How a rock-throwing student taught us to challenge our assumptions.

In the late 1990s, I (Gillian Crane) was a young, new teacher at The Masters School, a boarding school just outside New York City. I had an office that overlooked the athletic fields, and around this building was a section of large, smooth pebbles that separated a path and grassy area where fans would sit and cheer on their friends. Most mornings I would enjoy this view, watching as students headed to class, chatting and laughing.

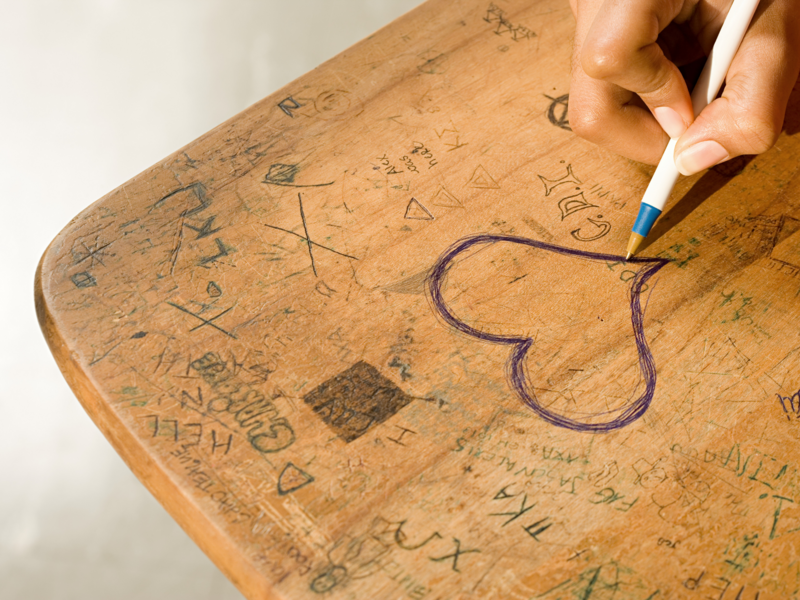

One morning, I saw a 9th grade student pick up a handful of those large pebbles and head to the chain-link fence on the side of the field. He sat down on wooden bleachers and began to throw the pebbles, one at a time, onto the field, quite forcefully.

My first instinct was to open the office window and yell at him to stop, to lecture him about how throwing rocks onto the field could damage the school’s lawnmowers and is disrespectful to the maintenance staff. But I stopped myself, left my office, and went down to the field to talk to the young man chucking rocks.

Instead of yelling at him, I asked him how he was doing and what was going on. I learned that he had just broken up with his girlfriend and that he was feeling terribly homesick from being so many miles away from his family. After we talked, he acknowledged that he felt better. I was then able to explain how the rocks on the field could damage the equipment used to cut the grass and affect the work of the maintenance staff. He ran to pick up the rocks and went off to class with an expression of relief on his face.

The rock incident stayed with me throughout my professional career as an educator. It made me reflect on the different approaches to discipline: from a superficial one aimed at changing behavior (telling the student to stop throwing pebbles), to a compassionate one aimed at understanding the forces that are propelling the pebbles.

Many years after the pebble incident, I became the dean of students at The John Cooper School in The Woodlands, Texas, where discipline is an integral part of my job. I was able to hire my former colleague and coauthor of this article, Diego, as a counselor.

At The John Cooper School, the two of us have spent the past five years working to incorporate the “philosophy of the rocks” into our approach to discipline and counseling. We believe that more schools could benefit from the lessons we have learned over the past two decades working with thousands of students.

Here are some of those lessons:

It isn’t about the rocks. It’s about the forces that propel them. Problematic behavior is a manifestation of something deeper. A pebble being thrown is an expression of a psychological need that is not being met. If discipline stops the pebbles but doesn’t address what is propelling them, it will not serve the student.

The soul of education is connection. The pandemic has made this more obvious than ever before. Discipline is just another way in which we connect. Because of the intense emotional component of discipline, we need to reflect on the philosophy behind the type of connections we want to create. As educators, we have a power imbalance in our favor. We decide how we use our power to promote empowerment, how we use external control to promote self-control. Meaningful discipline is based on modeling kindness and compassion.

