Schools face continuous and increasing pressure to improve. As a former principal, I experienced frustration when initiatives that I believed could benefit our students failed to gain traction, from improving students' lunch experience to eliminating A–F grading that perpetuated fixed mindsets. Many education leaders I know would agree that most change initiatives either fail to "stick" or never scale.

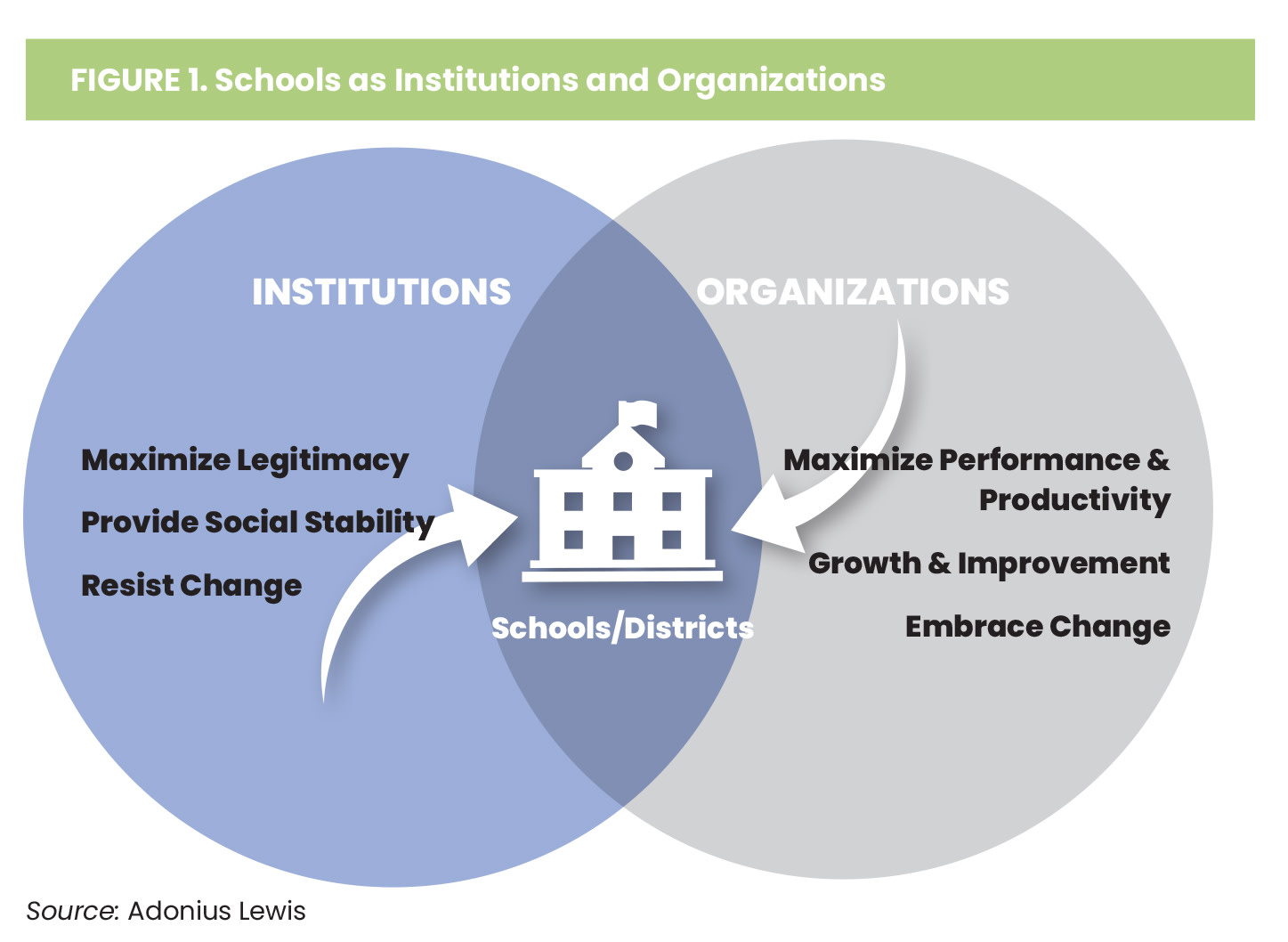

Why does this happen? Because many of our change efforts frame schools and districts as organizations. In a vacuum, organizations aim to maximize productivity. However, schools and districts are also institutions. Institutions, such as banking, government, law, and education systems, provide stability and meaning to our society. Instead of productivity, institutions strive to maximize legitimacy, which is the perception of what is socially accepted and appropriate, and how it comes to be. As social entities that societies rely on over generations, institutions tend to be rigid and resist change much more than organizations. Existing at this intersection makes school systems unique (see fig. 1).

I came across Institutional Theory—a fancy way of explaining why institutions work the way they do—as a Harvard doctoral student in educational leadership. One of my residency projects involved leading a change initiative across a large school district during the pandemic. By combining my understanding of school systems as both institutions and organizations, I was able to make significant progress in establishing conditions for change. I learned some key lessons in change management in the process.

A Paradox of Change

As organizations that are also institutions, schools and districts represent an interesting paradox: They're part of a system designed for social stability (i.e., to resist change), yet face increasing pressure to improve continuously (i.e., to embrace change).

Within this dichotomy, many educators who want to embrace change often fall, unintentionally, into the habit of reproducing old, counterproductive mindsets and structures that hold a lot of legitimacy. In other words, educators (and entire school systems) fall into the "that's the way it's always been done" trap.

I am not exempt. Over the years, I employed "sage on the stage" pedagogical approaches as a teacher. I used top-down change tactics as a leader at the expense of building important relational buy-in. Institutions, and the educators and leaders who are a part of them, tend to elevate and promote ideas, people, and behaviors that hold legitimacy—and reject those that don't. For that reason, new and different ways of thinking tend to be resisted and then fizzle, which stifles learning and change.

