One thing we've learned over the course of the pandemic is that relationships are central. Humans are wired for social engagement. Now more than ever, schools need to create cultures of belonging in which every member of the school community is valued—where their voice can be heard, where they are invited to the table for problem solving and innovative thinking, where their differences are seen as strengths, and where there is a dedication to their overall well-being.

As consultants who have helped many schools and districts infuse thinking dispositions we call the Habits of Mind into their school's culture and practices, we've witnessed the profound transformation of schools through this approach. The Habits of Mind can provide a crucial element in building a culture of efficacy in schools and communities.

What Are the Habits of Mind?

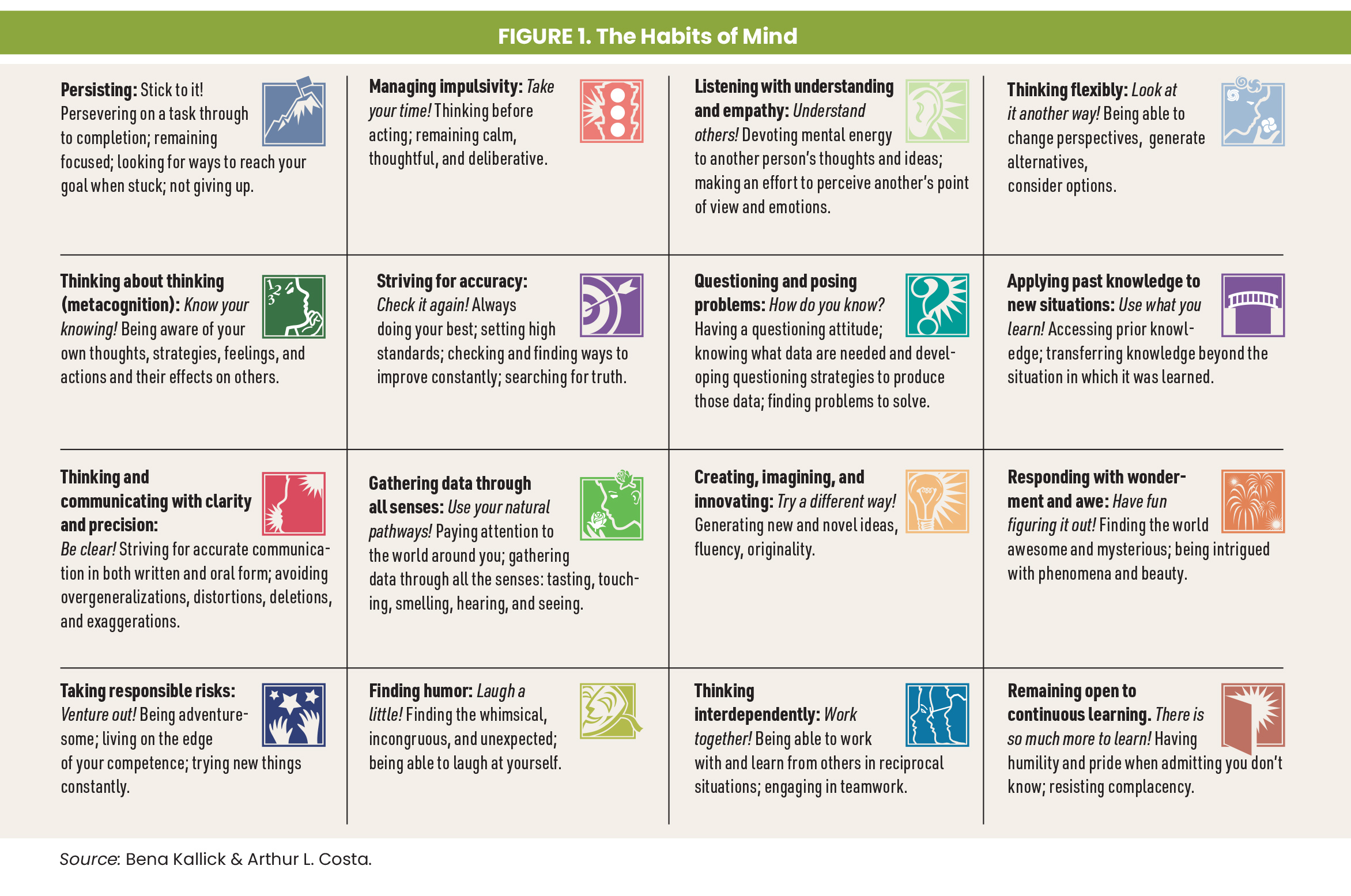

The Habits of Mind are 16 thinking dispositions at the core of social, emotional, and cognitive behaviors (see fig. 1). Two of us, Art Costa and Bena Kallick (2008), derived these habits from studies of how "successful" people from all walks of life respond intelligently and empathically when confronted with problem situations, conflicts, and uncertainties for which the resolutions aren't immediately apparent.

Nurturing these Habits of Mind throughout a school develops the entire school community's capacity to recognize and apply dispositional thinking to the curriculum and the unpredictable challenges and opportunities a school faces. In cultures of efficacy, all members confront problematic situations by learning to employ one or more of these habits, asking themselves, "What is the most intelligent thing I can do right now?" This question is not only valuable for students, it has proven to be valuable for the entire school community as a school's culture grows.

Seven Key Factors

As they integrate this question into their work, schools can develop a culture of efficacy grounded in the Habits of Mind—a culture in which educators can see and build on evidence of their ability to create change. We've found that seven key factors contribute to this culture: common vocabulary, social norms, de-privatized practice, shared indicators of growth, parents and community as partners, a shared vision of graduates, and leadership. When these factors work in concert with one another, they create a condition neuroscience terms "attention density." This means that "density" of experience—when one focuses long enough, intensely enough, and often enough on an idea or behavior—can change neural pathways and brain circuitry (Rock & Swartz, 2006).

Let's look at each of these factors in turn.

1. Common Vocabulary

