Every year, approximately one-third of U.S. public high school students don't graduate (Bridgeland, DiIulio, & Morison, 2006). Many of these students give up on school because they have borderline reading skills that make learning stressful and difficult. At any age, it's embarrassing for students to struggle and stumble over words while reading aloud. But for adolescents, embarrassment and repeated failure can become so painful that they feel their best recourse is to leave school. In a recent study, researchers found that teens with poor reading skills were more likely than competent readers to experience anxiety disorders, drop out of school, and even contemplate suicide (Daniel et al., 2006).

Even if they remain in school, the struggle takes a devastating emotional toll on at-risk readers—and their teachers. Many teachers with whom my colleagues and I work report that their at-risk readers are angry (the most common response), frustrated, lazy, or withdrawn. These teachers note that they spend 50 to 90 percent of class time dealing with these students' negative behaviors. At the end of the day, many teachers feel frustrated, sad, and burned out.

Teachers need powerful interventions that can propel low-skilled readers forward. In schools that use an approach I have developed called Reading Styles, we see interventions based on this approach do just that. We've watched teenagers with poor reading skills make substantial gains in a short period, engage in more voluntary reading, and show fewer disruptive behaviors.

Whole schools often take a leap in achievement. For example, after I.S. 206 Ann Mersereau Middle School in the Bronx adopted Reading Styles interventions schoolwide in 2007, the school markedly improved student achievement. In 2006, Mersereau received a D rating and scored in the 12th percentile on New York City's Progress Report, which compares the city's schools that have similar populations on such measures as attendance and achievement. One year later, Mersereau had jumped to the 90th percentile and received an A rating. By 2009, the school performed at the 99th percentile. This kind of dramatic change happens because the assessments and interventions associated with the Reading Styles Program—which are used extensively in Reading Styles model schools and labs—take into account struggling adolescents' natural learning strengths, interests, and needs. But teachers can put some of these strategies into practice for teens with reading difficulties regardless of whether a school formally signs on with Reading Styles and receives its training and materials.

Four key interventions make up the core of the approach.

Intervention 1. Match Students' Reading Styles

"Why did it take them so long to figure this out?" —Damon, age 14

Each person has a special learning style for reading. Figuring out what kinds of conditions tap into a student's natural reading style, rather than run counter to it, is half the battle.

Many of today's reading programs are highly analytic and require sedentary behaviors like listening or completing worksheets. Yet, at-risk readers of all ages tend to be global, tactile/kinesthetic learners (Carbo, 2009a; Dunn, Griggs, Olson, Gorman, & Beasley, 1995). To teach global learners well, meaning is the key. Global students must be deeply interested in what they are reading to do their best. They need high-interest, challenging stories and books and holistic reading methods, and they respond well to learning reading skills through game formats. They also tend to have a high need for movement and benefit from opportunities to work with peers, choose what they read, and read in soft light. These strategies have been especially beneficial for boys (Newkirk, 2003; Thies, 1999/2000).

The Reading Styles approach includes an assessment of reading styles (The Reading Style Inventory) that measures strengths, weaknesses, and preferences, particularly in two areas: (1) a reader's tendency to be more global or analytic in processing information, and (2) a reader's strengths or deficits in auditory, visual, tactile, and kinesthetic perception.

It's important to identify the reading styles of adolescents with poor reading skills and to share that information with each student. Information on the Reading Style Inventory, what it measures, and how to use it is available at the Reading Styles Web site (www.nrsi.com). Intervention 2. Record Challenging Stories.

"It was like a miracle. I was laughing because I read 100 percent better." —Jaycee, age 12

The most powerful intervention is something any teacher can use: a special method of recording short stories that enables students to read stories above their reading level with improved comprehension and fluency. Students listen to stories that are prerecorded at a slightly slower than normal pace with short, natural phrases and strong expression (Carbo, 1978; 2009b). As a struggling reader listens to the recorded story while looking at the text, the slow pace allows the reader to synchronize the spoken and printed words. Students can visually track the words and connect them to the words on the recording. The natural, chunked phrasing and expressiveness increase comprehension.

Teachers in the lower elementary grades often record stories themselves using this method, but this becomes difficult in the upper grades. By middle school, there is a wide range of student reading levels within one class, and students need to have many different story choices at and above their reading level to stay motivated; recording that many stories is time-consuming and difficult. Some schools train parent volunteers to record stories. At the Reading Styles Web site, teachers can listen to and print out prerecorded stories and purchase stories at different reading levels at a low cost.