So, how can ambitious leaders leverage legitimacy to create the shifts in thinking and doing that they want to see? First, we must understand legitimacy. Legitimacy can function like a social currency within institutions, creating pressure to conform to the status quo. For example, the staff in a school may know that their school leader tends to respond negatively to constructive feedback. So, the assistant principal withholds great ideas that could potentially improve schoolwide performance because she needs good performance reviews from the principal to eventually become a school leader in the district. These lost opportunities to improve contribute to stagnant student performance over time.

Leaders must strategically legitimize shifts that increase individual, team, and system-level learning in alignment with organizational goals.

Examples like this illustrate how, without legitimacy or social currency within institutions, brilliant ideas tend to "die on the desk," talented employees can get overlooked, and change initiatives often fail. But legitimacy also gives a person the power to convene others, advance work, set norms, and make and enforce rules or policies. Thus, change-oriented leaders must strategically legitimize shifts in ways of doing and thinking that increase individual, team, and system-level learning in alignment with organizational goals.

To do so, we must turn to the forces that influence legitimacy—and use them to our advantage.

Influencing, Teaching, Leading

According to Institutional Theory, there are three forces that influence legitimacy. The first is our schema, also called mental models. These are deeply held assumptions that we use to make sense of the world around us. Any sustainable change must be supported by a shift in the meaning-making system of the individuals involved in the change. This requires communicating a deep "why" along with a clear "what" and "how." Failure to account for shifting mental models unfairly asks individuals to meet new expectations using old ways of thinking.

The second force that legitimizes change initiatives is normative, or social, pressure. What we consider "normal" is influenced by our social networks and peers. Relationships are key to this force, specifically working in teams and targeting influential individuals, which can accelerate how quickly and deeply shifts become normalized. The absence of healthy social pressure makes it more difficult to hold ourselves to commitments we've made to think and act differently.

