They appear in the form of coloring pages, crumpled or intricately folded notes of affection, and homemade jewelry. After a time, if you're lucky, they come as posts on social media, e-mails, an invitation to a quinceañera, or even a dedication in a master's thesis. Such tokens are evidence of a deeply felt, abiding connection with a student, the kind that can be lifelong, life-changing, and the fruit of all a teacher's labors.

How do we achieve such connections? How can we grow that level of relationship—the kind that fosters a learner through many academic hardships—with all our students, especially our most disenfranchised learners?

With some students, it's a cakewalk. They eat up our storytelling, our lessons, our attempts at bonding, and we're home free. Many other students, however, make us work for that glorious, nebulous quality of trust.

I'd like to share some effective ways to build trust with students, drawing on my 25 years teaching in schools that serve students from low socio-economic families. For 13 of those years, I've team taught with the same colleague. In that time, my partner and I have seen children in situations that would make even the most hardened veteran teacher cringe. Nevertheless, we've tried to nourish meaningful connections with each student, connections deep enough to weather the tough times that can erode such a bond. We want students to know that come attendance problems, behavioral issues, suspensions, and a myriad of obstacles, we will always remain on "Team Student."

Let Them Know You'll Be There

Beginning the first day in our 1st grade class, my co-teacher and I are clear with our message to each student: We love you. We believe in you. Your success in life is our goal and passion. From the first weeks, we strive to be approachable and look for every opportunity to forge a bond. We also strive to let students know we expect them to take control of and responsibility for their own learning. Too often students from poor families are on their own in terms of their education, with parents working or unable to help with school. Throughout each interaction with students, we tap into the belief that our job is to develop independent thinkers and problem solvers. We let students know that we'll help them succeed, but they must also do their part. This "No excuses, but wiggle room" approach has served us well.

It's important to be genuine and open with kids who have trust issues, as they often have multiple struggles in their lives. Acknowledge the elephant in the room. If a child has a problem in reading or math, he knows it. Talk about it, own the problem, and discuss goals and strategies to attack the issue head on. Even if that child doesn't contribute much to the conversation, your willingness to bring the fear and isolation out into the open goes a long way toward building trust.

Sharing experiences and offering support help affirm a child's reality, especially when you talk about things in a problem-solving way, not an "I-feel-so-sorry-for-your-terrible-life" way. Let your student know that you know times are hard—that dad's in jail or there's not enough food in the house sometimes. That young person will likely feel a palpable sense of relief.

We tell students often that once they are in our class, they are "ours" for life. We work hard with students and their families while they're with us, and when they leave, we try to keep track of them, asking to see report cards, keeping in touch with older youth through social media, and at times attending important events like graduations.

The students assigned to our classroom are truly our "learning family." A few habits help us keep track. We always keep last year's e-mail and street addresses for the previous year's students in our parent contact binders. While students are with us, we make notes in that binder about siblings (or cousins, aunts, or uncles) coming up to our grade. Because teaching kids in the same families year after year fosters our connection process, we give our administrators a list of upcoming "legacy" siblings and cousins to make sure they are placed in our class.

Although not every teacher may find this doable, we often appropriately contact parents of former students through e-mail or with a private social media message to check in on students. On a few occasions, when we feel it can be the difference-maker, we will give a family our cell phone numbers.

My co-teacher and I don't pretend we can do it all ourselves. We impress on students that they not only have us to rely upon, but they also have a whole school village of adults and peers who will help them along their learning path.

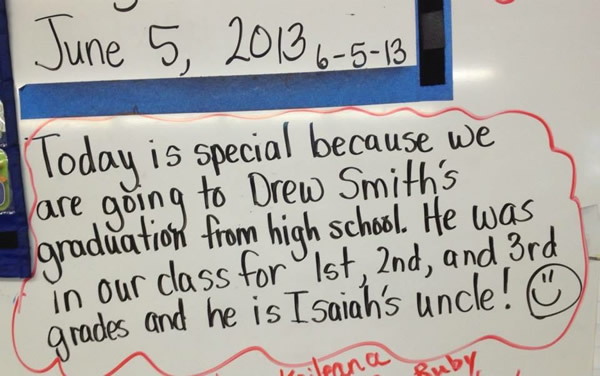

Two former students visit our class and talk about how to be a great student.

