The idea of preparing students for the "real world" feels much like aiming at a moving target. Over the last few years, the workplace, like school itself, has experienced change in unanticipated and disruptive ways. Many trends, such as a growth in the leisure and hospitality industry, came to a screeching halt while others, such as the demand for remote work, gained momentum (OECD, 2021). One thing that has remained consistent is this: the world of work demands its employees possess increasing degrees of savvy in working collaboratively.

Even before the pandemic, the collaborative demands of the workplace were steadily on the rise. As more and more routine jobs such as factory work became automated, the occupations that remained—and the new jobs that emerged—required employees to thrive in social and collaborative skills (Deming, 2017; National Association of Colleges and Employers [NACE], 2018, 2019).

And even during the extreme upheaval of COVID-19, collaboration remained one of the most highly sought-after qualities in the marketplace. In fact, NACE's Job Outlook Report cited "teamwork" as one of the top three assets employers are seeking, along with problem-solving and analytical/quantitative skills, for the years 2021 and 2022 (Gray, 2021).

The Pandemic Effect

Despite the value collaboration holds in the workplace, schools have—understandably—shifted emphasis to more self-sufficient, self-contained methods of operating. When schools moved to remote learning, collaboration was one of the first things to go. According to a national survey, when learning moved online, 65 percent of teachers indicated they decreased the amount of group or partner work they used with their students (Schwartz, 2021). Simply getting students to log in to class was a challenge. Group work seemed impossible.

When students finally returned to the classroom, group work did not get much easier. Safety measures such as social distancing, plexiglass, and masks served as both physical and psychological barriers to teamwork. Even in schools where such rules were relaxed, legitimate fears remained, as did new patterns of individualized operating that seemed incredibly hard to undo.

Community building is a staple of any healthy classroom.

We are now experiencing some of the fallout of our retreat from collaboration as we try to help students work together again in face-to-face settings. Teachers and administrators are facing discipline issues on levels not seen before. Crystal Thorpe, principal of Fishers Junior High School in Indianapolis, surmises this is because students "missed out on social interaction at a crucial time in their development … [and] returned to school lacking skills like conflict management that they ordinarily learn from their peers" (Einhorn, 2022).

That may be the case, but over the long-term, our students will need to work together to solve increasingly complex problems—not just because the marketplace demands it, but because our world does. As we plan for student learning in the upcoming years, we must be mindful to plan for more of that learning to be collaborative. A hyper-focus on so-called "learning loss" can bring with it the danger of a hyper-focus on efficiency and result in isolated instructional models to make up for "lost time." Keeping our eye on long-term goals of equipping students to be (1) successful in their workplaces and (2) successful in shaping our world would suggest we keep in mind the African proverb, "If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together."

How Do We Go From Here?

How can we help students re-learn how to "go together"—to work collaboratively in a productive, peaceful, and even joyful way? The first step is to make sure we provide them with group-worthy tasks. Asking students to collaborate on completing a low-level worksheet or compiling a dry chapter summary can set the stage for conflict. Disagreements about minutia can easily erupt. And a boring task makes conflict that much more attractive. However, if the task is engaging and requires a diverse collection of thinkers to puzzle through it, the allure of the task becomes more compelling than the allure of conflict—and that appeal draws students into and through the work.

We can take additional cues about fostering effective collaboration from the corporate world. In 2016, Google conducted an intensive internal study to determine how to build the perfect team—one whose members operated in a highly productive, collaborative, and interdependent manner. They code-named their study "Project Aristotle" and concluded that successful teams share the following characteristics:

Psychological safety—Team members feel safe to take risks and be vulnerable.

Dependability—Team members get things done on time and meet a high bar for excellence.

Structure and clarity—Team members have clear roles, plans, and goals.

Meaning—Team members find the work they are doing personally meaningful.

Impact—Team members think the work they are doing matters and creates change.

Lessons from the Corporate World

While these findings were derived from the world of business, they are highly applicable to the world of school. Let's look at some practical ways to foster each of these characteristics in the context of K–12 classrooms.

Psychological Safety—Maslow taught us long ago that this is a necessary precursor for students to thrive. We know that students do not learn if they do not feel known, seen, safe, and accepted. Our chaotic new world will require a great deal more proactive and ongoing work to firmly establish such foundations of safety. We can accomplish this by building a healthy sense of community in classrooms and solidifying group norms through contracts.

Community building is a staple of any healthy classroom. Good teachers invest time at the beginning of the year getting to know their students and helping their students get to know one another by using strategies such as student surveys, attendance questions (such as, "Say your name and your favorite cereal"), BINGO cards, me-bags, identity crests, personal ecosystems, and the like. These are not "fluffy" activities; rather, they are opportunities for students to reduce stress, communicate their identity, find commonalities among class members, and set the stage for healthy academic collaborations. Good community building begins on day one but continues throughout the year; all good relationships require ongoing work and active maintenance to stay healthy.