Finally, sustainable change must be supported by policy, or the regulatory force. Without being supported by policy (or those who approve, create, and enforce policies), change efforts can be quickly thwarted by supervisors or boards. Understanding what these policymakers care about protecting allows you as a change leader to know the boundaries of any effort you initiate.

Ultimately, then, improving the performance of a school and district boils down to disrupting influential stakeholders' less productive ways of doing and thinking—which are largely predicated on (often unchecked) assumptions and social norms operating within the boundaries of policy—and legitimizing new ways of doing and thinking. However, legitimizing this disruption first requires stakeholders to see how their current ways of doing and thinking contribute to current results. Reflecting on change projects I have led at the principal and district level, I offer the following considerations to help leaders maximize legitimacy for change initiatives.

1. Gather interpretations of the "problem" from diverse perspectives. Reflect them back to stakeholders.

Interview stakeholders who are closest to the problem you are trying to solve to gain a nuanced understanding. Hearing multiple perspectives and honoring the history that informs the present helps ensure that the work you decide to take up is perceived as a value-add. People need to perceive the change as a value-add to commit to it.

Share your understanding with a small, trusted group along the way. After your data-gathering process, reflect the problem back to the stakeholders you are working with to ensure you are framing it accurately and digestibly. This step begins the important work of aligning stakeholders' mental models to see the "problem" similarly, which grants legitimacy to an emerging perspective. The depth of a group's conviction to support a change will not exceed their belief in the quality of the analysis. And their belief in the quality of the analysis will grow if they see and hear the voices of their member groups reflected. As a principal, my initiatives with the least success were usually the product of an analysis that excluded my team.

2. Build relationships and social capital with those who can advance or derail your efforts.

One common misstep I've observed is for leaders to place distance between themselves and those who might oppose their efforts. This usually leads to increased resistance because these people will likely experience the change as a loss and something being done to them, instead of with them. Driving sustainable change requires showing a genuine interest in resisters as contributors. Doing so allows us to understand their values, hopes, and perceived threats, which are typically at the root of resistance.

During my residency, I spent the first couple of months building rapport with the superintendent's cabinet members and central office administrators through coffee chats and offering to fill gaps where extra capacity was needed. The initiative I hoped to lead would eventually require the approval of the chief academic officer, who held deep personal and professional relationships with countless influential stakeholders. My project touched on her area of work because it involved academic strategy, so could be perceived as threatening to her. So, I knew I needed to make her a partner in the work. Throughout my project, I continuously called in the opinions of her and her team members while also validating their previous efforts. Our partnership legitimized the project to broader stakeholders because her team possessed significant normative and regulative legitimacy within the district.

3. Construct a "core change team" and designate a recurring team learning space.

At the school level, the core change team could include leadership team members, influential teachers, and a parent or community-based stakeholder, depending on the initiative.

This team should:

- Represent diverse positions and perspectives within the organization, including those who seek change and those who might resist it.

- Include members that possess regulatory and normative legitimacy.

- Regularly convene in a team learning space.

The district project I led aimed to improve the learning conditions of the superintendent's cabinet and lead it to collaboratively develop an academic improvement strategy with schools. My core change team included that 17-member cabinet as well as 9 principals and their school-based leadership teams. This group varied in tenure, interests, experience with instruction, and status.

A team learning space allows for ongoing individual and collaborative processing of various data collected in relation to a team's shared goals. Team learning spaces are critical because they can combine all three institutional forces. Therefore, the learning that occurs in these spaces over time becomes the fuel for individuals and teams to recognize the connection between their thinking, their actions, and the current state.

Our team learning space consisted of scheduled site visits to schools. If possible, you can repurpose an existing structure (a designated space and time to convene), such as staff meetings, PLCs, recurring cabinet meetings, or leadership team meetings.

