As conscientious scientists we simply cannot hide from the public the following bitter truth: All that politicians, journalists, educators, and others have told you about the social benefits of education and self-development is pure ideology devoid of empirical foundation. In reality, our achievements are directly dependent on the level of our intelligence, as measured by IQ tests, and largely predetermined genetically.

Those with a higher IQ will move faster up the social ladder, while those with a lower IQ will slide down. This dynamic is an objective fact of nature.

There is little sense in pouring our tax dollars into remedial educational or social rehabilitation programs, because their influence on IQ levels is very limited.

However, you, dear readers, should not worry, because the very fact that you are reading this $40 volume is a clear sign of your high IQ and thus a guarantee of your social success (statistically speaking).

There is nothing particularly new in this position. It largely repeats the notorious thesis of educational psychologist Arthur Jensen: Intelligence is distributed unequally among races and is resistant to change. This viewpoint led Jensen to suggest curtailing all intervention programs, such as Head Start, and instead using simple repetitive exercises, orienting these children's education to what he referred to as Level I intelligence (Jensen and Inouye 1980).

Such conclusions so clearly fly in the face of scientific data and common sense that one might dismiss The Bell Curve as having no value whatsoever. And yet, the book does. It presents ideas and information that are both relevant and interesting, although some of its main claims are extremely misleading.

The Ring of Truth

A general emphasis on cognition as an important factor in human performance and social achievement. All too often, human performance is presented either as a purely behavioral phenomenon or as a product of emotional and affective conditions and unconscious motives. The Bell Curve appropriately points to cognition and intelligence as a major force mediating human behavior and social conditions. Unfortunately, this strong emphasis on cognition leads to some faulty conclusions. This happens because the authors chose to reduce intelligence to the IQ score, which they consider immutable, stable, and resistant to change, whether by education, development, or rehabilitation.

The notion of human diversity. The modern world is becoming homogeneous in the more basic everyday activities. Yet people, fortunately, continue to exhibit very different cognitive operations, abilities, and styles. It is one thing to acknowledge that certain aspects of cognitive functioning are genetically linked, and quite another to claim that these characteristics are unalterable. Further, certain ethnic, cultural, and racial groups may display characteristic patterns of cognitive functions that are statistically distinguishable. But this does not imply that these groups can be plotted in a linear way from less intelligent to more intelligent, as argued in The Bell Curve.Height is one aspect of human diversity that is transmitted genetically from generation to generation. And certain ethnic groups, such as the Japanese, are statistically shorter than other groups, such as the Dutch. At the same time, height is also a changeable characteristic, as evidenced by the rapid increase in the height of the Japanese in the second half of the 20th century. Chromosomes do not have the last word, even in the case of highly heritable characteristics.

A very interesting, though somewhat frightening, portrait of contemporary American society. The Bell Curve pictures this society as being capable of reducing the most complex phenomenon—human intelligence—to arithmetic and word memory tasks, then building a whole industry of evaluation, selection, labeling, and promotion on this primitive foundation.

This is a society in which 5 percent of those with higher than average intelligence, together with 6 percent of those born to rich and very rich parents, are destined to live below the poverty line. Apparently neither your IQ nor the social status of your parents can guarantee you decent living standards in the United States.

Intelligence as a Thing

Most important among The Bell Curve's misleading claims is the contention that intelligence is a measurable substance and the IQ test is a reliable measuring device. This claim sets us back more than 50 years, ignoring all the achievements of cognitive and developmental psychology in the last half of the 20th century. The fact that some manifestations of intelligence can be measured does not imply that intelligence itself is a stable substance. To present intelligence in this reified way—as a concrete, stable quantity—is a scientific anachronism.

Intelligence is a propensity, a tendency, or the power of the organism to change itself to adapt to a new situation. It is multidimensional and modifiable, the very qualities that have enabled humans to adapt so effectively to a multitude of environments. Only if one accepts the reified version of intelligence can one believe in its deterministic predictability.

The realization of intellectual power is dependent on a great variety of biological, social, and cultural variables. It may vary from individual to individual, depending on factors such as genetic endowment; prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal development; and so on. It is important to understand that we never observe this intelligence as a power directly, only through its various realizations.

Infallibility of IQ Tests

Human intelligence is so extraordinarily complex that we have been forced to expand our research approaches rather than reduce them. Unfortunately, the authors of The Bell Curve chose an extremely reductionist position, equating the assessment of intelligence with the IQ measurement.

Herrnstein and Murray's far-reaching conclusions are based on the following: First, intelligence is equated with test performance. Then the whole range of possible tests is reduced to a few knowledge-based tasks performed in a limited time period. Finally, the data obtained are interpreted far beyond their actual empirical base.

The authors rely on data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, which is based on a large sample of young people aged 14–22 when the study began in 1979. As a measure of IQ, the researchers used four subtests of the Armed Forces Qualification Test: word knowledge, paragraph comprehension, arithmetic reasoning, and mathematical knowledge.

There is little doubt that we can measure the number of words recognized or mathematical operations accurately performed, but by doing so, are we measuring intelligence? How is it possible to claim that IQ measured in this way is unaffected by education? In reality, the results of IQ testing are so compounded and contaminated by various processes that it is impossible to distinguish which part reflects intelligence as a power and which reflects various irrelevant conditions. In The Bell Curve, excessive reliance on statistical correlations without proper analysis of the data creates a statistical mirage, presented to readers as fact.

There are sufficient data to suggest that IQ test scores reflect not only—even probably not so much—the central thinking capacities as the individual's ability to decode test items and respond in an expected way. The elaboration phase of cognition is traditionally associated with intelligence as such. Yet many low IQ scores result from specific problems during the perception (input) phase or response (output) phase. Slow information processing may also be interpreted as a failure of intelligence. Some studies of twins indicate that speed of information processing is a highly heritable characteristic. Thus, although results of tests taken under tight time constraints may appear to indicate a similar IQ, they may in fact merely reflect a similar speed of processing.

