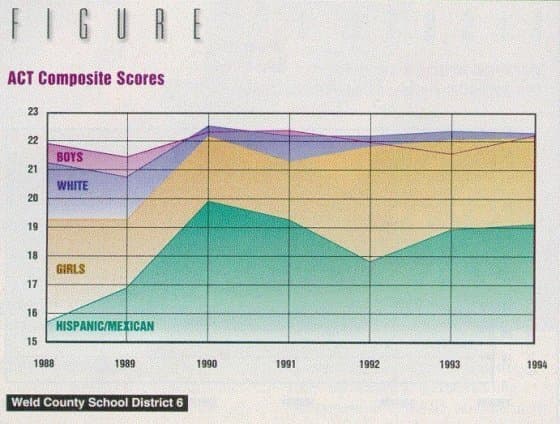

The improved achievement on the district's transition assessments is also reflected in American College Test Composite (ACT) scores. Since the transition assessments were implemented, the ACT composite score has increased, with a decrease in the gap between Anglo and Hispanic students, and also between boys and girls (see fig. 3). Currently, we are unable to analyze the ACT results by socioeconomic status because too few low SES group students take the test. Still, since the transition assessments began, the number of Hispanic students taking the test has tripled.

Figure 3. ACT Composite Scores

Spurring Teaching and Learning

We conclude from the data and our observations that the assessment system empowers teachers and students to become more self-directed in the teaching and learning process.

Students know exactly what is expected of them and where they stand in relationship to standards, which helps them focus on continuous improvement. Teachers get accurate feedback on their instruction, and they know what each student needs to do to meet or exceed the next standard. In other words, they can base teaching decisions on solid data rather than on assumptions, and they can make adjustments early on to avoid the downward spiral of remediation.

In addition, once the standards were established, teachers and administrators developed procedures to provide the kind of quality instruction that would enable students to meet them. In our view, this is why high standards and effective assessment are central to quality curriculums and instruction. Effective assessment not only certifies individual student performance in relation to a set of standards, but motivates students and teachers to meet those standards.

For this to happen, however, the assessments must be fair, meaningful, and reflect the highest possible expectations for student achievement. This approach was a departure from our district's existing method of measuring and reporting accountability data, which had little impact on instruction.

Further, teachers must be prepared for the new system. During our strategic planning phase, we provided teachers with extensive staff development and inservice programs, including training in cooperative learning and team building, total quality practices, conflict resolution, and coaching for high performance. And, finally, the school district worked with a local university to design programs to prepare new teachers for the classrooms of the 1990s.

Fulfilling the Promise

Recognition of educational disparities has spurred many of the reforms that schools, school districts, and state departments of education are now undertaking. America's system of public education, with its promise of equal educational opportunities for all, regardless of family circumstances or income, is a product of one of the greatest social experiments in history. The system, unfortunately, has not delivered on its promises.

As the movement to reform America's schools moves into its second decade, many critics bemoan our inability to make the changes necessary to yield significant, sustainable improvement in student achievement. Our data show that it is possible, but it is not simple. It takes time and thoughtful effort on the part of school board members, teachers, administrators, parents, and students.

Our results should say something to state legislatures, state education departments, school boards, and federal agencies that fund and direct reform efforts: Your investments are warranted. If we are successful at aligning curriculum, instruction, and assessment with professional development, we can deliver on a promise to America's children that is long overdue.