"I, Thou, and It – a three-way relationship in which "I and Thou" are the people (often a teacher and child, though not always) and "It" is the content that compels both." —David Hawkins, The Informed Vision, 2003

Complexity and uncertainty are here to stay. In the midst of a pandemic, global climate disruptions and raging wildfires, an upcoming presidential election, and significant social unrest as protests continue for racial justice, we recognize the importance of diving beneath the surface of our classroom content. In our current climate, fact can blur with fiction, science can blur with wishes, and journalism can blur with persuasive arguments. Deeper learning insists that we develop the critical and creative skills that help us to search for what is true, listen to one another with understanding and empathy, and unpack problems when confronted by complex and ambiguous situations.

Exposure to challenging content by itself does not ensure deeper learning. Deeper learning requires a psychologically safe environment that is open to diverse perspectives and respectful of interdependent thinking. We need classroom environments that help students to manage the cognitive dissonance stemming from content that challenges their assumptions and beliefs.

Based on the work that we have been doing with teachers over many years, we have learned that meaningful relationships grounded in deeper learning use three components: 1) a trusting learning environment; 2) assessment interactions that enable students to attend to themselves as unique learners; and 3) content integrity.

1. Develop trust so the learner feels a sense of safety and credibility

Trusting relationships among all people in the learning community are key to developing psychological safety. These relationships include structured processes for students to exercise voice and choice individually and when working with others. Trust and agency develop gradually through practice and with opportunities for student self-discovery and inquiry around worthy content.

Design a whole-class survey to know the students and help them know each other.

A positive class culture is one in which students know themselves as well as others better. When students have access to the results of the survey, they can think intentionally about what supports them and their peers as learners, what they want to read or learn, how they want to structure their studying, and how they can process and demonstrate their learning. They can build connections between their lives, academic interests, and aspirations for their future. Ultimately, this leads teachers to group and regroup students based on different responses.

Some academically oriented questions might be:

What are you looking forward to learning this year? What is the easiest part about school for you? What is the hardest part? What are some of your preferred choices for how, where, and when you like to study? When you are having a tough time, what do you usually do? When you envision leaving this class at the end of the year, what are 3-4 goals you hope to achieve?

Some personally oriented questions might be:

- What name do you want people to call you?

- Who would you like me to call when I have good news about you to share?

- What are you good at outside of school? What are some of your interests?

- What would you like your friends to say about you?

- What would you like me to know about you?

- If you could study anything of your choice, what do you want to know more about?

Introduce yourself in ways that invite students to share who they are.

Amanda Christian, a high school geometry teacher we interviewed at Humble ISD in Texas, said she used flip grid to introduce herself and model how she wanted her students to introduce themselves. She talked about some of her experience during the isolation at home: her fears, her discoveries, what she found time to do that she had not done. She described what she loves about geometry and why she wanted to teach the subject; Finally, she talked about some of her expectations for the year. She then asked each student in her class to introduce themselves to her and to one another. This set the stage for a learning environment that promised to be thoughtful, sensitive, personal, and academically challenging.

2. Ensure that students own assessment for the purpose of learning

Tap into what they already know.

Because every student arrives at a learning experience with a unique array of background knowledge, understandings, biases, and attitudes, students can benefit from diagnostic or baseline assessments that help them uncover what they know and can do. These diagnostics can be as simple as one or two questions, short quizzes, problems that resemble the problems students are expected to solve, or graphic organizers that ask students to identify what they know and what they want know about a subject. Students can use their own diagnostic data to recognize what they know, set goals, and begin to document their learning journey.

Teach students to self-monitor and adjust.

