Writing needs to be in the room—the classroom, that is—where disciplinary literacy happens. When students write, they have opportunities to articulate, revise, and strengthen their ideas, as well as to present and communicate their thinking. Writing is a critical skill in the workplace and has gained a more prominent role in disciplinary standards because of the Common Core. However, students struggle to meet proficient levels on standardized writing assessments (just 27 percent of 8th and 12th graders scored at or above proficient on the 2011 National Assessment of Educational Progress), and the writing that typically takes place in content-area classrooms is short, directed to the teacher, and asks students to simply reproduce knowledge.

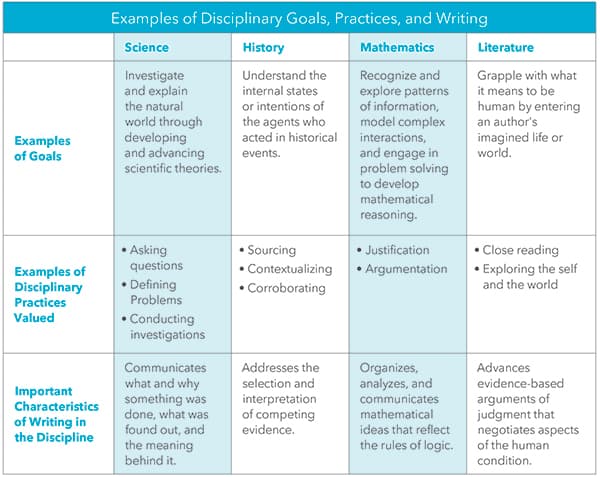

As writing teachers who have worked in elementary and middle schools, as well as in postsecondary teacher education, we recognize that teaching writing across the disciplines is no easy task. Writing can get "locked out" of the curriculum because it's time-consuming for students to produce and for teachers to assess. Additionally, because knowledge varies from subject to subject, so does what is valued as writing. Figure 1 shows some examples of how goals, practices, and characteristics of writing can shift across major disciplines. Sub-disciplines also vary widely (e.g., chemists value different types of practices and writing than biologists do), as do the purposes of writing within each discipline.

Figure 1. Writing and Disciplinary Differences

Figure

To address these challenges, we suggest three intentional and iterative practices to cultivate writing-rich curricular spaces: 1) writing beyond the teacher, 2) implementing sustained writing-feedback cycles, and 3) leveraging the tools and modes of technology to provide feedback and maintain a record of learning.

1. Writing Beyond Teachers

In the real world, writers have some control over their purpose and audience. For example, they write online fan fiction to share with other readers, op-eds for newspapers on issues they care about, or reports to share with colleagues. Effective writers understand how genre types, purposes, and audiences work together. Yet, most school writing is composed for the teacher, which often means that the authentic purpose gets subverted in the student's attempt to earn a good grade.

Meaningful writing tasks—the ones that stick with students—are grounded in their interests and extend beyond the teacher to include peers, families, the school, and online communities. For example, Rick challenges his 7th graders to engage deeply with the discipline of literature through spoken word poetry writing and performance, the culminating writing activity in a six-week poetry unit. Students incorporate multiple literary devices and other disciplinary practices into their pieces. They perform the poems at a poetry slam for an audience that includes peers, school faculty, parents, and community members. Students, although nervous, are excited by the prospect of being legitimized as poets. That being said, getting students to share their work broadly is a scaffolded process of building capacity and feelings of self-efficacy.

Students need opportunities to write about topics that draw on their prior knowledge and cultivate an investment in their learning. Writing tasks that invite students into disciplinary problem spaces can be powerful motivators to support learning. We have found that cross-disciplinary themes—such as patterns, change, structures, systems, and cause and effect—can be a productive place to start. For example, the concept of patterns is taken up differently across disciplines. Having students in a history class reflect on the statement, "Do you believe that those who do not learn from history are forced to repeat it?" will yield thinking significantly different from being asked, "What patterns exist in your everyday life and how do they help you make sense of your world?" in a mathematics classroom or "Why should we recognize universal patterns that exist in the natural world?" in a science classroom. However, all these prompts are generative, surfacing students' informal approximations (and misconceptions) toward disciplinary-learning goals.

Students need ongoing opportunities to engage in exploratory writing for audiences beyond the teacher. Apprenticing students into the practices of a discipline challenges them to think differently. Creating opportunities for students to grapple with content, negotiate meaning, and normalize their struggle is vitally important. Therefore, we recommend embedding regular, daily writing tasks that students share with peers. You can think of this as exploratory writing, or writing that is intended to establish a plan, investigate problems, raise questions, work out meaning, or engage in reflection. In essence, exploratory writing is writing to learn. Such writing helps students to figure out what they think (e.g., writing at the beginning of class to probe a topic or during class to elicit areas of understanding or confusion). Writing, like speaking, can mediate sensemaking and help students articulate their ideas.

With sufficient opportunities to explore their learning through writing, students can transition into more formal presentational writing tasks. This writing offers explanations, informs and entertains, reports and summarizes, and advances disciplinary arguments. Presentational writing showcases learning and provides an excellent opportunity to expand notions of audience; students can share their work across classes, with families, or online.