Opportunities to Collaborate

Reserve time at the beginning and end of each class for groups to set goals for work time and to reflect on what's been accomplished.

Classroom contracts are a beginning-of-the-year (or semester) activity, although they should be revisited periodically throughout the year to make sure they still reflect the values of the class. Such collaborative agreements usually flow from a discussion or experience and capture student beliefs regarding what they will need from their classmates and their teacher to feel safe and free to take risks and to grow both socially and academically. A classroom contract usually spells out agreed upon classroom norms or behaviors and is signed by each member of the class. (If you have never created a classroom contract, check out this toolkit from Facing History and Ourselves.) Community building and classroom contracts have always been important, but today they serve as vital stability to counter the shifting sands in so many areas of our young people's lives. They cannot be neglected. And if this kind of foundation building becomes routine for our students, it will position them to replicate these conditions in their own future collaborative environments, whether that's in a university study group, the workplace, or their future family.

Dependability—Nothing can set a student off more quickly than a team member who is not "pulling their weight." An age-old cooperative learning struggle, this conflict has become exacerbated in the light of heightened intrapersonal and interpersonal tensions in schools. Clarity about what is expected from student work in terms of content, process, and quality is an important first step. These criteria can be communicated through rubrics or other evaluation tools (McTighe, Doubet, & Carbaugh, 2020). This keeps students on the same page as they do collaborative work, facilitating conversations around product review.