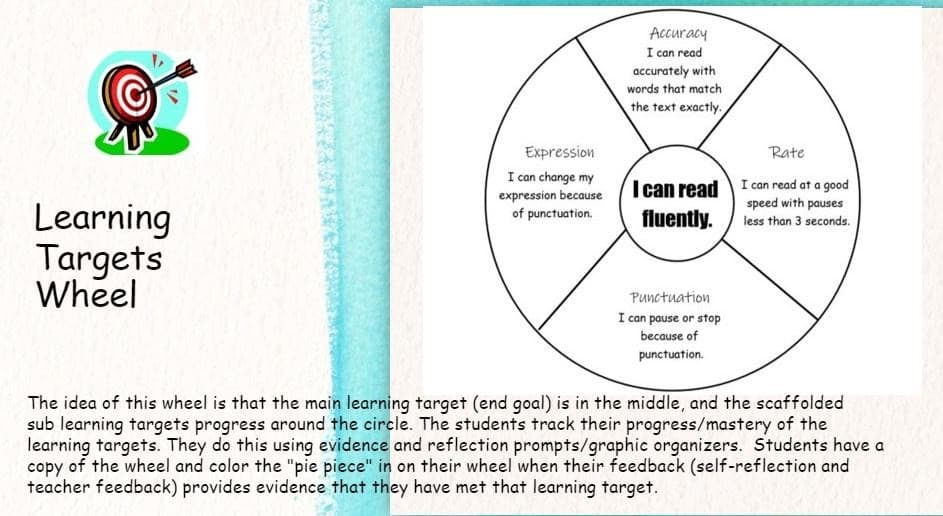

Formative assessment is a practice that is especially impactful when students are at the helm and can assess their understanding and skill attainment to determine their progress and what they need to improve. Molly Fuller, a 2nd grade teacher in Penfield Public Schools in New York, uses a learning targets wheel for her students to target their rate, accuracy, punctuation, and expression of their sentence fluency. In this wheel, the main target (goal) is in the middle and the subgoals—rate, accuracy, punctuation, and expression—are in the middle. Students have a copy of the wheel and color the pie piece on their wheel when they can provide evidence that they have met the learning target.

Use assessments that promote self-understanding and student choice.

Offering options for how to demonstrate learning promotes agency. When those choices include deciding on a problem to investigate or an author to study, students become more invested in their learning (Martin-Kniep &Picone-Zocchia, 2009). Stephen Johnson, a 9th grade science teacher in West Irondequoit School District in New York, encourages students to use mind maps to make sense of what they are learning. As a culminating assessment, students produce a map to illustrate their understanding and make connections to previously learned concepts. The mind maps look as different as each student’s thinking might be.

Use explicit criteria to promote self-assessment and improvement.

Teachers can increase student agency and success when they ensure that students understand what is expected from them and have the information they need to monitor and improve their progress. Strategies for doing this include inviting students to assess their own and each other’s work against criteria they have co-developed, asking students to translate the standards into their works, and helping them annotate and sort work against different levels of quality.

Scott Wright, a 6th grade teacher in North Syracuse Central School District, developed a self-assessment checklist for the literacy standards. He asks the students to use each standard as a goal statement and score themselves on how well they are doing. He includes the Habits of Mind as an integral piece of the responses.

For example, the standard might be: Find and use text evidence to support (write/talk/think) analysis of what the text says directly as well as inferences (“So What,” “Now What”) you can make from the text. Students can score and show evidence for these “I can” statements:

- I can collect data and then reflect on my thinking.

- I can think and communicate with clarity and precision by using …

3. Maintain content integrity.

Content integrity begins with teachers assuming that they have some agency and responsibility over the decisions about what students should learn. That agency is evident when they ask themselves to reflect on what they believe are the most important outcomes that students should attain and use that reflection to carefully review the content and other standards they will include in their curriculum design. While knowledge continues to accrue every day, some knowledge, skills, and dispositions are more essential than others.

Content integrity is dependent on:

- Establishing clear and specific purposes for learning

- Stimulating student curiosity and wondering about larger issues and questions that will matter to the students

- Engaging students in addressing real world problems

- Explicitly teaching students processes to meet the challenges of life beyond school.

Although teachers may have a required set of standards and curriculum, they need to focus on larger outcomes that will prepare students with the essential skills for problem-solving, innovating, and designing possibilities that address future challenges (McTighe, 2019). The clarity that stems from a commitment to such outcomes promotes students’ capacity to take a critical and discerning stance when confronted with complex issues that require distinguishing fact from opinion or separating emotional wishes from science.

References

Costa, A. & Kallick, B. (2008). Learning and leading with habits of mind. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Martin-Kniep, G. O., & Picone-Zocchia, J. (2009). Changing the way you teach, improving the way students learn. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

McTighe, J. &Curtis, G. (2019). Leading modern learning, 2nd. ed. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree.