Big ideas—powerful, generative educational principles and concepts—are receiving a great deal of attention in the new curriculum standards for almost every discipline. But what is not being addressed is how the growing number of diverse learners best learn the big ideas. On our way to world-class standards, how will we accommodate the 1 out of 10 students who receives special education service, the 2 out of 10 who live in poverty, the 1 out of 7 who lives in non-English speaking households (Barringer 1992)?

The instructional approach most commonly associated with world-class standards is inquiry, but while inquiry is a useful instructional approach, diverse learners often benefit from a wider array of approaches in meeting their instructional needs (Carnine and Kameenui 1992). One such alternative is the BIG Accommodation program for middle school students.

BIG accommodates a much broader range of diverse learners than is typically the case. Many of the mathematics and science videodisc courses used in BIG have been deemed exemplary by the U.S. Department of Education's Program Effectiveness Panel (PEP). Pogrow also cited the BIG mathematics courses for excellence (1993). Two of the more interesting findings from the studies included in the submission to the PEP panel were that 8th graders who had participated in the videodisc science course and supplemental problem-solving instruction scored as well on a test of problem solving in earth science as university science majors. In another study, remedial high school students scored as well as second-year AP chemistry students on a test of applications of core concepts in chemistry (Hofmeister 1992).

Seeing the BIG Picture

The BIG program is composed of three central elements— Big ideas from the content areas, Intensive instruction, and Great expectations. BIG stresses that while inquiry and child-directed learning are important, teachers can teach diverse learners more efficiently by emphasizing the application of knowledge.

Efficient learning is only one aspect of BIG, however. At the core of this program, teachers help students make connections among big ideas, use them in problem solving, and write about them. With intensive instruction around these applications, diverse learners construct knowledge and deepen their understanding.

How BIG Works

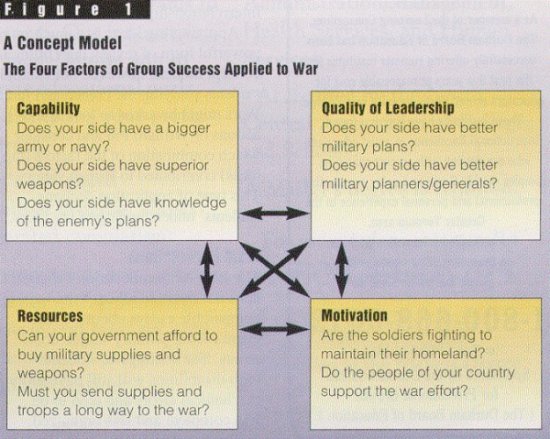

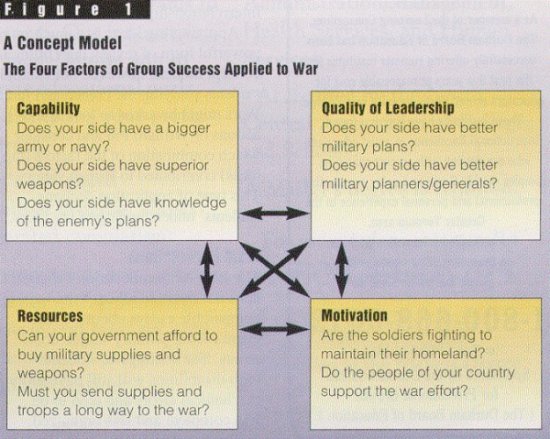

The best way to explain BIG is through examples. In history, students might be introduced to the “big idea” of leadership, for instance. By examining the characteristics of leadership, they can deepen their understanding of the qualifications, knowledge, and effectiveness of leaders like Jefferson, Washington, and Lincoln. But such study can be inadequate when the context is too narrow. General Robert E. Lee was a great leader, yet a losing general. So, students can go on to learn that the success or failure of a group depends on more than leadership: the motivation, capability, and resources available to a group are important factors as well.

These four “big ideas” might in turn be applied to situations in which a group is pitted against the elements (for example, the settlement of Jamestown); attempts to dominate other groups (the formation of parties in the United States); and struggles for human rights (the Civil Rights Movement).

From Direct Instruction to Concept Models

Intensive instruction around big ideas starts in science with videodisc lessons. In history it starts with a text written in a clear fashion with interspersed questions that help diverse learners attend to the big ideas and their component concepts. Big ideas are also graphically represented as concept models, the first being one that frames history as the study of how groups of people have succeeded and failed in solving problems. (See fig. 1 for an example of a concept model.)

Figure 1. A Concept Model: The Four Factors of Group Success Applied to War

Initially, teachers might ask students to fill in the words for a blank concept model. By using these decontextualized exercises, which they might repeat several times, teachers can impress on diverse learners a big idea's component concepts and their interrelationships.

Applying big ideas is a much more powerful form of review than filling in concept models, however. For example, students studying the French and Indian Wars might be asked to look at the actions of William Pitt and consider which combination of the factors (big ideas) contributed to British victory. This type of application deepens students' understanding of big ideas.

Great Expectations

The BIG Accommodation Program does not result in all students writing comparable essays about current events using primary source documents. The writings of students with disabilities will still have more mechanical errors and tend to be less complete and less organized.

The intent of BIG is not to make all students the same, but a key finding is that the writing of the students with disabilities in BIG programs is usually coherent, deals with causal relationships, and illustrates that students understand facts reasonably well (Kameenui and Carnine, in press). This level of performance on such a challenging task proves that the great expectations of BIG are not just a hollow slogan. In fact, great expectations with BIG are thoroughly justified.