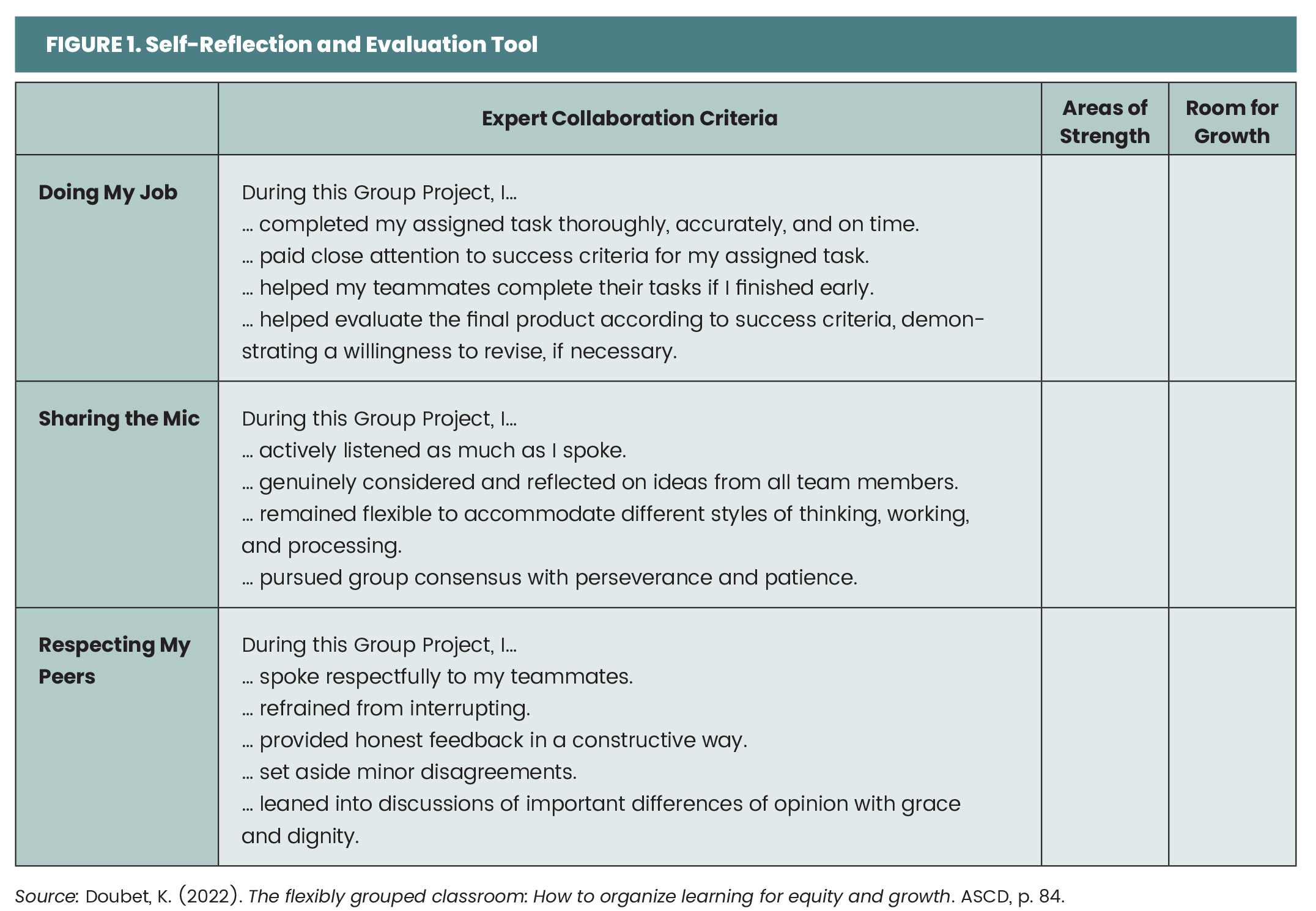

But rubrics can also guide students to review the social-emotional aspects of their collaborative work. Consider the self-reflection and evaluation tool I developed in Figure 1. This type of rubric can be used to facilitate the SEL skills of self-awareness, self-management, social-awareness, and relationships as defined by CASEL (2020). This helps reinforce what it means to be a dependable group member. Once students have engaged in self-reflection and become familiar with the criteria, they can move to a similar peer evaluation, in an anonymous and low-stakes format that is shared with the teacher. This helps the teacher monitor and guide future group interactions to facilitate success. Eventually, the teacher can summarize peer feedback and share overarching grows and glows with each team member.

Structure and Clarity—One benefit of the shift to online learning is that we got better with our structures for organizing, storing, and sharing work. Whether you use Google's suite of products or another learning management system, chances are your students know how to access, submit, and collaborate on materials. If they don't, it's worth the time to teach students these procedures. It's even worth making a few video tutorials they can play when they get stuck.

It's also a good idea to reserve time at the beginning and end of each class for groups to set goals for work time and reflect on what's been accomplished. Keeping a running list of each group's "to-do" items (also called a "scrum board") and moving them across columns from "not started" to "in progress" to "finished" helps both teacher and students stay on top of deadlines. Tools like Trello, Padlet, or Jamboard can facilitate this process digitally. The more familiar Google Forms tool provides a simple way for each group to regularly report what they've accomplished, what they plan to do next, and what they think they may need help with.

While these systems for structure and clarity appear administrative in nature, they are much more. They help students build the deeper life habits of goal setting, progress monitoring, and reflection—habits that undergird success, not just in the workplace, but in all other areas of life.

Meaning—Teachers know better than anyone that humans—especially our school-aged humans—need to find meaning in what they do to be motivated to persist and succeed. Giving students choices improves their motivation, and when project groups are comprised of members united by a common choice or area of interest, they are bonded by that choice (Doubet, 2022). But within those groups there needs to be choice as well, especially when it comes to group roles.

Nothing erodes group dynamics as fast as roles of unequal status (group enforcer vs. materials manager) being doled out to students like crowns and dunce caps. It is important that we make genuine efforts to discover what makes each student shine and then allow them to use that gift in service of the group. Not only does this affirm the worth of every student, it also helps students invest more deeply in the group task while further developing their talents—which ultimately makes the group's product better.