4. Develop team skills in evaluating evidence (separating fact from inference).

Implicit mental models (assumptions) cause us to unintentionally jump from fact to inference, which protects the status quo. Slowing down our thinking to separate fact from inference is integral to learning and breaking out of old cycles.

Though this skill is simple, it must be practiced. To accomplish this, I held workshops on how to take low-inference observational notes. We practiced by observing videos of classroom teaching and only writing down what we could see, hear, or count in relation to the students, teacher, and content. I pushed the group to be rigorous in evaluating evidence, asking them to respond, "What's the evidence of that?" to colleagues' claims when an inference was misstated as a fact. Over time, we normalized this practice in our learning space.

5. Designate a team learning protocol.

The team learning space places decision makers, implementers, and those impacted together to review and identify trends and patterns in the current data and make meaning of those trends. The team must explore root causes that make clear their thinking on how their actions contribute to current outcomes. At the school or district level, this typically involves cycles of reviewing student achievement data and conducting co-observations of whatever area you're targeting, then holding debriefing cycles with your core change team. Effective protocols should center the evidence, foster rich discourse, and introduce healthy norms that make the space feel safe.

My residency district work consisted of adapting and co-constructing a practice of instructional rounds with my core change team. We observed many hours of classroom instruction in small groups across many schools, partnering with each school's leadership team. In each school, we spent the afternoon debriefing our observations from the morning.

Some principals already adapt aspects of this practice with their leadership teams. Remember, the process is about creating conditions to shift influential stakeholders' mental models and actions while leveraging the social pressure of teams to further legitimize those shifts. Well-executed instructional rounds can accomplish this in several ways. First, the practice of separating evidence from inference helps stakeholders uncover specious assumptions that perpetuate the status quo. Second, repeated engagement in the team learning space disrupts and replaces previous rituals and routines while normalizing the rigorous examination of goal-aligned evidence. And finally, the likelihood of teachers acting on their new learning increases because people are more likely to keep commitments that they make in the presence of others.

6. Create real-time opportunities to improve knowledge and practice.

Most of a person's development occurs on the job because that is when we form the habits connected to important tasks. Because of this, real-time coaching can be powerful. It can guide individuals and lead to improvements immediately, which builds better habits. Given the time pressures on educators, it is not possible for everyone to be coached in real time. But change leaders can provide "fingertip accessible" resources that communicate the technical "what" and "how" of the desired shifts so that leaders, teachers, and other personnel are not left to rely on old patterns of thought and behavior to execute new expectations.

Resources might include quick reference guides, rubrics, flow charts, diagrams, PowerPoints, or checklists. Key shifts in thinking and behaviors should be broken down into bite-sized, "sticky" language with visual aids (imagine directions for assembling furniture or a one-pager for how to wash your hands). As a principal and in my district work, I've learned to create documents that can be easily integrated into people's personal planners or organizational systems. Though we live in a digital world, using physical resources helps to build habits and can also represent a symbolic reminder of the desired change.

Schools and districts, which are institutionalized organizations, require leaders to create legitimacy for change initiatives before and throughout the change process, using mental models, social norms, and policy.

Breaking Old Habits

A solely organizational-change perspective is insufficient for leading change in schools and districts. Schools and districts, which are institutionalized organizations, require leaders to create legitimacy for change initiatives before and throughout the change process, using mental models, social norms, and policy. Without these three levers, the system will revert to the status quo.

Disruption of influential stakeholders' unchecked assumptions and perceived social obligations precedes all sustained change. This disruption requires change leaders to create team learning environments that allow key stakeholders to establish a common perspective on the problem to be solved. Leaders then must build systems to support continuous capacity building to enable shifts in ways of doing and thinking within everyone who's integral to the change.

Though the road may be arduous, a more accurately mapped terrain that accounts for institutional forces through policy, stakeholder buy-in, and continued adult learning and growth can support us all on our journey toward sustainable school- and districtwide improvement.