I've been in this system for 30 years. I was never expected to make my own decisions about anything related to curriculum. I was handed the basal reader and worksheets and told to follow the directions. Now, I have to make decisions about which outcomes I want the children to develop, which pieces of literature they should read, and which assessment tools are best. It's hard, it's going to take me a while, and it's also very exciting!”—Ann Tanona, Classroom Teacher

Prompted by an attempt to integrate whole language teaching into all of their elementary classrooms, teachers in the Westwood Public Schools in Westwood, Massachusetts, have been assuming a more central role in choosing and creating curriculum. In fact, the construction of curriculum by teachers—within their classrooms and within the political context of their school systems—is a goal in many curriculum movements associated with the “constructivist philosophy” (Lampert 1988).

Whole language is just one example of curriculum reform aimed at increasing teacher involvement in the decision-making process. Such curriculum reform movements, in conjunction with structural reforms such as site-based management, are giving teachers an opportunity to examine and redefine their roles both inside and outside the classroom.

Although the whole language movement has sparked controversy, it has established professional dialogue about the purpose of literacy education, compelled practitioners to critically examine the existing curriculum, and increased the diversity of instructional strategies available to teachers. As a result, teachers are being invested with new authority.

The new authority of teachers for curricular decisions, however, can create tension over what should be centralized or decentralized decisions. Who should decide what should be learned, how it should be learned, and how it should be assessed? While decisions about what and how we want students to learn are best made by professionals within the local school system, both administrators and teachers must be clear about the purpose and focus of decision making. Teachers can and should be trusted to make decisions that are based upon the individual needs of learners in the classroom, because the idiosyncratic nature of learning requires both flexibility and responsiveness (Huberman 1983, McDonald 1992). In contrast, the collective nature of a school system requires uniformity and consensus around educational outcomes. Herein lies the potential source of conflict.

Despite a growing body of literature that suggests that classroom teachers “will require substantial autonomy to make appropriate instructional decisions” (Smylie and Conyers 1991), new roles for teachers in curriculum development conflict with traditional expectations. The perception of teaching as isolated work persists (Lortie 1975, Little 1990), while on the other hand, some scholars point to the “de-skilling of teachers” (Shannon 1989) and an acquired “habit of mindlessness” (Meier 1992) that have contributed to overreliance on instructional materials and an inability to make instructional decisions. In addition, the political concern over educational quality, the increased pressure for accountability, and an emphasis on the need for national standards give teachers mixed messages regarding their level of authority and the extent of their autonomy.

Until the parameters of teacher autonomy are defined, new roles for teachers cannot be realized. Although we believe that teachers should be making curricular decisions, we recognize that they must be supported in this process by administrators. Because the process of constructing curriculum involves both individual flexibility and collective uniformity on the part of teachers, new roles can only be defined through meaningful inquiry about classroom practice and curriculum. Our observations suggest that a new definition of autonomy needs to include both collective and individual levels of teacher involvement in decision making.

The Curriculum Inquiry Model

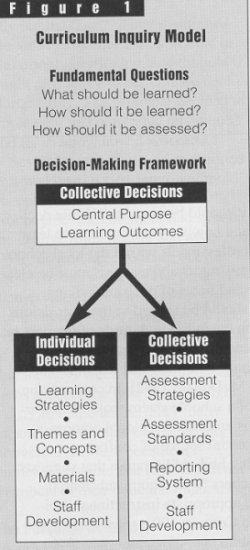

As a framework for outlining the parameters of teacher choice and for focusing decision making by teachers, we have used the Curriculum Inquiry Model in several school systems (fig. 1). Integrating elements of educational practice that are often dealt with in isolation—instruction, curriculum, assessment, and staff development—the model is unified around three fundamental questions about learning: What should be learned? How should it be learned? and How should it be assessed? Three clusters of questions move decision makers through the model. Two clusters focus on issues to be decided collectively, and one cluster outlines decisions to be made by individual teachers within their classrooms.

Figure 1. Curriculum Inquiry Model

Westwood Public Schools provide one example of a school system attempting to redefine teachers' roles and decision-making parameters using the Curriculum Inquiry Model. The whole language philosophy they have been implementing provides a rich context for “reinventing teaching” (Meier 1992), and the process of creating curriculum in Westwood was facilitated by using the model to encourage teachers to ask the “right” questions.

