Sixteen years ago, I began teaching at Harvard University after a 30-year career as a special education teacher and administrator. Although I was teaching courses on inclusive education, I was surprised by the number of students with disabilities in my classes, sometimes approaching 20 percent. I had been a doctoral student at the school a decade before and could only recall one student with a disability attending Harvard at that time.

I was pleased with this change, of course, since improving educational opportunity was the focus of my career. Obviously, the work of educators and families in this regard was bearing fruit. Indeed, one of the most significant accomplishments of the U.S. education system has been the increasing numbers of students with disabilities attending higher education.

I became intrigued by these students' stories. How did a young person get to Harvard if he couldn't hear, or if she had difficulty speaking because of cerebral palsy, or if he started reading later than other kids? I began asking some of these students, "How did you get here?"—and I heard some amazing stories.

16 Voices

I decided to approach these stories systematically through extensive qualitative interviews with students and some of their parents. I identified 16 students with disabilities that had become obvious from birth through 1st grade and collected their stories in my book How Did You Get Here?: Students with Disabilities and Their Journeys to Harvard. The students' challenges included deafness, muscular dystrophy, blindness, dyslexia, and psychiatric disability; one student was deaf and blind. One, Laura Schifter, who has dyslexia and is now on the faculty at Harvard, cowrote the book with me. Another, Wendy Harbour, who is deaf, wrote the afterword.

I chose this group because their disabilities had affected their K–12 educations, and I felt their stories would be informative to teachers and administrators. Although no two students had the same story, all of them experienced both high and low points in their schooling. Strong themes emerged as I heard these stories—themes important for educators to consider.

I discovered the crucial thing that made these young people's achievements possible: They developed strategies that enabled them to be highly successful in school. Just as important, they usually developed these strategies with the help of teachers, therapists, and parents. Most told stories of highly influential educators who changed their lives. I present here some of their insights.

"He Saw Something in Me"

Most of these students had a metacognitive understanding of their disability by the middle grades. They understood how they learned and what tools and skills they needed to be successful. But here's what's most important: They didn't accept that their disability should limit their potential to learn. In general, children at this age cannot develop such insights on their own; educators and parents had clearly assisted them in this important process.

Brian, a student from a low-income background who attended inner-city schools, talked reverently about his teachers. He had great difficulty learning to read and eventually was placed in special education. There he was taught by a teacher who helped him learn to read, but also insisted that Brian be included in general education classes. Brian told me, "I had teachers who believed in me!" and that three specific high school teachers "had the most profound effect on me. They were the best teachers I ever had."

Certain teachers allowed Brian to enter school early to compose papers on a computer because he didn't have one at home. Brian noted that many of his teachers who had attended prestigious historical black universities were important role models for him. Brian went on to the state university on a full scholarship and is now working on his PhD.

Alex, a deaf student who is currently in law school, received a cochlear implant when he was eight. An impressive speech therapist entered Alex's life as he began to learn spoken English and transitioned from a school for the deaf to a mainstream school. Alex explained:

My speech therapist is probably one of the reasons I was intellectually motivated and part of the reason for where I am today. . . He intellectually challenged me with book recommendations. The sessions weren't just about speech therapy and learning the spoken English language, they were about general knowledge acquisition, as my speech therapist recognized my intellectual drive and nourished it.

Mary, whose vision deteriorated over time, spoke of the influence of her middle school math teacher: "He saw something in me. … He was going to the principal's office saying, 'this girl's got it. This girl's got something to look out for.' " This teacher would have Mary solve problems in front of the class, "because we are going to see how her mind works." This experience, which Mary relished, helped her become popular with the academically advanced students in the school, which was very important to her progress. Mary is now a lobbyist for an education nonprofit in Washington, D.C.