The Habits of Mind provide a common language that anchors communication throughout the school community. Whether in talk between students, parents, administrators, members of the community, or each other, this vocabulary provides description and recognition of the challenges, aspirations, celebrations, and ideas that pervade daily work in schools. As students hear the language and link terms like persisting and questioning and posing problems with the observed behaviors of the adults, they soon realize "this is how we do things around here."

2. Social Norms

Social norms are informal understandings that govern the behavior of members of an organization—rules that prescribe what people should and shouldn't do given their social surroundings. Educators turn to norms when facing complex problems, such as when (based on parent feedback) school report cards don't accurately capture students' classroom performance. Imagine a principal opens a faculty meeting with an agenda listing this problem and some questions that have been raised. After welcoming the staff, she says, "We're aware that we need to change our report card. Let's generate some options based on the feedback we have received from parents. Which Habits of Mind will help us work together today?" The staff reflects on which habits will best serve them as they approach the redesign of a report card and commit to behaviors like:

"We'll listen with understanding and empathy to each other's point of view."

"We will think flexibly and generate many ways of solving these problems."

"Let's remember to find a little humor and laugh together!"

Now, more than ever, schools need to create a culture of belonging in which every member of the school community is valued and invited into problem solving.

3. De-Privatized Practice

Some school staff seldom interact with teachers from other departments. In schools that center on the Habits of Mind, however, staff members make their practice public to one another because they share a common vision of their graduates. Each subject area group finds ways of building the habits into their curriculum by providing settings in which students can transfer and apply relevant habits. Students create, innovate, and imagine, for example, not only in art class, but also in the robotics lab.

4. Shared Indicators of Growth

Because staff members in schools drawing on the Habits of Mind share a commitment to fostering students' progress in these ways, they often dialogue about indicators they observe that show students growing in the habits (Kallick & Zmuda, 2017). We've seen teachers describe indicators like:

The student body president advocating for the use of listening with understanding and empathy to each other's point of view as he conducted the student council meeting.

At Kittredge School in San Francisco, 8th graders adopted learning buddies from kindergarten and 1st grade. The 8th and 1st graders read stories together and found examples of the Habits of Mind. For instance, as one buddy pair read Charlotte's Web they discussed how the pig needed to manage its impulsivity.