Photo courtesy of Theresa Crowley

Make a Plan Together

If a student has serious difficulties, create a workable plan of action together. Kids in trauma or those simply floundering with schoolwork need to feel that they're in control of their destiny. These co-written plans buoy students' confidence in themselves and in the school system.

Sometimes a student doesn't want to directly approach you, but you can start a conversation in writing. During writing time, I might write a note in a particular student's journal, something like, "Is there a way I can help you have a better day?" or "I see that you were sad after recess. Was there a problem I should know about?" Because we do this type of interactive writing regularly with all students, other kids don't catch on that I'm using the time to single out a particular student.

When you create a plan to help a student who has a life issue or behavior problems, write it with that student, so he or she has input into the process. Try these steps:

State the problem (When you get frustrated, you scream and disrupt others' learning).

Brainstorm possible solutions. Honor students' ideas, far-fetched as they might be. Discuss the feasibility of different solutions and agree on one or two to try.

Write a plan for what everyone involved will do. (Dylan will try deep breathing if he has to wait for his teacher's help, and Ms. Crowley will let Dylan know when she's available.) We make a big deal out of everyone involved signing this negotiated agreement. Even the lunch lady may be brought in! Post the plan in an agreed-upon place.

Make Each Student an Expert

Making a student "the expert" helps build confidence and raises that student's status within the class. We want students to know the areas in which they excel, as well as those in which they need to put more effort. Even the most struggling student is good at something. A student who battles with number sense yet does wonders in geometry becomes our "expert at the tangram station," for example, who thrives on helping other students.

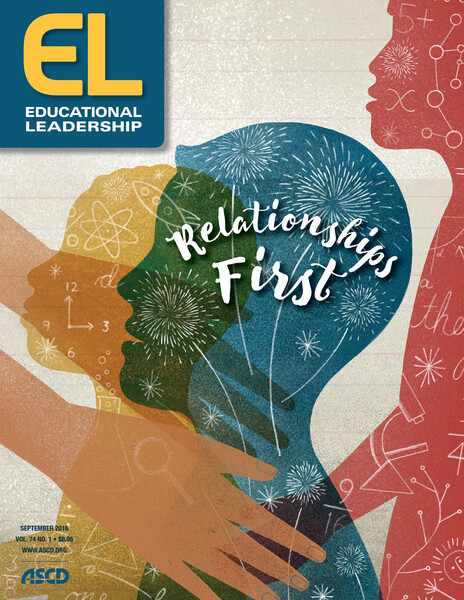

When you highlight students' strengths, mention your expectations for excellence. Repeatedly. Our students know we expect them to graduate from high school (and that we'll attend their graduations). They know we expect them to go to college or trade school or pursue another ambitious goal.

Message to our current class about the graduation of a former student.

Photo courtesy of Theresa Crowley

Find a Way to Get Them to School

Attendance problems are the enemy of trust. Students who aren't in school are disconnected from education, as are their families. We tell students that we expect them to come to school every day, unless they're truly sick (with fever or throwing up) or someone in the family has died. Our school keeps a stash of alarm clocks to give students when necessary. Our counselor has a routine with several students; they check in with her each morning (and maybe each afternoon) to sign a daily chart for attendance and receive a sticker for each day they're present. At times, we've even had an administrative team (an administrator and a counselor, nurse, or available teacher) who would go to a student's house with a thermometer. No fever? No worries, we'll take you to school. Their daily attendance sweep improved several chronic absentee situations.

One year, we noticed that all the students in one family tended to be absent on the same day. Teachers who had these siblings worked together to track their absences. Each time the students were absent, I called to speak to the father in Spanish, and the administrators inevitably went to pick up the kids. Slowly, attendance for all five improved.

We discovered a family who had moved seven times within two years, a sure killer to academic progress and connection to school. When the family moved again mid-year, I offered to pick up the students each morning, as their house was near my daughter's middle school. Some may call this level of help enabling the parents. I viewed it as an opportunity to forge a connection with a family in need.

Our hardest case was a pair of brothers who were dragged to school daily, kicking and screaming (literally), by police officers and administrators. The first 30 minutes of the day involved some harrowing moments. After the screaming wound down, teachers alternately ignored these boys' provocations and tried to entice them into participating.