"She Helped Me Think, 'How Do I Get Around It?' "

Once these young people had developed confidence that their disabilities shouldn't limit their intellectual potential, strategies that enabled them to fully access a challenging curriculum were central to their success. After all, although most had received specialized interventions that minimized the impact of their disabilities, their disabilities didn't go away. These challenges continued to affect their ability to access the curriculum.

Justin couldn't read in his early elementary years and had difficulty sitting still. After repeating 3rd grade, he attended a special school for students with dyslexia for two years. Not only did teachers there teach him to read, but they also helped him develop tools for learning:

I understood what I needed to be successful as a learner, and I had a pretty solid foundation. I knew how to extract important meaning from a text as well as how to effectively organize my writing. … These things were explicitly taught … As I moved up to high school, these strategies helped keep me on track. In many ways, I was better at tackling and solving problems than most kids.

Justin is now a successful principal who credits the insights he acquired through coping with his own learning differences with helping him become a school leader.

Nicole faced both learning and emotional challenges, culminating in a suicide attempt in high school. She was placed in a therapeutic school, where she was diagnosed with dyslexia. Teachers and therapists helped her develop strategies around both her reading difficulties and her anxiety. As Nicole said of her therapist,

She helped me look at situations with [the approach] "How do I get around it?" That was the school [that was] like, "There's more than one way to skin a cat."

As Nicole's professor, I was constantly impressed with how well she handled her anxiety disorder. Those coping skills served her well as she earned her doctorate.

From "Badass" to Researcher

Some students self-accommodated. Eric had problems learning how to read in the primary grades and was diagnosed with dyslexia. However, his parents resisted special education because it meant he would be placed in a segregated class. Eric continued to struggle academically and behaviorally. "In middle school," he recalled, "the strategy was to be a badass. If I'm not going to do well in the classroom, then I'd better be able to hold my own on the playground." Fortunately for Eric, his teachers recognized his talent for music and math.

In high school, Eric developed a desire to read for pleasure, but "just couldn't get through the damn books." He started hanging out with intellectually oriented kids and would engage them in deep discussions of the books he was pushing through. This enabled him to shine in class.

Eric went on to a unique liberal arts college that allowed him to design an individualized program. The skill he learned of connecting with peers who were more facile in reading served him fairly well. When Eric started graduate school at Harvard, he struggled with the reading and writing load. Through his course work, he gained a clearer understanding of his dyslexia and developed new insights into his issues. Eventually, he became somewhat comfortable identifying himself as a dyslexic and seeking the accommodations he needs to be successful.

Eric is now a senior researcher at a large research firm. When I consider his story, I'm struck by how tenuous his success was. He said his middle school friends are mostly in prison now. How many kids with similar issues end up like those friends because they don't get the supports they need when they're young? It's up to us to make sure kids get what they need as early as possible.

"I Can't Imagine Doing This Without Technology"

Another theme was how the right technology can be a turning point for students with disabilities. For instance, at Harvard, Eric started using text-to-speech technology for all his reading assignments. He continues to use this in his work today, noting, "Mostly it means that I am going to have digitized text. … I will have my computer, plug in my headphones, I can listen to it, and we will be all set." He also dictates papers and reports into his computer. He told me,

I can't imagine … being a doctoral student, doing research, and doing the level and volume of writing that I do without technology. I mean, it's everything—every sort of idea I interact with and every piece of work I do. Certainly there's this understanding of myself as a learner, but there's also the way technology has advanced. The things I use today weren't available in the mid '90s.

Most of these students were in elementary school as the digital revolution unfolded. Unlike Eric, they were connected to technology earlier in their schooling. Kevin, who has significant disabilities due to cerebral palsy, spoke about how a teacher "introduced me to my first computer, which would ultimately transform my life because it would allow me to express myself." When I interviewed Amy—a young woman with very low vision, which declined while she was in school—she mentioned technology so often that I felt I was getting an inside history of technology for the blind and vision-impaired. Amy noted how receiving her first laptop (paid for by the school) in 7th grade and using the programs ZoomText with speech and OpenBook made a huge difference for her.

