Two elementary schools. Two very different student populations. What would happen the following year when the 6th graders attended the same middle school?

Stereotypes had already contributed to reluctance on the part of some parents to enroll their children at Mansfeld Middle School in Tucson, Arizona. In fact, only 20 percent of 6th graders from Sam Hughes Elementary School attended Mansfeld last year. Students at Richey School have experienced assimilation difficulties contributing to a nearly 90 percent high school dropout rate. In addition, teachers at all three schools had heard, first- or secondhand, of students making derogatory comments and racial slurs.

With two of her own children at Sam Hughes, Alisa Z. Shorr—a staff member of Arts Genesis Inc., a community-based arts education organization—-knew something about sources of conflict between the two schools. One is the family income disparity. At Sam Hughes, only 22 percent of students are eligible for free lunches, while at Richey School over 90 percent of neighborhood students qualify.

Ethnic makeup in the schools also varies dramatically. Seventy percent of Sam Hughes students are Caucasian, and 23 percent are Hispanic. At Richey School, the population is almost equally divided between Hispanics and Native Americans (almost all Yaqui Indians), with the remaining 6 percent a mix of Caucasians, African Americans, and Asian Americans.

Shorr had long been thinking about creative ways to change stereotypes held by parents and children attending the two schools. At the same time, eager to help their students cope with the upcoming school change, two 6th grade classroom teachers—Pat Larson at Richey and Haven Force at Sam Hughes—wanted to teach conflict prevention and resolution strategies to their pupils through a real-world experience.

Shorr approached Arts Genesis Executive Director Carol S. Kestler. Kestler worked with Shorr, the classroom teachers, the school principals, professional artists, and a conflict resolution specialist to find a way to use creativity to expose the common bonds shared by children from both schools and their families.

During the spring of 1995, 60 6th grade children from the two diverse communities participated in "New Beginnings," a poetry and visual arts project of Arts Genesis. Through their interactions with one another, the children created a basis for understanding, compassion, and trust.

Why Involve the Arts?

Although, traditionally, art instruction in schools has focused on developing the individual student's creativity, it isn't that way at Arts Genesis. Over the last 15 years, a portion of all of the organization's school programming has involved collaborative artwork and writing. "Art involves exchange, dialogue, and communal values," says Kestler. "What better way to experience cooperation and develop communication and conflict resolution skills than by creating art collaboratively?"

In addition, unlike teamwork in sports, collaboration in the arts is noncompetitive and nonhierarchical. Doing artistic work also develops children's critical thinking skills, says Charles Fowler: "Instead of telling [students] what to think, the arts engage the minds of students to sort out their own reactions and articulate them through the medium at hand."

New Beginnings brought an experienced conflict resolution facilitator into each stage of the project so that both students and staff at the two schools focused on ways to make the meetings between the children peaceful and instructive. At all stages of the process, the children learned ways to respect and cope with individual disagreements as well as cultural differences.

Arts Genesis drew on its five-year collaborative partnership with Phyllis Kietha Gagnier, a conflict resolution facilitator with 20 years' experience in Arizona schools. In January 1995, Gagnier provided training for the project staff (including artists, writers, school principals, and classroom teachers) and helped plan the project, including the publication and celebration of a jointly created book. The Arts Genesis staff decided the best way that New Beginnings could address the special needs of these children would be to help them and, in the final meeting, their families to share deep feelings and important issues in a respectful and creative environment. New Beginnings had begun to take shape.

Crossing Barriers

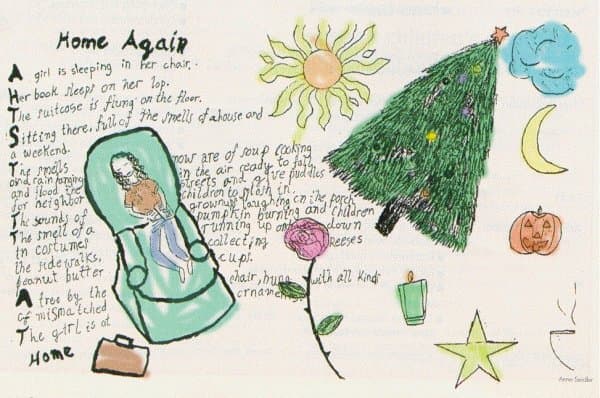

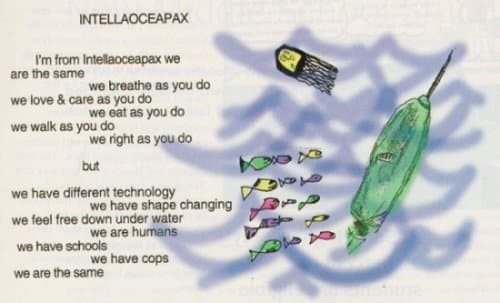

In February and early March, students, in their separate classrooms, wrote and illustrated poems about people and places they loved and about deeply felt experiences. They did this under the direction of four professional writers and two visual artists. The arts educators helped students with both literal and nonliteral ways of capturing, in images, the essence of a poem. Classroom teachers Force and Larson spent considerable in-class and after-school time assisting students during the project, helping them write, illustrate, and print final copies of their poems from the schools' computers.

In March, students from both elementary schools came together at Mansfeld Middle School. After settling into the teacher-selected, mixed-school groups of six, the children introduced themselves. Group facilitators helped the children feel comfortable sharing their work. Indeed, it isn't always easy for published adult writers and artists to show their work to strangers.

Led by award-winning fiction writer Kit McIlroy, one group of children read poems and shared illustrations. They discussed a poem by a child who was obviously angry about a family incident. McIlroy told the students that writers sometimes describe things that are difficult for people to hear.