Culture and Intelligence

More than half a century ago, Lev Vygotsky identified two major lines in the development of human intelligence: natural and cultural. In the course of a child's development, the natural forms of intelligence—including perceptual abilities, memory, attention, and problem solving—are structurally changed by the cultural tools society associates with literacy and education (Kozulin 1990).

Feuerstein's theory of mediated learning experience (1990) attributes people's differing capacities for modifiability to the unequal amount and type of mediated learning they have experienced. These capacities (or levels) are, however, dynamic; remediation in mediated learning can change the extent to which someone's cognitive level can be modified.

The paradox of IQ testing is that while it is strongly culturally embedded—problem solving depends on certain symbolic and representational systems—its results are interpreted in terms of natural intelligence. Testing situations are also culturally constructed: test items, modalities of presentation and response, time limitations—all these may affect test results in a variety of ways. Yet, instead of interpreting the results as an outcome of interaction between the individual and the socially constructed situation, the authors interpret them in terms of the individual's natural intellectual ability.

Persistence of IQ

Much of The Bell Curve's emphasis is on the stability of IQ scores and the deterministic effect on educational, professional, and social success or failure. To a large extent, however, repetition enters in—the same type of tests are used at school, in college entrance exams, and in professional selection. It is little wonder that a successful test taker is rewarded each step of the way.

What is not discussed is that IQ score labeling becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. If from an early age the child is told that his or her intelligence should be low because his or her IQ scores are low, how can one expect the child and parents to actively work toward higher achievements?

One particularly damaging thesis is the claim that one's intellectual level does not change after the age of 10 (p. 130). It is exactly at this age that children, after mastering such basic skills as reading, writing, and arithmetic, start acquiring the higher-order conceptual reasoning necessary for successful study of sciences and humanities. These higher forms of reasoning do not appear spontaneously, but must be taught. If children are denied exposure to this conceptual reasoning because of their alleged low intelligence, they obviously will be at a disadvantage later in their schooling.

The claim that educational, mediational, and interventional programs cannot substantially change students' intellectual levels is a prime recipe for decline in education standards. Any attempt to urge teachers and students to raise standards will now be rejected on the grounds that they are unsuitable for average or low IQ students.

Dynamic Cognitive Assessment

We do not mean to suggest that we oppose any attempt to assess intellectual functioning. On the contrary, cognitive assessment can become an important source of information for educational and social intervention. To be useful, however, such assessment should conform to certain guidelines.

Evaluate rather than measure. Intelligence is not a “thing” to be measured, but a process to be evaluated. Thus assessment should take into consideration that intelligence is modifiable, complex, and multidimensional.

Attempt to reveal the propensity for cognitive change. Do not simply register the current level of performance.

Plan learning interaction based on mediated learning experience. Such a dynamic assessment, which generates samples of cognitive change, provides better insight into the student's cognitive potential than unaided performance registered by the static test.

Focus on the process rather than the product of cognitive change. Assess those cognitive processes and states that are responsible for performance and can be modified, rather than those that are rigid or inflexible. Note their relative significance and choose ways to modify them.

Aim to suggest the proper form of psychoeducational intervention. Do not classify or label.

The use of the Learning Potential Assessment Device with various groups of people has demonstrated the plasticity of human intelligence—far beyond that measured by IQ. For example, low IQ individuals were quite capable of learning and applying the principles of analogical reasoning that are embodied in the nonverbal tasks of the Raven Standard Progressive Matrices Test. This directly contradicted the claim of many IQ proponents—including Raven himself—that individuals classified as educable mentally retarded are incapable of mastering analogical reasoning (Raven 1965).

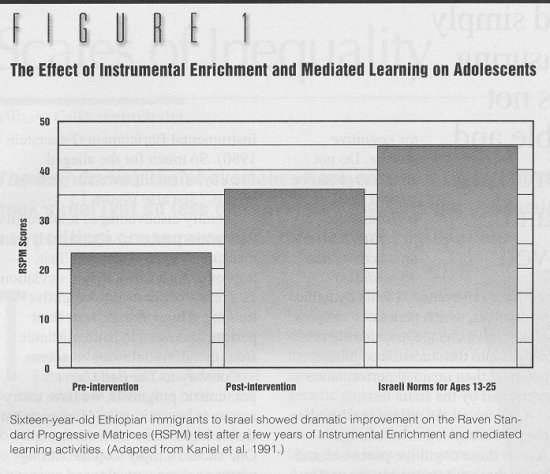

It was also shown that the performance of culturally different adults, who in preschool revealed a subnormal IQ (as measured by Raven Matrices and the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children), improved in a statistically significant way after exposure to the mediated learning experience and Instrumental Enrichment (Feuerstein 1980). So much for the alleged stability of intelligence test performance. (See also Figure 1.)

Figure 1. The Effect of Instrumental Enrichment and Mediated Learning on Adolescents

Sixteen-year-old Ethiopian immigrants to Israel showed drastic improvement on the Raven Standard Progressive Matrices (RSPM) test after a few years of Instrumental Enrichment and mediated learning activities. (Adapted from Kaniel et al. 1991.)

Socially disadvantaged adolescents, who performed at a subnormal level as measured by the Analogies Test, improved by a full standard deviation as a result of short-term cognitive training. Three months later their performance was indistinguishable from that of middle-class students.

Contrary to The Bell Curve's pessimistic prognosis, we have every reason to be optimistic. Human cognition is highly amenable to change. One should simply stop measuring what is not measurable, and start improving what can be improved.