Over time, we realized that the older brother, who had a severe learning disability, was artistic. I invented the special privilege of using my camera to take photos of classroom activities, telling him, with word and deed, that I trusted he could handle it. I printed those photos and he wrote about them, then made them into books that he read to everyone he met.

Use the Village(s)

Instituting class meetings to solve problems or generate ideas goes a long way to helping students feel a sense of belonging and kinship. We hold class meetings frequently to address concerns, model communication and problem-solving skills, and foster trust among students.

It's worth guiding these meetings in such a way that you can address problems you know particular students are having without making those students speak. Some teachers have boxes in which kids can anonymously deposit problems or topics they want to bring to the class meeting. We often ask specific kids to help us talk about problems—students who are great at role-playing, who have issues similar to those we know another student is facing, or who are popular (so their words pack a punch). We may even bring in older or younger buddies from other classes. School counselors can be a great resource for designing and conducting class meetings.

The more people students trust, the more accepted and ultimately successful they will be. Building trust isn't just the role of the classroom teacher: All school personnel should be involved. Does a student like sports? Hook him up with the teacher who's a football fanatic. Does she like a certain musician or style of music? Introduce her to the teacher down the hall who just went to a three-day concert. Our school once instituted a teacher buddy system, in which someone other than a student's classroom teacher was charged with making an extra effort to check in on each kid. Each teacher buddy simply needed to devote a highly focused 15 minutes a few times a week to making direct contact with their student. After a connection had been made, some kids began to approach their "other adult" with good news or problems.

Go One-on-One

Look for times you can arrange some one-on-one time with students who seem trickier to bond with. Invite a particular student or a small group to have lunch with you. Or, once a week, turn your prep time into an informal schmooze time. Invite kids you hope to build a relationship with to drop in when they're available and talk about topics that would interest them.

You might spontaneously connect with a student who's at loose ends before or after school. If I see a student wandering the playground a bit too early in the morning, for instance, I sometimes invite her (or him) into my classroom for a few minutes. The student takes my chairs down or sorts books, we chat for a few minutes, and then I send her on her way.

Likewise, never underestimate the power of a home visit or attending a student's soccer game. Going out of your way to see a student or his family outside of the school day makes a big impact.

Use Humor

Laughter and an appreciation for the ridiculous have helped my co-teacher and I endure our long (and, at times, brutal) careers as teachers. When report cards are due, your printer runs out of ink, and the school network is down, what else is there to do but pause, take a breather, and laugh? We might call this "recess for your mind." Accepting the inevitability of a ridiculous set of circumstances, laughing about it, and moving on with life is something we all need to get better at. And when we laugh with students, we strengthen bonds.

Take joy in singing silly songs together. Bond by sampling an exotic (but curriculum-connected) food. Try out the latest dances together (you should see my 1st graders dance the Whip and Nae Nae). Any dance can be learned through a YouTube clip. (Just preview the dance first to be sure it's appropriate.)

Crucial Connections

My co-teacher and I are in touch with many former students. Some reach out to us to share a memory or make a connection when we least expect it.

Last year, one of my 1st graders came down with pneumonia and was taken to the emergency room. It didn't surprise me to hear later that as soon as the doctor entered her room, this child told him that he needed to hurry up and help her get better, because she had to "get back to her learning family." That's the kind of connection I hope to have with every student.

Tools to Build Trust and Connections with Students

Give a student a special job or privilege that you know he or she can handle.

Make an appearance at students' extracurricular activities.

Connect outside of school. Make a home visit or meet with a student's family in a local coffee shop. Occasionally, drive to a student's home to retrieve forgotten homework or library books.

Cultivate former students and parents. Invite them to come to your classroom and talk about how they overcame obstacles. Go to former students' graduations, take pictures, and share them with your current students.

Go out for recess when you don't have recess duty and chat with—or play a game with—your students.

Take on a before- or after-school duty to connect with former students.

Go out of your way to adopt ideas and suggestions that students make. Refer to the student who had the idea by name ("Joe suggested this math game").

Use social media to keep in touch—appropriately and as suitable to your circumstances—with current or former students.