2. Sustained Writing-Feedback Cycles

Writing is as much about the journey as it is about the destination or product. In a 2017 interview describing his process as a writer (https://bit.ly/2JDwH2t), Ta Nehisi Coates shares an experience that resonates with many writers we know, including ourselves and our students. He says,

Everything I've ever written [has] started off…bad…. But I think if there's anything that makes you a writer, it is the ability to say, OK, that's bad … I'm gonna just put that away for a minute. And I'm gonna get up the next morning and … type over what I typed yesterday and maybe even type some more…. Then you get somewhere in the mediocre range. And if you're lucky, over a period of the next few days, you'll get somewhere that approximates good.

As writers, we know that writing requires regular time and effort—to work through and refine ideas, to meet the required guidelines, to play with language and structure, to wordsmith. And yet, in schools, we often expect students to produce quickly written presentational writing. They get one shot to showcase their understanding, often without opportunities to talk with others, receive feedback, or revise their ideas. If students are to see themselves as capable writers who produce high-quality products, then we as teachers need to cultivate instructional spaces that give students multiple opportunities to talk in preparation to write, as well as to write in preparation to talk. They need sustained blocks of time to write, during which they can receive feedback from peers (and teachers) and revise their thinking.

Students need to write and share their writing consistently and regularly. In our own classes, we build in time for students to serve as an audience for peers to share both exploratory and presentational writing. One way this can be accomplished, particularly with exploratory writing, is through writing groups. Peers can be apprenticed to move beyond surface-level mistakes and general praise to deliver more meaningful feedback. When students engage in iterative cycles of sharing their writing and feedback, they build communities of trust, which allows them to be seen in new ways by their peers, their teachers, and global audiences, ultimately empowering them to share their ideas in the world.

When students share, they need non-evaluative feedback. It is important that some writing feedback students receive is not graded or focused on grammar. Rather, non-evaluative feedback about their ideas and rhetorical choices will deepen their learning and ultimately improve their writing. For example, Rick structures "appreciative feedback" after each student performs his or her poem in the spoken word poetry unit. Classmates, teachers, and other audience members share their emotional reactions, personal connections, and lingering questions for the poet on a classroom blog. Sentence frames (e.g., This poem made me feel…, This reminds me of…) are used initially to help students deliver robust and meaningful commentary. One of Rick's students, Elle, stated, "A lot of people were really hesitant to share their [writing] with the class, including me. Then when I finally did, it really helped me. All the feedback was so encouraging and filled with good intentions. After that, it really made me happy and less afraid to share my [writing] with others." Non-evaluative feedback helps students move beyond such fears and gain confidence in their writing and ideas. However, this approach doesn't mean that writing can't also be evaluated at times, especially presentational writing that has been revised over time and represents students' best work and thinking.

Exploratory writing should lead to long-term writing projects. Although daily exploratory writing can be short and meaningful and involve regular feedback from peers (e.g., journals to document solution paths when solving multistep, open-ended math problems), the tasks should be a stepping stone in service of the unit's larger disciplinary goals. These smaller tasks can be viewed as drafts, increasing both the quantity and quality of writing in the content-area classroom. If organized well, these writing tasks can be trail markers toward formative assessment.

3. Leveraging Digital Spaces and Tools

One difficulty we have experienced in structuring long-term writing projects is keeping track of everything, including multiple drafts and reviewers' feedback. At the same time, we know that students love working with technology—particularly composing multimodally (e.g., with videos, podcasts, and images). We have both turned to digital platforms to help us monitor writing, and to digital tools to encourage our students to compose multimodally.

Digital platforms can help you manage and keep track of writing. We have found Google Docs useful for long-term writing or collaborative writing projects. Because Google Docs maintains a history of each version, the viewer can examine how a draft changes over time, including the feedback given. Becca regularly uses Google Docs to have her preservice teachers share, provide feedback on, and revise their lesson plans.

Rick's class also uses Blogger to showcase and share presentational writing for audiences that extend beyond the teacher. At the end of the poetry unit, writers post their poems to the blog. All audience members then share appreciative feedback through the comment function. Over the years, students have regularly expressed how much they value opportunities to receive feedback beyond the teacher. Jess said, "I really liked being able to receive feedback from others; it was nice to hear 30 opinions on my poem rather than one or two," while Meili stated, "As 7th graders, we spend a lot of time online and I like having a place that is always with you that shows the nice comments to something that you worked really hard on."

Digital tools can encourage students to write multimodally. We both harness digital tools to compose in various media, asking our students to consider how words, images, and sounds work together to create and shape meaning. Becca has her preservice teachers create video book reviews and give one another holistic feedback as audio or video files, in addition to giving specific written comments on a piece of writing. Her students also "re-mediate" their ideas across modes (e.g., creating and comparing arguments written as text only versus those recorded on video). In this way, the landscape of writing becomes more expansive to include composition beyond words.

Propping the Door Open to Writing

Carlos Fuentes, the famed Mexican novelist and essayist, wrote, "Writing is a struggle against silence." Writing functions as a pathway to communicate meaning and serves as a powerful tool to assert one's agency through naming one's world. As educators, we must open the door so that writing has a permanent invitation in classrooms where disciplinary literacy happens.