Identifying and addressing the needs behind the behavior takes time and effort. Educators are already stretched thin. Compassionate discipline requires a systemic approach that allows educators the time not only to reflect on the true purpose of education beyond curriculum and behavior management, but also to act on it.

A good illustration of this point comes from a famous Princeton study that uses the parable of the Good Samaritan, a biblical story about helping people in need that we may encounter in our daily lives. The researchers wanted to examine the effect that time pressures had on students who had the opportunity to help others in need. The study’s subjects were instructed to walk to a different building in order to give a brief talk to an audience on either the parable of the Good Samaritan or on a “non-helping” topic. The researchers had designed the study so that on their way to the talk’s location, the students would encounter someone in need of assistance. It was a clear opportunity for those who’d read the parable of the Good Samaritan to put into practice what they were about to preach, but only 10 percent of those students stopped to help the person in need. Another group that had no time pressure stopped to help at a higher rate.

As the study concluded, the content of the sermon was not the key to helping—having the time to help was. The same applies to schools’ approach to compassionate discipline: good intentions fade away when there is not enough time for them. If we believe in compassionate discipline and want to implement it as a systemic approach, we need to carve out dedicated time for that endeavor. A shoehorned or rushed initiative will not reap the benefits to our communities that we seek.

“Getting in trouble” might be the only chance for some children to get the guidance and the support they need. Disciplinary problems can be exceptional opportunities to have a positive impact on students' lives. Keeping this in mind can transform the way we approach challenging behavior. Problems become opportunities. The problematic behavior of throwing the rocks can be seen as an invitation to connect, to explore unmet needs, and to offer guidance and support.

We need programs that provide tools and practices for all members of school communities, not only children. Generation Z is growing up in a world that is significantly different than the one their teachers and parents grew up in. If we want to be able to understand their world, their needs, and behavior, we need systemic approaches to social and emotional learning that are designed to train the adults in the community as well as the children. Problematic behaviors need to be understood in the context of the social and emotional development of children and adolescents, and they need to be addressed by adults who have the knowledge and tools to be models of self-regulation and compassion.

Our school chose the RULER approach, developed at the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence, for these reasons. RULER is an acronym that refers to five emotional intelligence skills: Recognizing emotions in oneself and others, understanding their causes and consequences, labeling them, expressing them appropriately, and regulating them. When students and adults have this common language and are familiar with these skills, conversations about emotions become much easier and productive.

A compassionate approach

Finally, we’d like to share our approach when talking to a student who has displayed problematic behavior:

Connect with the emotional experience of the student and validate it. Any student who is “in trouble” is having an unpleasant experience. Let the student know that you are willing to understand their experience and what led to their problematic behavior. Listen mindfully, without judgment. A simple strategy you can use is to validate the student’s feelings by using the expression, “It sounds like you are feeling….”

Try to identify the psychological need that is being expressed through the problematic behavior. Academic dishonesty might be a desperate attempt to be loved by parents with unrealistic expectations. Disrespectful behavior might be an attempt to gain peer recognition or to have an adult set limits in a respectful way. Throwing rocks, like the student in the opening story, might simply be a way to express emotion.

Help the student reflect on the causes of the behavior first, and then on the consequences. Help them see how their emotions, their thinking, and their actions are interconnected. Guide them in becoming scientists of their own experience. There is no judgment, simply curious observation. You are not trying to get them to say they are wrong or guilty. You are trying to help them develop the self-awareness that will make self-management possible.

If disciplinary consequences are granted, make sure they connect with the reflection process outlined above. At our school, we have developed different modules that students must complete as part of the disciplinary process. If the problematic behavior has been mistreating others, they might have to complete a module on kindness and compassion. The idea behind it is not to use kindness and compassion as a punishment (what could be more ironic!) but to give an opportunity to reflect on emotions, thinking, and behavior.

In the end, when we focus on the rocks instead of the forces behind the rocks, we miss an opportunity to reach students and make a connection. It can take years for those connections to pay dividends, but real learning—deep and lasting learning—only happens when there is human connection, empathy, and compassion. It’s not about the rocks; it’s about the person behind them.