To master a challenging story, most students need to listen to a recording at least two or three times. The student then reads back a portion of the story to the teacher, summarizes the story, and answers a few comprehension questions. To reduce stress, students should be allowed to do these readbacks when they feel ready.

Intervention 3. Provide Reading Choices

"Can I read more? I never read a whole page to anyone before."—Sal, age 17

Older at-risk readers have a slim chance of reading anything that interests them in school because a large gap exists between the reading materials most teens prefer and the books generally offered in class. Most 6th graders, for example, enjoy reading comic books, popular magazines, series books, and funny or scary stories—a far cry from assigned texts (Worthy, Moorman, & Turner, 1999). In our work with adolescents, the highest reading gains have occurred when a wide range of high-interest, specially recorded stories are available and when students are allowed many reading choices.

It also speeds progress to stretch students into higher-level stories. Special education teacher Linda Queiruga had great success using the recording method with 33 10th graders at Canyon del Oro High School in Tucson. Queiruga recorded 200 high-interest stories ranging from 3rd-grade to 9th-grade reading levels—about six years higher than her students' average reading level—and labeled each envelope containing a story and its audiotapes with the title and reading level of the text. She privately told students their reading level and gave them these simple requirements: Students had to listen to and track a story that was at least one year higher than their reading level, read parts of the story back to Queiruga with no more than three errors, and summarize the story.

Most students read about two recorded stories each week (Some students needed more repetitions because they chose such high-level stories, so they read fewer stories.) In four months, students averaged a reading-level gain of 2.2 years, with the highest gains of three and four years made by boys (Queiruga, 1992).

Intervention 4. Provide Helpful Physical Conditions

"What do I have to do to get into this classroom?"—Eduardo, age 14

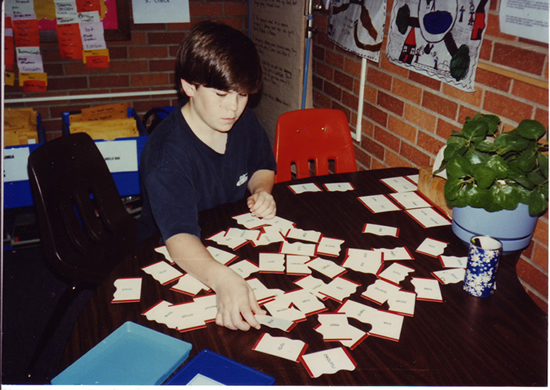

Because many at-risk readers are tactile/kinesthetic learners with high mobility needs, differentiating instruction for these students includes providing informal reading areas (containing rugs, pillows, or soft furniture); soft lighting (achieved by removing overhead light bulbs or using lamps); and reading games (especially those that use the vocabulary and context of the story). Such additions enable students with high mobility needs to relax, concentrate on learning, and associate reading with pleasure.

Many struggling adolescent readers respond well to reading games that reinforce skills.

<ATTRIB>Photo courtesy of Marie Carbo.</ATTRIB>

Reducing the light in a room can also help learners who report that when they look at text, words and letters seem to double, reverse, shake, disappear, or slide off the page. Bright light can increase this perceived letter movement. If possible, turn off half the lights in a room and allow students who have difficulty working in bright light to work on the dimmer side.

Colored overlays or tinted eyeglasses can also help some students who report these symptoms (O'Connor, Sofo, Kendall, & Olsen, 1990). Different colors help different people, and it may take many tries to find the best color for a particular student. (See www.seeitright.com for more information on using colored overlays.) Other accommodations for students who experience visual problems when they look at text include using dark-colored markers on whiteboards and duplicating assignments and lists on colored paper. Creating Readers, Not Statistics

Interventions like these help adolescent at-risk readers make large gains in reading, which helps protect them against dropping out. Such protection is crucial because the U.S. high school dropout rate has serious consequences both for teenagers who quit school and for society. High school dropouts earn significantly less money throughout their lives than do high school and college graduates. They are much more likely to be unemployed, receive public assistance, become single parents, or end up incarcerated. Researchers estimate that each young person who drops out of school and gets involved with drugs or crime costs the United States a staggering $1.7 to $2.3 million (Bridgeland et al., 2006).

If teachers can help at-risk readers enjoy reading and believe in themselves and their ability to learn, each of these kids can become a reader rather than a statistic.