Collective Decisions

The first cluster of questions that must be answered include: What is the central purpose of the school system, and What are the learning outcomes that we are striving toward? These questions require collective decisions. As the faculty of the Westwood Public Schools began to implement a whole language philosophy in the elementary grades, they built upon a systemwide purpose that included the goal of “developing linguistic literacy.” A faculty committee identified learning outcomes to achieve that goal.

For example, by the end of 2nd grade, a student will differentiate between fiction and nonfiction texts, integrate story structure in writing, and use phonetic and visual elements in spelling. A student leaving 5th grade should recognize and identify an author's style, attempt to write and respond in a variety of genres, and use conventions of language appropriately.

By establishing exit outcomes (Spady 1988) at the 2nd and 5th grade levels, the committee came to consensus around shared goals for literacy education in the elementary grades (Westwood Public Schools 1992c). While the outcomes provide a uniform purpose and focus for curriculum construction, they are stated in such a way as to encourage individual interpretation and innovation on the part of teachers (Pahl and Monson 1992). In fact, their global orientation virtually demands individual decisions regarding their impact on classroom practice.

Once outcomes were established, committees began to address the second cluster of questions: What assessment strategies and standards should be used to monitor student progress toward these outcomes? What reporting system should be used? and What kinds of staff development will support implementation? Included among the assessment strategies developed was a literacy checklist, a tool to keep track of the ways in which students demonstrate growing competence in the learning outcomes (Westwood Public Schools 1992b). In addition to the checklist, teachers began developing assessment tools such as miscue analysis (Watson and Henson 1991), retelling (Brown and Cambourne 1987), literature circle observation (Watson 1990), and analytic trait assessment (Spandel and Stiggins 1990).

At the same time, a committee of teachers established a reporting system (Westwood Public Schools 1992a) aligned with the learning outcomes. The reporting system is based upon both a revised report card and a parent conference structure for sharing evidence of student progress.

Currently, teachers are meeting in grade level groups to identify, by consensus, minimum and exemplary performance standards at each level. Driving the discussions is an assumption that agreement around a continuum of performance standards would later promote communication and curriculum articulation among grade levels. That is, teachers in different grades would see connections among their individual attempts to promote the same learning outcome in a developmentally appropriate way.

Recognizing the tremendous impact these changes would have on classroom teachers, the district devoted two half-days every month and two additional full days every year to staff development, planned with input from teachers. Staff development primarily focused on awareness and skill development related to whole language curriculum construction.

Individual Decisions

Working within the framework of the collective decisions, Westwood teachers then had to construct a literacy curriculum for their own classrooms (Sumara and Walker 1991). Decisions made by individual teachers revolved around the questions of which learning strategies, themes, concepts, and materials would foster the development of the defined outcomes. Teachers also needed to determine how to access staff development.

Staff development was critical in helping teachers begin to make individual curricular decisions. Westwood initially concentrated on supporting teachers in developing a knowledge base for making informed decisions about what should be learned and how. Teachers selected core literature pieces and purchased multiple copies of selected titles at each grade level. They practiced whole language learning strategies such as shared reading, literature circles, response journals, and story mapping to enhance their instructional repertoires. They identified core themes and concepts appropriate to the level of their students. This knowledge base put teachers in a stronger position to construct curriculum.

Efforts have now shifted to supporting teachers in constructing curriculum. Within the framework provided by the learning outcomes, teachers are making individual decisions based upon the contexts of their own classrooms. As a result, the curriculum is being realized in a unique way in each classroom with each teacher choosing a way to address the outcomes. Teachers are also identifying their own personal professional development needs so that staff development sessions can be planned around them.

An Emerging View

Although we involved teachers in creating curriculum in the context of literacy education, we can draw parallels to efforts to design mathematics curriculum based upon the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics standards (1987). Both of these movements conceptualize curriculum development in a manner consistent with the constructivist philosophy (Lampert 1988), requiring teachers to play an active role in curriculum construction.

As a result of our attempts to implement the Curriculum Inquiry Model in Westwood and other settings, we have come to recognize that the process is fraught with uncertainties and ambiguities. Many questions remain unanswered: How much diversity in classroom practice can a school system tolerate? At what point does uniformity at the school system level inhibit the individual creativity of classroom teachers? Through curriculum inquiry, we hope that practitioners will discover a coherent set of questions through which to construct a curriculum crafted by both the collective and individual actions of teachers. With collective decision making determining the curriculum of the school system, the informed decisions of individual teachers can shape instruction in the classroom.