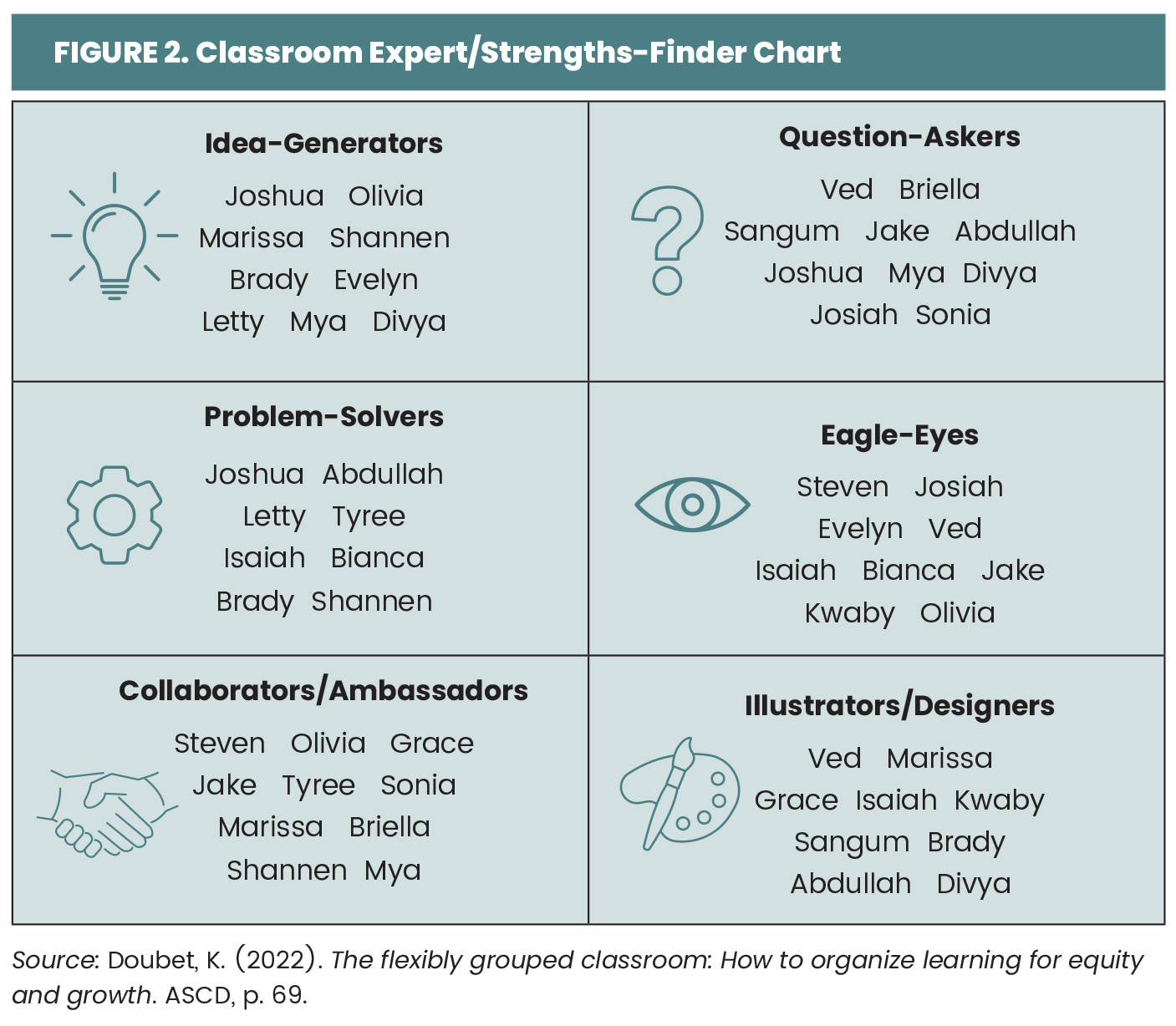

To make a classroom expert or "strengths-finder" chart, the teacher first determines what wide array of strengths will be needed to complete the meaningful tasks students will tackle. Those strengths (for instance, a detail person, someone good at persisting through problems, a conflict-solver, someone with an eye for design, and so on) are posted on a chart, and students sign their names under three areas they believe best represent their strengths (see Figure 2).

The teacher can reference this chart while creating groups to make sure someone with each strength important to the task is represented; alternatively she can ask students to select roles themselves, referencing the chart as they do so. This builds for students the life habit of not only recognizing and celebrating their own strengths but also noticing and affirming the gifts of others—including those who may typically go uncelebrated by too-narrow definitions of academic success (Doubet, 2022).

Impact—For impact, we simply need to revisit our discussion of "group-worthy" tasks. All the practical advice in the world will not save a collaborative endeavor if students are not pursuing work that captures their attention, curiosity, and intellect. Zaretta Hammond suggests asking students to solve real problems in the school or the community (Rebora, 2021). Such problems are certainly ubiquitous these days! Other options include asking students to create authentic products such as a public awareness campaign, use professional tools like Canva to design materials, or present their work to authentic audiences such as the school board (McTighe et al., 2020).

Group-worthy tasks capture the attention of students and keep them focused and productive. They set the stage so that there is reason to take risks, room for diverse and meaningful group roles, and purpose for reflection and evaluation. And they provide us with context to which students can connect or "stick" their learning.

Leveraging Students' Strengths

In her recent interview in this magazine, Zaretta Hammond pushes back against the idea of "learning loss" from the pandemic and focuses instead on the reality that

… students have unfinished learning. … Brains are learning machines. That is what they do. The reality is that all our students learned something during the pandemic. The problem is that we're not leveraging that. (Rebora, 2021, p. 17)

Now that sounds like a good place to start in our quest to reenergize collaboration. If we can leverage student curiosity with group-worthy tasks and leverage students' need for connection with safe, dependable, structured, and meaningful collaborative learning experiences, we can take vital steps toward gaining the academic and the social-emotional learning that remains unfinished. And we may find we make larger, more efficient steps in the academic realm if we pay as much attention to the SEL realm. That will get us closer to where we want our students to land, both in the near and the more distant future.

The Flexibly Grouped Classroom

Kristina Doubet's new book explores how flexible grouping enriches learning and disrupts rigid tracking.