Nick lost his vision in elementary school as a result of surgery to treat cancer. I was so impressed by how well Nick's strategies allowed him to access class materials (and the world in general—Nick has hiked all over the planet) that I asked him to demonstrate the way he uses technology to my class. Nick uses JAWS, a software program designed for blind people, to help him organize his course material in files that he can easily access. He employs a GPS in connection with his cane to navigate the world.

Blind students, he notes, "don't have the luxury of being able to quickly scan through a stack of papers or spot an object we have placed out of the way." Nick used JAWS in the beginning of the semester to create folders where he could store notes and readings for individual classes. He could access these materials "with just a few keystrokes: the first letter of the class, a few arrow presses to reach the correct week's folder, and then selecting the needed document." He used the same approach to organize his classroom materials when he was a middle school English teacher.

I asked Nick if he used the old "technology" of braille. He said braille was too slow and cumbersome for him to keep up the volume of reading he had to do as a graduate student. However, he added, "Reading braille is real reading for me! I'm not listening to another's voice but creating words and images for myself." The joy in Nick's voice rivaled my own joy in reading print—a joy we as educators hope to impart to all learners.

The Barrier of Attitudes

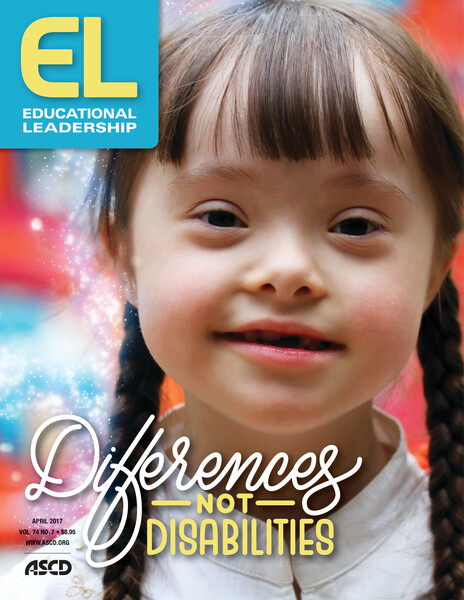

As I reflect on the important role that technology plays for most of these students, two conclusions come to mind. First, it's wonderful that old and new technologies are available to help people fully access education—and life. This issue of EL focuses on the question of moving from the notion of disabilities to the notion of differences. For many of these students, technology has effectively eliminated or diminished the impact of their disabilities to the point where they are no longer "disabled" in certain situations.

However, I'm concerned that in too many schools I visit, students who could benefit from these technologies aren't being given access to them. The cost of assistive technologies has gone down; some are now free. But I keep encountering the barrier of attitudes. For instance, I regularly meet educators who view access to text-to-speech technology as "not reading" or as giving kids an unfair advantage, even in schools where paraprofessional read to students.

I believe we, as educators, must encourage all students to be in text a great deal. Text is the most efficient means we have to communicate knowledge, develop vocabulary, and impart the wisdom of the ages to children, even for students who struggle the most with reading. All learners should experience the joy and benefits of reading. However, to achieve this goal for all students, we must encourage them to read through the means that are most efficient and effective for them.

Technology can be one way to accomplish this goal. This isn't to say that not all children should be taught to read well. They should. However, when young people have a disability that interferes with their ability to see or process written text fluently, we should give them an alternative that allows them to access text.

A Gift

Getting to know these impressive young people has been a great gift to me as a lifelong teacher and education leader. It's truly gratifying to see the progress we have made in the U.S. education system over the past 40-plus years as we extend more opportunities to students with disabilities. Work still needs to be done. But increasingly, we know what we need to do—and we have the tools we require—to let all students achieve their dreams.

Author's Note: All names of students are pseudonyms.

EL Online

For another success story, see the online article "What I've Learned as a Teacher with a Disability" by Alison Venter.