When a student named John was in 3rd grade, he complained that there was too much emphasis on the Habits of Mind. No matter where he turned, he said, they reappeared. But as a 6th grader, this same student advocated for listening with empathy in a school project that involved visiting with homeless people to better understand their problems.

We've had educators and school personnel tell us that their whole school community pays attention to how they use the habits in their meetings. When staff members, parents, and students collectively embrace the Habits of Mind and work together to model, recognize, and reinforce them, they begin to realize their positive effects. They have a feeling of confidence in themselves, belief in their mission, and value of their actions—what Bandura defined as "collective efficacy" (1977, p. 477). John Hattie positioned collective efficacy at the top of his list of factors that influence student achievement (2016).

5. Parents and Community as Partners

It's much more likely that students will learn and practice the Habits of Mind if they witness their parents and community members dialoguing about and exhibiting these habits as well. Students should hear adults describe how they need to listen, pose questions, think creatively, and persist in their work—and how they see the habits in action. For instance:

Students in a secondary school in Brisbane, Australia, invited business leaders from the community to school so they could share the Habits of Mind with these leaders and determine whether they valued their employees using any of the habits in performing their work.

One parent shared this insight: "We talk about the Habits of Mind as a family, and I share them with friends because I find them to be pertinent and applicable in many situations. I love how the Habits of Mind reinforce and emphasize all of the characteristics that we value so highly."

Another parent commented, "After I made some cookies, I told Zachary he had to wait until after dinner to have one, to which he replied, 'I am managing my impulsivity for sure!'"

Students in Kettle Moraine, Wisconsin, discussed these powerful habits with local professionals. The town's Emergency Medical Services team identified that finding humor was essential to dealing with the enormous stress of their job.

6. A Shared Vision of Graduates

Imagine a teacher writing a letter of recommendation for a graduating student applying for college or a job. The Habits of Mind encompass attributes that employers welcome, such as: persistent, collaborative, precise, eager learner, or flexible thinker. When school staff and parents agree on the dispositions desired for graduates—and for teachers and administrators—they know what they're striving to, collectively, instill.

7. Well-Focused Leadership

The greatest power leaders have is that they can influence the narrative of a school. If the narrative focuses on test scores, current educational fads, or compliance to procedures and bus schedules, then that's what students and others involved will perceive as important about learning. In such schools, students learn to get to class on time, raise their hand when they wish to speak or ask a question, and listen to the teacher. Instead, if the narrative focuses on becoming aware of and managing thinking processes—such as what it means to be an empathetic listener or what alternative strategies might be generated to solve problems—then teachers and students begin to perceive learning in a different way: They will believe learning involves responding intelligently to challenges, having strategies to comprehend and tackle complex problems, and viewing setbacks as opportunities for learning (Donohoo, Hattie, & Eells, 2018).

Why Such a Culture Succeeds

The interplay of these seven key factors creates a culture of efficacy in which the Habits of Mind define the behaviors associated with the school or district culture, so there is a "density" of repetitions and recognitions of these positive behaviors. As students progress through the elementary grades or encounter various subject matters in high school, there is a recurring focus on the Habits of Mind. No matter where they turn—whether it be in a social studies class, a science lab, or on the football field, whether in kindergarten or any other grade level—their teachers invite them to focus on one or more of the habits as they engage with the content.

In addition, there may be signs and posters throughout the school and classrooms reminding the staff and students about the value of these 16 habits. Some schools recognize students with awards, badges, or bracelets for their performance of one or more habits. We've seen that the more students focus on and grapple with the habits, the more those dispositions become internalized in their hearts, minds, and behaviors.

The success of a culture of efficacy drawing on the Habits of Mind lies in the critical nature of collaboration and the strength of all community members believing in and fostering these habits (Tabor, 2019). Together, administrators, faculty, parents, and students can achieve magnificent and sustainable outcomes.

Early Childhood Success

Read Arthur L. Costa and Bena Kallick's 2019 book.