The feelings expressed in the students' poems—both positive and negative—were open for discussion. The poems illuminated similarities in their lives—a common bond, despite their differences.

Among the many barriers crossed on that day was language. In poet Laura Bean's group, two students read their poems in Spanish. After each presentation, the children were asked to pick words they remembered from both the English and Spanish poems.

"The English-only students really got into the sounds of Spanish words, and could talk about why they had remembered them," says Bean. Children who had written in Spanish felt proud when the other children asked them what certain words meant. A non-Spanish speaking Hispanic girl in Bean's group found that she knew the meaning of many Spanish words in other children's poems. Elsewhere, throughout the morning, language differences became a source of interest among the children instead of a reason for distrust.

Figure

Figure

Figure

Learning to Collaborate

The final event of the morning—collaborative writing and art-making—gave students a taste of working together on a small project as a precursor to the larger book they would also create together. Members of each group decided how they would collaborate and what their creation would look like—for example, a group drawing or a group poem. Others took words or phrases from their individual pieces and wove them together into a larger collaborative work.

In Kestler's group, students began by discussing how they personally related to the poems they'd heard. Then, each student borrowed a phrase from someone else's poem—an adjective and a noun, such as "special friendship"—and wrote a paragraph-long story using these phrases. Later, the children collaborated on a group drawing. "The boys chose sports images, which the girls called 'dumb,' and the girls chose flower and heart iconography, which the boys called 'silly,' " explained Kestler. When she asked them to build on each other's images, they produced a large collage of words and graphics that reframed the smaller images in flowing borders and landscapes they all felt proud of. Kestler and other facilitators relied on the problem solving and collaboration inherent in art production to teach children how to get along despite differences.

After completing the projects, representatives from each group read the collaborative pieces and held up the cooperatively created artwork for everyone to view.

That afternoon, when the children returned to their classrooms, both teachers felt the need to debrief them on their experience. Students wrote down their observations and then discussed their feelings—both good and bad. For example, one Richey student was uncomfortable because his spelling had been repeatedly corrected by a Sam Hughes student. The class talked about dealing with uncomfortable feelings. Then the students named some of the life skills they had used during the day, including patience, courage, cooperation, and respect for one another. Many students had come back with new perceptions about their peers at the other school.

Creating a Common Work

The first meeting at Mansfeld demonstrated the natural companionship that arises when children meet in a well-prepared, safe environment. New Beginnings put this same preparation into the production of the collaborative book.

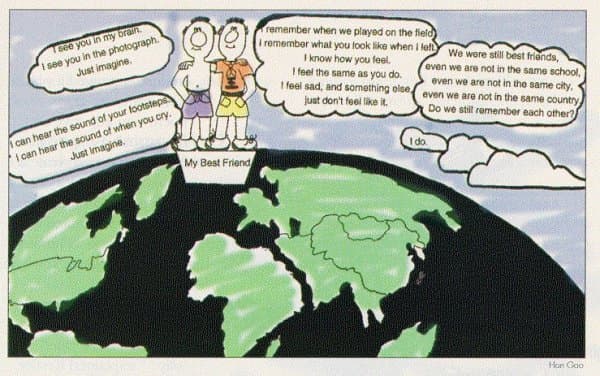

In subsequent weeks, the students arranged the individual poems by themes that they chose: "We Are All Poems," "I Am Watching," and "Do We Still Remember Each Other?" Each student designed his or her own page with words and visual images. A vanload of volunteers from the two schools visited the printer to see their book on the press and then told their classmates about the experience.

The same care went into planning the final meeting to celebrate the book's publication. Students from the two schools met and designed decorations, including displays of their collaborative work completed at the first meeting. Parents prepared and served food. Students read their poetry aloud, autographed one another's books, and showed the mounted originals of their drawings to one another and their parents.

After the project concluded, Arts Genesis staff interviewed the children to determine its effects on them. Their comments reveal positive benefits from the program. "At first you were just with your own crowd," said a girl from Sam Hughes School, "but then you got to feeling kind of open and together, like we were all a group, because everyone shared a common thread."When asked what the common thread was, she said, "Everyone was nervous.... We all realized that everyone else was just as nervous as we were."

A girl from Richey School talked about getting to know Sam Hughes students just through talking: "We had a lot of stuff in common. We had nicknames, and we were the shortest ones in our classes, and the weirdest and the funniest.... I can't wait to go over there again."

When asked about meeting students from the "other school," Joe, a white 6th grader from Sam Hughes, said, "I made a friend, Steven [a Yaqui Indian]. He wrote a poem about eagles, and it goes like this." Joe then recited the entire poem from memory.

More New Beginnings

New Beginnings helped students develop social skills they will need when they enter middle school. Many of the students told the interviewer that they rarely met students their age except in their own classrooms, which explains some of the difficulty they have merging at a new school.

Children's expectations for conflict were also challenged. Although minimal violence occurs at Mansfeld, some students had heard otherwise. A Sam Hughes School student learned that "there's not as much gangs as what they talk about, just people."

The ultimate outcome of conflict prevention programs is difficult to measure. In objective, scientific terms, success cannot be assessed unless the staff studies how Sam Hughes and Richey students actually relate to one another at Mansfeld Middle School compared with peers who have not shared this experience.

The goal of New Beginnings, however, was to provide interaction among children that elicited deep feelings and gave them ways to express those feelings productively. Conflict resolution specialist Gagnier observed that participants gained "the perception that their work and their person is valuable to others beyond their classroom teacher." This boost in self-esteem can only help children better address conflict as they mature.

The New Beginnings project addressed, simply and directly, a special need in a diverse community. Because deeply felt experiences and beliefs were the source of much of their writing and art, New Beginnings helped the participants value their unique experiences and those of others from different backgrounds.